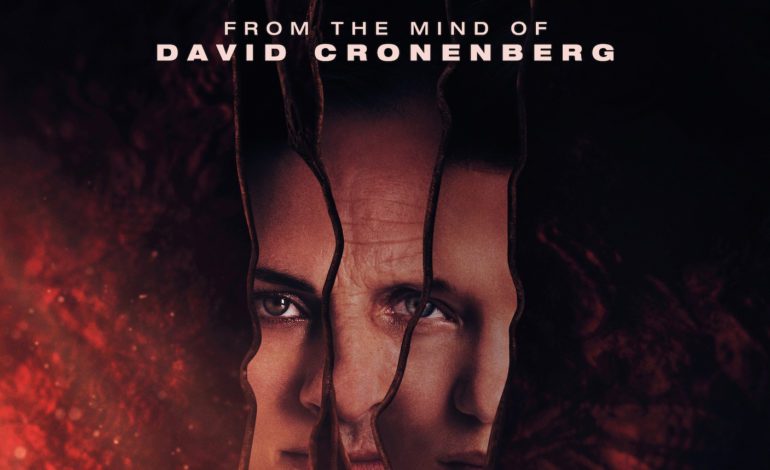

Human innovation, when thoroughly discussed, is a double edged sword. Many filmmakers like to use their art to explore what happens when humanity takes things too far. Should people genetically resurrect dinosaurs? The answer most films present to this and similar questions is usually no — even though it’s cool. It’s no surprise that David Cronenberg, the shocking-but-thoughtful auteur, would have thoughts on the matter. These are on display in his latest film, Crimes of the Future.

Crimes of the Future, fresh off a run at the 75th Cannes Film Festival, creates a world in which humans can no longer feel pain. As a result, surgery has become a popular activity, even to the point of high art. Saul (Viggo Mortensen) makes a living by growing new internal organs (another skill humans in this world have developed) and having them surgically removed by his artistic partner Caprese (Lea Seydoux).

Like most Cronenberg films, there are several elements of Crimes of the Future that are likely to shock the filmgoing public at large. If watching surgery or looking at internal organs makes you squeamish, this might be a difficult film to digest. However, the film is different from the typical body horror film. For one, Crimes of the Future isn’t scary. Cronenberg makes his admiration for the human body apparent both audibly and visually.

The film especially excels at creating a world that feels lived in and established, despite being fantastical in nature. Such a concept can take years and multiple films to establish (see any popular onscreen franchise for evidence), Cronenberg accomplishes this in under two hours, drawing from noir influences to do so. Actors in Cronenberg film often deliver the dialogue in a stiff manner, and Crimes of the Future is no exception. It may be that the viewer struggles over this barrier, but once it is conquered the spoken words fits in perfectly with the rest of the film.

Mortensen is a frequent Cronenberg collaborator, and does well with the material at hand. Seydoux, also excellent, has great chemistry with Mortensen, and together they create the heart of the film. Seydoux in particular seems to embody Cronenberg style. As the femme fatale of sorts, she dances through the performance with grace and candor. The supporting cast features Kristen Stewart, who makes an interesting choice with her character’s manner of speaking; but is nevertheless a good addition to the film.

Aesthetically, the film is unusual, creating a disturbing yet charming visual style. The production design is unique, as there is a prominently featured technology company that creates beds, eating chairs and surgery machines that are used by the characters. These machines are not pleasant to look at, but are nevertheless fascinating, embodying many of Cronenberg’s ruminations on the human body.

Despite the initial shock factor and the fact that Cronenberg himself predicted several walk-outs at Cannes, there is a lot to love in Crimes of the Future. The human body is simultaneously repulsive and beautiful. It is integral to everything we do and everything we are. Fiction allows us to push the parameters further than we could in actuality by presenting new ideas and rules for the body to follow. The film draws comparisons between human physicality and high art, asks the audience to define beauty, and to sit in their discomfort. It may not be an easy task, but it is a worthwhile one.

Rating: 4/5

Love, sex, art, loss, curiosity and evolution are all topics expertly handled in Crimes of the Future, but its treatise on the human body and the way things look are what makes the film stand out. With a body of work as large as Cronenberg’s, it is difficult to identify the outliers, but the film certainly works well as an embodiment of his frequented themes, ideas and signature style. For this reason alone, it is worth pursuing. However, Crimes of the Future has more to offer than that. And none of it requires surgery.