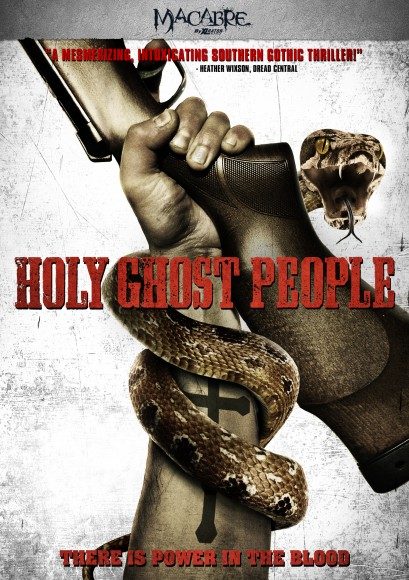

Here’s the thing about Holy Ghost People: it’s neither the slasher film you might expect from the filmmakers who frequently go by the name “The Butcher Brothers” nor the conversion story you might expect from a more spiritually-inspired reading of the title. What it is ends up being something kind of between the two, a thriller set against a cultish religious backdrop with enough nuance to the premise that it should be an interesting movie. Unfortunately, that’s where you’d be wrong again, as errors in execution consistently undermine what might otherwise be a decent film.

So where does Holy Ghost People run afoul? We’ll get to some specifics where it consistently whiffed in a moment, but it boils down to the fact that in no aspect of this movie does it feel like the filmmakers nailed it. Yes, there are some good moments, some good choices. But it doesn’t feel like there’s an underlying understanding of why the choice worked in a particular instance. For example, there’s an extensive voiceover track for portions of the film, including the title credits, by the main character, Charlotte (Emma Greenwell). I’m not usually one for voiceover, but a lot of it actually works very well. This isn’t a film, so far as I know, based on any prior work, but there’s a very literary feel to the proceedings that suits the back country, pastoral ethic of the setting. This is the rare instance in movies where I wanted more voiceover. I liked hearing Charlotte’s take on things, how she rationalized her actions to herself. There’s an introspective and deeply subjective quality to the voiceover that adds a lot to the character, but more often than not, the voiceover is just used for dumping exposition.

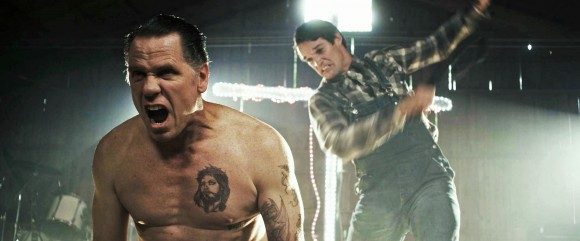

This sort of mixed bag crops up into nearly every technical aspect of the filmmaking. There were some nice shots, but they’d have been better served smooth instead of freehanded and shaky. There’s an intriguing commitment to mostly natural light, but some scenes are so obviously color corrected to the that you can still see the sun shining on one actor but not the person he’s talking to in the reverse shot. Perhaps worst is the editing, which, coupled with the questionable camera work, just feels too loose. There’s a lack of purpose behind each cut, and a tendency to linger to long on a number of shots. This hits the acting performances as well, although a few of the issues can be attributed to questionable casting. All of the actors are plenty competent, but none added significantly to my engagement in the movie. On this note, at least, it’s very interesting to compare this movie to Out of the Furnace, a movie with some headlining names that, in its basic premise, matches up with Holy Ghost People almost exactly: one sibling must venture into territory controlled by foreign, familial groups where the law doesn’t go in order to save his/her brother or sister. It may not be entirely fair to compare Greenwell, Joe Egender, and Brendan McCarthy to Christian Bale, Woody Harrelson, and Sam Shepard, and the cast is far from the movie’s biggest issues, but it’s inescapable that Holy Ghost People failed to draw me in and make me care about its characters nearly as much as Out of the Furnace, and some of that has to be laid at the feet of the cast.

But all that would be excusable if the plot was well-constructed. This may at first seem an odd critique, as I’ve already said I liked the premise, but bear with me. First, a brief primer on what we’re actually talking about. Charlotte enlists the help of Wayne (McCarthy), a local drunk but also a former Marine, to search for her sister, Liz, who has disappeared while living among a cult of snake handlers. Liz is a perennially recovering drug addict whom Charlotte denied assistance the most recent time she vowed to get clean, so Charlotte is dealing with some guilt about not helping her sister. And like I said, all that holds together pretty well. The problem comes in that it feels like the story routinely makes big leaps, both in its narrative and in its characters. We don’t know, for example, how Charlotte knows where Liz ended up, and that’s never relevant, though given their relationship as the movie lays it out, it probably should be. Wayne, meanwhile, owes nothing to Charlotte, and in fact barely knows her, but very quickly agrees to drive her (presumably) several hours away and pretend to be her father while living among the snake handling cult, known as the Church of One Accord. There’s a brief bit about Charlotte paying Wayne, but this is never made to be significant.

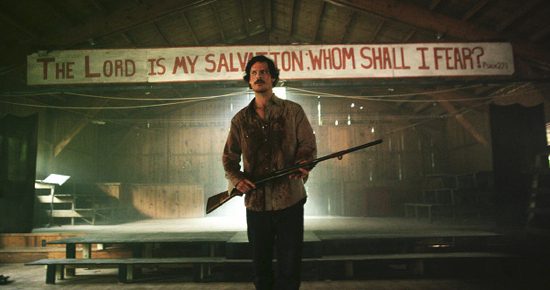

Likewise, the Church of One Accord is badly missing a sense of setting. The community never seems to be self-sufficient, but there’s never any mention of how they interact with the outside world; rather, they’re given to be wholly insular. There’s also a distinct lack of this group’s history. Their leader, Brother Billy (Egender, who also co-wrote and co-produced the film), is a young man, but there’s no sense of who came before him, or the route by which he started leading these other people in the cult. They’re all just…present.

Now again, all this may seem relatively minor, and for the first half of the film, I suppose it is. But where there is no firm foundation, there’s not much that can be built, and when the pic starts trying to pay off on a plot full of minor issues, those same holes quickly become gaping. The plot is driven forward, for example, by Charlotte’s decision (for reasons which are never clear) that to ask about Liz straightforwardly would be dangerous, and she and Wayne must assimilate into the cult by pretending to be interested in joining. This is where most of the early action takes place, as they’re led around and shown all the nice people (and the growing list of stuff that’s truly weird, not just unfamiliar). As the picture progresses towards the climax, both Charlotte and Wayne are asked to make decisions which lead them deeper and deeper into the cult, but there’s no sense of how these actions are contributing to the end of finding Liz. It’s almost impossible to talk about this without getting into details so MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD!

Towards the end of the film, Charlotte learns that Billy had a personal relationship with Liz, and Billy offers to show Charlotte where Liz is. Somehow, though, this consists first of Charlotte undergoing flagellation, then marrying Billy. Charlotte never once objects to this, never once asks what’s going on, just forges ahead. Likewise, the congregation of followers around Billy, despite the fact that most of them we’ve never understood as anything but good-hearted and convinced of their beliefs, makes no opposition to their minister marrying a woman he barely knows – even though (as is made apparent) Charlotte will be at least the third woman to become his wife in recent memory, after the first two were, erm, disposed of.

And we’re back in with the non-spoiler review.

There are a number of these overt leaps in logic, but there’s also just a lot of occasions where it feels we’re missing some backstory, maybe a couple of significant events. The movie does dig – inefficiently and without much art – into Charlotte’s past a bit, but what it does reveal never seems that significant compared to what I wanted to know while watching the movie.

The Verdict: 2 out of 5

To wrap this up before I really get rambling, you can see where someone thought the idea of Holy Ghost People was meritorious. What let that vision down was a consistent inability to execute at a high level. The movie is lacking quality in one or more aspects of its making in nearly every scene, and this makes the telling of its story feel very amateur. I give it credit for trying some things that are potentially interesting, but it feels like the biggest issue holding the movie back (aside from some truly mind-boggling holes in the plot) is a failure by the filmmakers to understand the details of what made their good elements work well and their poorer efforts fall short.