Welcome to Revisionist history, where we, unencumbered by the demands of studios and profit margins, try to imagine different and better versions of the movies that are out there. This is not a review; it is a full-spoiler discussion of what works and what doesn’t, particularly from a story/concept standpoint (i.e. unless there’s a particular tic that is distracting, it’s hard to account for a poor acting performance or other failure in execution alone other than to say, “Do better.” Which isn’t very interesting or helpful to anyone.)

This week, we’re revising Much Ado About Nothing.

Joss Whedon’s adaptation, or perhaps more accurately, staging of Much Ado About Nothing presents Revisionist History with a unique challenge. First off, this is one of the more interesting films I’ve seen in a while by simple virtue of the fact that it knows it’s a small film with a niche audience. It never tries to be anything more than that, and does a damn good job executing on exactly what it sets out to do. Second, though scholars better read on Shakespeare may debate the merits of the play itself, as Whedon and co. have adopted the text wholesale, there is little meaningful criticism that can be leveled at this movie alone when it comes to the story. Thus, unlike last week’s revision, this week we have two goals: explore a couple of the elements that make Much Ado About Nothing the particular (and peculiar) success that it is, and imagine in broad strokes what the film would be like if it were merely different than the version we are presented with.

(To skip the analysis and jump down to our revision, click here.)

In terms of execution, there are really two elements worth discussing. One, the modern setting (and its interplay with the original text), and two, the use of black and white filming. Let’s start with the first.

Stylistically, the film never amends the play’s text, so we still have princes and counts and governor’s daughters talking about Messina. But rather than the courts and costumes of the 16th century, we get suits and dresses in a Santa Monica mansion. This does make it a little strange when the film starts and we get very normal-looking people speaking Shakespearean English, but it’s a sensation that’s rooted more in shock than actual disconnect. On the contrary, it seems there is significance in the interplay between the modern setting and the classic text.

As much as I hate to focus overlong on the thematic material of any story (I find the journey is almost always more interesting than the destination), it’s hard to talk about the significance of the modern setting without diving headfirst into a little literary analysis. Much Ado About Nothing is very much about both the difficulty and ultimate importance of love, and true, committed love rather than the lusts of the hour. If you’ll notice, it’s only the villainous characters that we see being sexually intimate. Yes, in the opening scene we see Benedick leaving a woman’s bed, but his character arc is one of reformation. He is villainous and promiscuous at the beginning of the story. He is redeemed when he is caught up in true, self-sacrificing love. Look carefully – the other characters don’t condemn Benedick for his actions, but he is nonetheless separated by them. His opening scene is silent, isolated. Leonato and the others plot something better for him. The suggestion isn’t that sex is wrong, but that the sort of love that gives life rather than takes it is about more than mere sex.

So where does this fit into the discussion of the modern setting? On the most surface level, it can be seen as an indictment of modern, sex-drowned culture, and while this is valid, I think the effect goes deeper. In putting a bunch of (relatively) young, single people in a lavish house with lots of alcohol (there is hardly a scene without it) Whedon is re-creating the supposed ideal of the teen-sex comedy. But in Much Ado About Nothing, it isn’t debauchery to which the key players attentions are turned. It’s to the forming of lasting bonds of love, both fraternal and romantic. And if a little comedy ensues from their quazi-ridiculous plots, neither the characters nor the audience will mind.

Which brings us back to the use of the Shakespearean text. The balance between seriousness and ridiculousness is a hard line to toe. The placement of the play in a modern setting makes it more serious; the juxtaposition of modern setting with classical verbiage is comic. We’re reminded that this is something to have fun with. Can you imagine if these characters were speaking in modern English? We’d stop believing in the significance of the story because it would largely cease to be funny. Or if the movie were still set in 16th century Italy? It would appear complete farce. The twin forces of setting and dialogue actually work in concert, and we are given a story that is full of both humor and meaningful drama.

As for the decision to shoot in black and white, this further contributes this tonal balance. It connotes older, more dignified filmmaking. But at the same time the lack of color suggests that this is a world a half-step removed from our own, one where people might just show up at Leonato’s house and plot to get their companions hitched. We’re given license to fantasy without the story ever appearing wholly dismissible.

There are, of course, a lot of smaller but nonetheless key reasons why the film works as-is, but taking our cue from the movie itself, let’s balance this serious discussion with a little wonton fantasy. What would this movie be like, for example, if it was aimed at a wider audience?

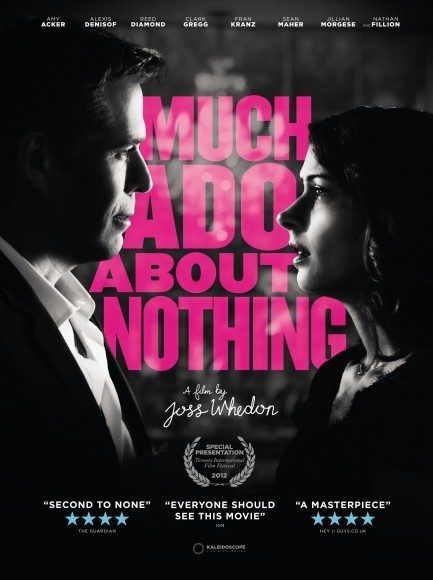

Let’s hold onto the black and white for a moment, but what if we introduced a little color here and there? The posters for this movie feature bright neon highlights against their grayscale background images. This is nowhere to be seen in the film, but it would have certainly been an aesthetically interesting touch. It’s not hard to imagine blotches of color cropping up here and there, perhaps even becoming the dramatic stylistic equivalent to Zach Snyder’s speed-up-slow-down editing of the action sequences in 300. Much Ado About Nothing would begin to take on a bit of a spectacle vibe, a circus-tent-like beckoning to experience the wonders contained within. There are elements of spectacle already in the film, such as Benedick’s attempts to escape detection while eavesdropping, Hero’s fainting at being accused of impropriety, and this shot of Claudio, which did make it into partial color, if only on the poster:

Throw in the party scene, which I found more visually compelling than Baz Luhrman’s equivalent in The Great Gastby, and you’ve got plenty of spectacle to start pitching as a movie full of wide eyed excitement.

Now that we’ve got the visual style, time to address the language. A couple years ago, I saw a brilliant adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors at the Court Theater in Chicago. The adaptation was written and directed Sean Graney and featured a hilarious mix of original dialogue and modern jargon. The script played off the combination and juxtaposition of the two for an experience that was both reverent of the source material and unafraid to try to pull in a more modern and potentially Shakespeare-apathetic audience. Granted, this worked in part because The Comedy of Errors is a much more openly slapstick play than Much Ado About Nothing, but I think a similar work could be done on the script of the latter. Moving in and out of the two can help clue audiences in to the meaning of some of the more obtuse constructions of the Shakespearean text. Much Ado About Nothing is a funny play on its own. Giving that humor an imaginative twist could be really compelling.

So there we have it. A visually and dialogically striking film that has a strong foundation in its source material but also makes significant departures from it. Again, this isn’t necessarily a better version of the film, just different. Whedon’s film is self-limiting, but it’s tailor-made for its audience. As much as anything, I’d just like to see our made up version for sake of comparison. That sounds fun. And if were’ for nothing else here in Revisionist History, we’re for having some fun.