Growing up in Costa Rica was hard for a burgeoning film buff. Local movie theaters were a mess, only showing a tiny fraction of films that were released in the United States and usually delayed for several months while international distributors saddled them with abysmally-written subtitles or sloppy dubbing jobs. Oftentimes the only way to see anything but the highest grossing of blockbusters was through the healthy black market of low quality bootlegs. I spent most of my adolescent years watching Woody Allen and Robert Altman films recorded by pirates so incompetent that the heads of movie-goers sitting in the rows in front of them were an omnipresent fixture (which, in its own twisted way, kind of simulated the experience of watching the films in a crowded theater). Older films were no easier to find – usually it came down to praying that the local rental place still had that old VHS of Raging Bull lying around in the back, and that they hadn’t taped a football game over the second half. Getting to see films with any sort of regularity felt like a minor miracle, forget finding someone with whom to talk about them afterwards. Being a cinephile in my sleepy Central American home country was as much an experience of starvation and endurance as it was one of appreciation and consumption.

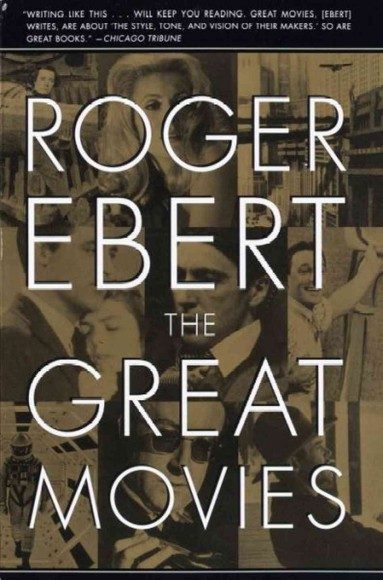

And then, when I was thirteen, my mother gave me a book as a Christmas present and everything changed. It was called The Great Movies, written by a fellow I’d never heard of called Roger Ebert. It was a collection of reviews and essays written on one hundred of the greatest films of all time. “All right,” I thought to myself, flipping through the book until I arrived at his piece on The Shawshank Redemption, one of about a dozen or so of the great films I’d seen, “let’s see if this guy is any good.”

Cut to four hours later, when I finally tore myself away from the book. I’d read the essays on every one of the films I had seen, proceeded to read all the ones on films I hadn’t seen but had heard of, and was now halfway through a review of something called Ikiru that was completely unknown to me. I wasn’t just absorbed; I was absolutely shocked at the way in which this man’s writing opened up film for me. I was already in love with film the way that a tourist falls in love with Paris after seeing the Eiffel Tower out of his hotel room window, but going through Ebert’s words was like being zipped straight to the heart of Montmartre while being given the world’s best crash course in French. Who was this man and how was he doing this?

It didn’t take long for me to figure out exactly who Roger Ebert was and to begin to follow the man with a kind of fanatical cinematic fervor. I sought out his thoughts on practically every movie that I saw. The Great Movies became gospel for me – I made it my mission to see as many of those films as I could, raiding video stores and stocking up on DVDs every time I went outside of the country. Ebert guided me to and through some of the weirdest and most challenging rabbit holes cinema has to offer. He was the reason I saw Antonioni’s L’Avventura, and his words helped me find meaning in every challenging, despairing twist. He led me to Kieslowski’s The Decalogue and showed me new possibilities for what film could be. He pushed me into watching Wenders’s Wings of Desire and… and we’ll come back to that one.

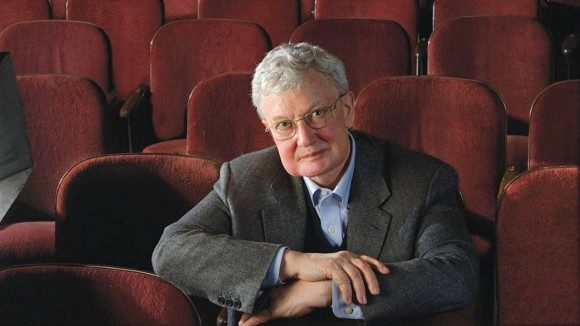

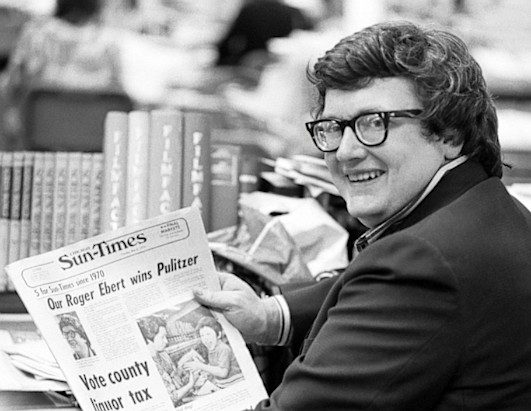

I’m not here to talk about who Roger Ebert was, or what his many, many accomplishments were. There are already a plethora of such articles on the Internet (and if you’re looking for one those, I recommend that you start here), and chances are that you already know what most of them say. Whether you agree with his opinions or his approach to film analysis, it’s hard to argue with Ebert’s title as the most famous mainstream film critic of his time. He was known to even the most uncultured of the film illiterate, and at the height of the man’s considerable powers his name was practically synonymous with the idea of film criticism. But with Life Itself, the documentary on Ebert’s life and his protracted battle with cancer, going into limited release this coming Wednesday, many of us who had our young cinematic minds turned upside down by Ebert’s writing are trying to answer some more difficult questions. What was it about his approach to film criticism that made him such a household name? Why did his words and his thoughts on film hold such power? Why, in short, was Roger Ebert the greatest film critic ever?

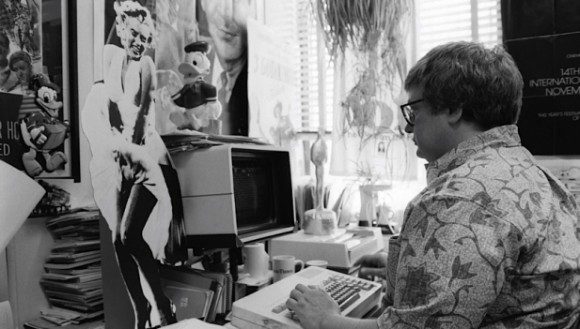

In seeking the answers to these questions, I have spent a lot of time over the past few days pouring over my old Ebert books, his website, and his reviews of films we both loved, films we both hated, and films we disagreed about. After spending a few days immersed in his writing, the first thing that asserts itself in my mind is what a master explainer Ebert was. There is an effortless didacticism to everything he writes, a straightforward way in which his writing can break down even the most complicated of ideas into its simplest form.

Part of this comes down to how literate a writer he was, how many points of reference he had to the world outside of film at his fingertips. There is a moment in his review of the classic documentary Hoop Dreams (made by, among other people, Steve James, the director of Life Itself) where he compares the behavior of a school administration to Dickensian villain Ebenezer Scrooge. Not the most obscure reference ever, but one that takes a degree of perspicacity to bring into a conversation about a documentary of low-income African American urban life. And yet it fits the film like a glove, explaining in a few words a complicated situation while also giving an impression of the film’s tone. In another review, this one of Milos Forman’s Amadeus, he namechecks Nabokov, P.G. Wodehouse, Tom Wolfe, Shakespeare, Michael Jordan, Picasso, John F. Kennedy, and Richard Nixon in a single paragraph devoted to explaining the relationship between the film’s two leads. His one hundred word paragraph leaves you with almost as clear an understanding of the dynamic between the two protagonists as sitting through two and a half hours of period psychodrama does. He always wrote about film as film, but he was never afraid to bring anything from comic books to politics into the conversation when he needed to illustrate a point.

Even more important than this, however, was Ebert’s unerring sense of what aspects of a film to bring up while explaining or unpacking it. It’s rare to find vague considerations of art or meandering platitudes in his writing. Instead, he wrote with exacting specificity, sketching out his ideas with concrete examples of moments in the film and rounding them out with rich accounts of his reactions to them. He worked from the film up, building arguments not on overarching structures but on details that are so eloquent they illustrate the ideas of the entire film. Consider this excerpt, again from his Hoop Dreams review:

We see how (…) some people never give up. Arthur [one of the protagonists of the film]’s mother asks the filmmakers, “Do you ever ask yourself how I get by on $268 a month and keep this house and feed these children? Do you ever ask yourself that question?” Yes, frankly, we do. But another question is how she finds such determination and hope that by the end of the film, miraculously, she has completed her education as a nursing assistant.

It’s just a tiny moment of resilience in the face of despair in a film that is full of them. The entire movie is built on this collision between the dreams of strong-willed individuals and situations so harshly bleak that they might just be able to break them, no matter how obstinate. Ebert could have gone on to explain that, the way that I just have, but… he didn’t need to. His writing already carried those ideas in it, and was all the more powerful not only for its brevity, but also for relaying the concepts through a concrete moment from the film.

This specificity is also the reason why Evert’s negative reviews are such a joy to read. Anyone can tell you that a film is bad, but Ebert’s takedowns of terrible films are so memorable because he took the time to look for the exact wording that made a unique and precise impression of how and why a particular film had failed. Consider this snippet from his Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen review: “If you want to save yourself the ticket price, go into the kitchen, cue up a male choir singing the music of hell, and get a kid to start banging pots and pans together. Then close your eyes and use your imagination.” Or this gem: “Battlefield Earth is like taking a bus trip with someone who has needed a bath for a long time. It’s not merely bad; it’s unpleasant in a hostile way.” Ebert was a master of snark (which I’ve only begun to sample here) because of the way in which he was able to conjure up an idea from concrete and particular examples. Like all great critics he didn’t just evaluate a film as good or bad; he crafted writing that impressed upon you a sense of what watching the film would be like.

But at his best Ebert went beyond simple summation or explanation. The critic that can evaluate a film, break it down, explain it, and help us to understand our reaction to it is rare enough to merit recognition and praise, but by no means unheard of. But something about Ebert’s pieces made this process so simple and accessible that it sets his work apart. His writing is possessed of such stunning clarity and simplicity that even the most complicated aspects of film seem to lay themselves out organically when he takes to them. Consider this explanation of a scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Notorious:

Alicia awakens with a hangover, and there is a gigantic foreground closeup of a glass of Alka-Seltzer (it will be paired much later in the movie with a huge foreground coffee cup that we know contains arsenic). From her point of view, she sees Devlin in the doorway, backlit and upside down. As she sits up, he rotates 180 degrees. He suggests a spy deal. She refuses, talking of her plans to take a cruise. He plays a secret recording that proves she is, after all, patriotic–despite her loose image. As the recording begins, she is in shadow. As it continues, she is in bars of light. As it ends, she is in full light. Hitchcock has choreographed the visuals so that they precisely reflect what is happening.

Which brings me to Wings of Desire. Wim Wenders’s 1987 film about the trials and tribulations of invisible angels in modern day Berlin has a reputation for being difficult. Large sections of it consist of characters silently watching humans leading their lives having no ability, and at times no desire, to intervene. There is a plot, of sorts, but it doesn’t begin until you’re well into the movie and develops at a slow and unusual pace. The first time I tried to watch the film I fell asleep twenty minutes into it. The second time, I feel asleep fifteen minutes into it. But the third time the film grabbed me in a way few films ever have. I hardly stirred for two hours as the slow, terse film filled me with emotions I honestly could not have explained as I was watching it. By the end of it I was crying and had no clear idea about why. As the credits began to roll, I practically ran to pick up my copy of The Great Movies. “Thank God I have Roger to make sense of this!” I thought to myself.

Instead, what I got was a film review that seemed to have been written by a man that was as uncertain about the film’s majestic power as I was, equally unsure about why it held its odd sway over us. The piece ended with this paragraph:

Wings of Desire is one of those films movie critics are accused of liking because it’s esoteric and difficult. “Nothing happens but it takes two hours and there’s a lot of complex symbolism,” complains a Web-based critic named Peter van der Linden. In the fullness of time, perhaps he will return to it and see that astonishing things happen and that symbolism can only work by being apparent. For me, the film is like music or a landscape: It clears a space in my mind, and in that space I can consider questions. Some of them are asked in the film: “Why am I me and why not you? Why am I here and why not there? When did time begin and where does space end?

“For me…” In the end, these two simple words might be what made Roger Ebert the greatest critic of all time and a man capable of touching so many young hearts and minds. He could explain a film’s inner workings, but that was never his end goal, it was always in service of something else. He was always focused on doing everything he could to explain his reactions to films, and he always did this while being conscious of how that might aid us with our reactions. He was not in the business of answering questions or imposing definitive statements upon his readers, but rather in the one of guiding, of humbly offering a cinematic companion to help us understand our own journey better. He gave us a point of reference, a way of asking, “Why was my reaction this and not that? Why do I love this and hate that?” Ebert’s writing never just told us what to think about a movie, it always set aside a space for our own opinions to grow as we read his perspective. He was the greatest film critic not because he offered us final destinations for our cinematic thinking, but because he opened up his mind and his heart to equip us with what we needed to progress on our own journey.