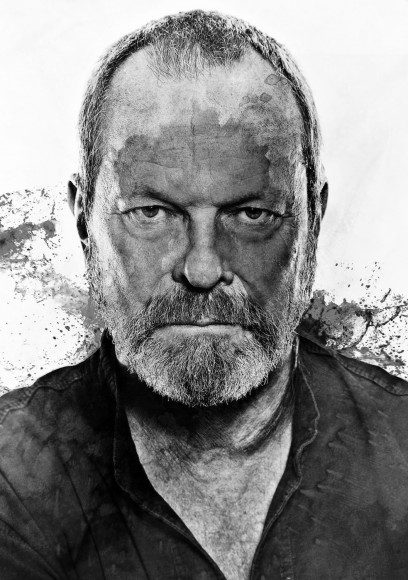

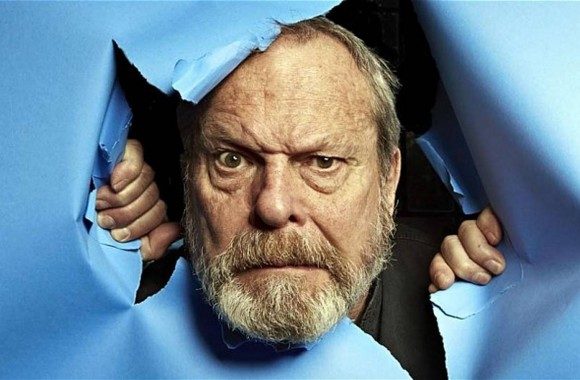

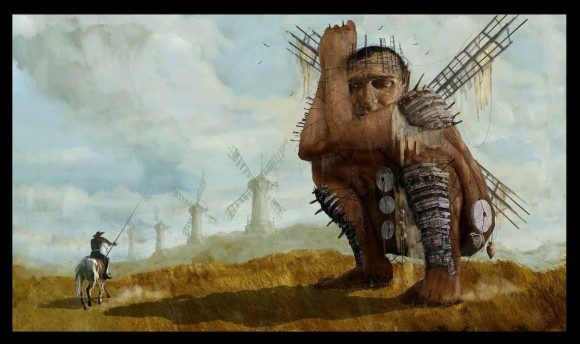

Here we go again. It seems that Terry Gilliam, our friendly neighborhood maverick gonzo director, is going once more into the breach, dear friends. Now that he’s wrapped up work on the upcoming Zero Theorem, reports have began to surface that Gilliam is going to once more attempt to make The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Press coverage from earlier this month has the director saying that principal photography will start immediately after Christmas of this year. While the exact details of the story and the involved parties remain incredibly sketchy beyond some general descriptions and glimpses at concept art, it looks like this is happening. Batten down the hatches, everyone, this is not a drill.

Oh, I’m sorry, do some of you not know what The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is? Oh dear. Well, take a seat. And buckle up.

The short version: director Terry Gilliam, perhaps still best known as the one-man animation wing of comedy troupe Monty Python, has famously been trying to make an adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes’s classic novel Don Quixote for the past, I am not kidding here, twenty-five years. By his own estimate, Gilliam has restarted development on his Quixote adaptation a whopping seven times, working on various iterations of the script and assembling the necessary assets since the early ’90s.

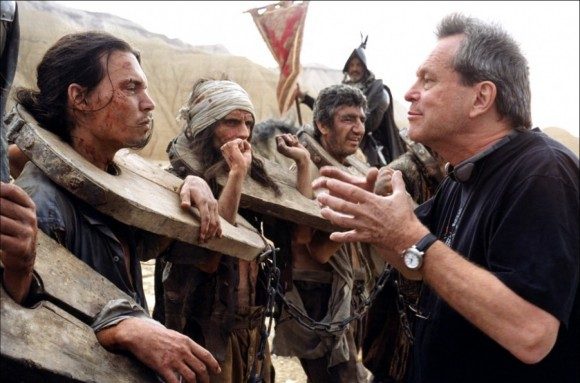

The most famous of these attempts came at the turn of the millennium, when a version of the film titled The Man Who Killed Don Quixote went into production starring Johnny Depp and French actor Jean Rochefort. The production, budgeted at about $32 million, was beset by set-destroying flash floods, audio interference from an adjacent air force base, and health problems that forced Rochefort to abandon the production almost immediately. A month after shooting began, the film was officially canceled, and all the film’s assets, including its script, passed to the insurance company that oversaw production. Gilliam then spent the following years recovering the rights to his project, finally starting a new production in 2008, this time with Robert Duvall and Ewan McGregor in the leads. Things looked promising for a while, until an announcement revealing that the film’s financing had collapsed just as the film was ramping up to enter into production. (That’s just the cliff notes. For the much longer, much more complicated, much more painful version, click here.)

And now the 73-year-old Gilliam is about to get back on that horse.

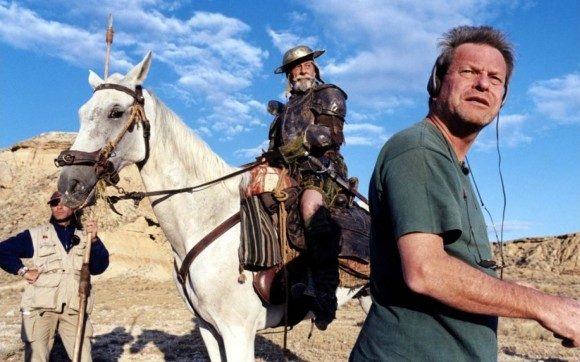

Gilliam and Jean Rochefort on the set of ‘The Man Who Killed Don Quixote’. Just off screen: something going disastrously wrong.

Terry Gilliam’s career has never exactly been a smooth road. His track record is one of the most beset and arduous for a major director in the past fifty years. His dystopian epic Brazil was famously re-edited by the studio and given a new, completely mismatched ending. 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Muchausen underwent last minute renegotiations with the studio, suddenly found itself $10 million over budget on day one of shooting, and was forced to undergo massive retooling on the fly. The set of The Brothers Grimm was riddled by a very public dispute between Gilliam and the film’s producers, which led to various key crewmembers being fired and replaced without the director’s consent. 2009’s The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus had to be shot around one of its main stars’ (Heath Ledger) mid-production death and the director being hit by a bus and breaking his back. Gilliam has famously said that he considers resistance during productions one of the main animating factors of his career, saying, “Everything is equal to me until somebody says ‘no.’ ‘What do you mean, “No”? Why?’ And now we’ve got something to concentrate this energy on and you solve the problem one way or the other.” But just the fact that this man was able to get all of those films made but has been unable to get Don Quixote to screens is enough to give pause.

This is a film that is still teetering on the brink between completion and the abyss. It’s been in the making for so long and seen so many false starts and abortive productions, yet its makers are still diligently (some might say foolhardily) trying to bring it into the world. We’ve spent so much time hearing about the film, looking at concept art, even going through Lost in La Mancha, the excellent and utterly heartbreaking documentary that covers Gilliam’s 2000 attempt to shoot the film, that by now getting to see it would feel a little bit like finally getting to discover who the murderer was in Charles Dickens’s incomplete The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

There’s something fascinating about these unfinished passion projects that artists leave us glimpses of. They have a way of feeling like the works that would have been most representative of the men behind them. Not the best, mind you, nor the most cohesive or the most successful – just the ones that seem most geared towards their collective preoccupations. Nothing in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s completed canon feels as visually excessive or politically subversive as the tiny gleams we have of his version of Dune. Nothing in Kubrick’s oeuvre marries grandiose scale, historiography, and internal psychodrama the way his years of research for Napoleon seem to show. The Day the Clown Cried sounds more eloquent about the relationship between tragedy and comedy than anything Jerry Lewis actually finished, and The Other Side of the Wind sounds like the definitive film on the alienation of art makers by a director who had to fight tooth and nail to get practically every one of his films made (we’ll get back to him). We can’t know any of this for sure, of course, but that’s the impression that these titanic undertakings give off at a distance.

The same goes for Terry Gilliam and Don Quixote – it’s actually difficult to imagine a property better suited for the director’s particular sensibilities. Gilliam already considers man’s inability to distinguish between reality and fantasy the main thematic cement of the majority of his films, and Cervantes’s tale about an aging man who starts to believe he’s actually an old school medieval knight, not to mention the various men and women who play along for their own purposes, offers multiple layers to play with this concern. Gilliam’s visual aesthetics often boast a piecemeal, haphazardly assembled look, and nobody has done this better than the classic character that literally put a suit of armor together from pots and pans. Fantasy and surreal visuals? Check. You even see echoes of the heroically deluded hero in characters from multiple preexisting Gilliam films, from Parry in The Fisher King to the titular swashbuckler in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. There’s a degree to which all of the director’s previous work feels like preparation for this quixotic passion project. Bring on the windmill giants.

Speaking to his own ongoing obsession and inability to just abandon this project, Gilliam said:

Probably [can’t let The Man Who Killed Don Quixote go] because I can’t make it. That’s why. If I could make it I could let it go [laughs]. Certain things just possess you, and this has been like a demonic possession I have suffered through all these years. The very nature of Quixote is, he’s going against reality, trying to say things aren’t what they are but how he interprets them. It’s ridiculous and it is who I’ve become, with age. In a sense, there is an autobiographical aspect to the whole piece.

Perhaps that is the most fascinating aspect of this entire project, the thing that makes it feel the most representative of Gilliam’s oeuvre as a whole. For such a long time the director has been railing against the version of reality that the world around him has tried to impose on him, and has worked with, around, and against that tension. He has constantly tackled windmills while insisting that they are giants, and on some occasions he’s actually managed to transform them into his vision. But never has reality seemed as dead set against budging as it has for this project.

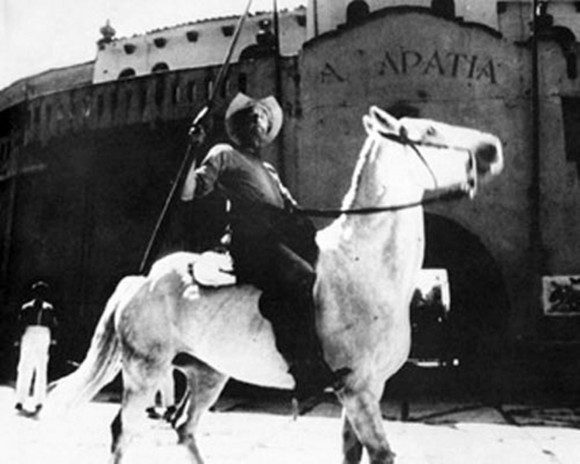

Which brings me back to Orson Welles. By the time that Welles died in 1985, he had a string of half finished and abandoned film projects around him, but two rise as the most infamous of the bunch. The first is the aforementioned The Other Side of the Wind, a drama about an aging director trying to get one last film made before his death during the collapse of the Hollywood studio systems. The other one was a modern retelling and updating of… yup, you guessed it: Don Quixote. Started in 1955, the film would undergo a series of shoots, reshoots, recasting, retoolings, and rewritings while enduring a series of financial and legal problems on the side. Welles spent practically the rest of his life editing the material he shot and planning further shoots, speaking about his intentions to complete the film all the way up to his death. Welles’s version of Don Quixote was in an uneasy state of production from 1955 to 1985, even longer than Gilliam’s madcap epic (so far).

Now, I don’t want to imply that some sort of curse exists around the Don Quixote property, or suggest that the material is unfilmable or anything like that. Film versions of the story have existed since the 1920’s, and Don Quixote has been adapted into everything from a musical to an East Asian action adventure. Don Quixote can definitely be filmed. What I am saying is that it’s fascinating that these two directors, men who faced so much opposition and difficulty in filmmaking throughout their lives, would not only come to be obsessed with the same property but also face so many of the same travails, setbacks, and difficulties in bringing it to life.

Don Quixote, the character in Cervantes’s novel, comes to a sad end. After losing a duel to another man from his village, he is forced to give up adventuring for a year. During that time, his fantasies and unique ways of seeing the world fade away, he grows ill, and he dies a lonely, sad old man. Orson Welles’s adventures in the world of Cervantes didn’t come to a much happier conclusion. His film was never finished, and it remained one of his most consuming obsessions during his final years. Now it’s Gilliam’s turn to take a swing, and reality has so far proven as obstinate and immovable as it did for Orson Welles. And yet, after two and a half decades of punishment, the director is still charging forward, steadfast in his belief that things will be different. Who knows? Maybe this time the windmills will really turn into giants.