The catastrophe of Sin City: A Dame To Kill marks the second consecutive cinematic failure of comics icon Frank Miller. His previous work as writer-director, the even worse failure The Spirit (2008), seemingly exiled him from Tinsel Town until Robert Rodriguez decided to return to the green screen well once again. The Spirit, a mistake on every level, is even more disappointing since it was the introduction for many to Will Eisner’s groundbreaking, ahead-of-its-time comic book creation.

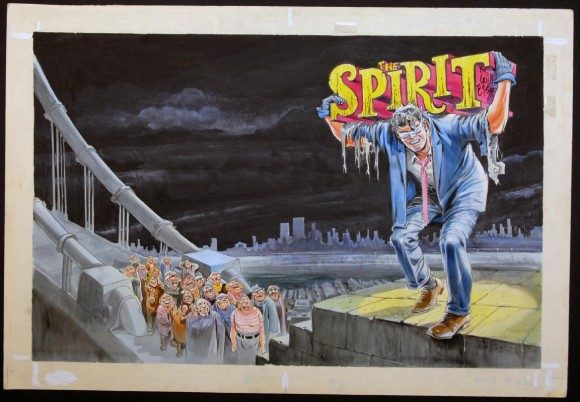

First appearing on June 2, 1940, The Spirit never received the name recognition amongst the general public of his Golden Age contemporaries Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman, but his legacy could possibly rank among that of the holy trio. Medium notables such as legendary misanthrope Alan Moore (Watchmen) and Neil Gaiman (Sandman) have described how the work and its creator were among their greatest professional inspirations. The main annual honor for comics is The Eisner Award, named after the creator of The Spirit, Will Eisner. And The Spirit has appeared in some graphic form every decade since its original run ended in 1952, with the medium’s biggest names taking their own crack at the man with the blue trench coat, domino mask, and fedora.

To truly understand why The Spirit is important, The Best of the Spirit is a good starting place. Having some basic knowledge of Golden Age comics is crucial as well, because it’s hard to understand why it’s so different from its counterparts without having that baseline of comparison. The short version is that a lot of those early superhero stories were relatively simple and straightforward – Batman or Superman or Green Lantern or Flash would encounter and then defeat the villain of the week, be it some monster or some mob guys. Their worlds and cities existed, but only as a setting.

But Eisner went against the grain. He might have been the first to truly appreciate the universe, in this case Central City, as much as the hero – the perpetually disheveled “everyman” detective Denny Colt who “died” and returned as The Spirit to fight crime. Certain issues barely featured The Spirit at all, placing him in the background or only catching up with him at the end of the case. Some stories would focus primarily on a low level gangster, and in one instance, an entire story was framed first person through the eyes of the perpetrator. The innocent citizens of Central City also got their chance to shine, with “The Story of Gerhard Shnobble” a particular high point and one of the most emotionally affecting comic books of any age.

Will Eisner was among the first to realize that comic books could be more, could be a medium worth respecting, and his mission continues even after his death. During the early years of the medium, he was forward thinking in his ability to defy convention by telling stories through a variety of that era’s most popular styles and doing so through respect rather than parody. From film noir to horror, from fantasy to sci-fi, his Spirit books folded them all into its world – complete with a wry, dark sense of humor and occasional garnishes of tragic romance. It took decades for The Spirit‘s use of genre mashing to come into vogue. One can easily see how Eisner at least partially inspired the main characters of Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.

So with The Spirit carrying such remarkable history and the respect of those who see comic books as more than easily digestible pabulum for children, how did Eisner-protégé and comics legend Frank Miller botch the movie so horribly? By missing the point entirely. Put simply, The Spirit lacked The Spirit’s spirit.

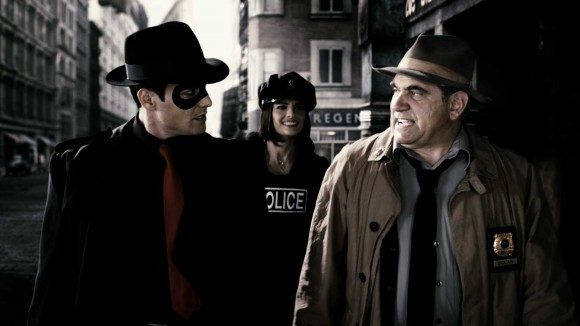

The Spirit is Frank Miller’s sole directorial effort (some segments of both Sin City films aside) … and he ended up doing a cheap visual retread of Sin City. Gone were the humanity, heart, and humor of Eisner’s creation – not to mention the beautiful artwork – replaced by dark and unpleasing CGI sets and performers who were unable to fully commit to this hyper stylized universe. But it’s not necessarily their fault. Frank Miller himself didn’t seem to understand precisely what he was going for – ultra dark noir, post-neo noir, noir parody, Sin City lite, Sin City dark?

As the titular character, Gabriel Macht (Suits) was unable to walk the difficult tightrope of charming self-awareness and buying wholeheartedly into the ridiculousness surrounding him; neither winking to the audience nor pretending that they don’t want the acknowledgment. It’s the type of role we’ve seen someone like Nathan Fillion (Firefly), or James Franco (performance artist “James Franco”) to a lesser extent, execute with aplomb. Macht could alternate between serious and cartoony, but it’s the understandably difficult merging of the two elements that this property (which falls under the DC Comics brand) requires.

The movie also missed the appeal of the character and his tales. While The Spirit rose from the dead in both the comics and the film, the comics version regularly appeared disheveled and could be injured. Miller made him almost completely invulnerable and immortal, which cost The Spirit his hard luck quality. Even his dedication to the city is treated secondary to his personal issues related to a string of sexual almost-conquests so long it would make Rescue Me‘s Tommy Gavin blush. While the good girl, the femme fatale, the fast talker, and other female archetypes existed in The Spirit (comics), as they would in every great noir tale, they never seemed as crucial to the character as they did in this movie.

The other actors (including Stana Katic, Sarah Paulson, Eva Mendes, and Jaime King) didn’t fare much better, as they all seemed to think they were in entirely different films from one another. Though it is somewhat amusing to see Samuel L. Jackson (as main villain Octopus) and Scarlett Johansson (as his number two Silken Frost) working together as bad guys four years before they decided to switch sides to lead the organization behind a slightly more successful superhero franchise.

Although The Spirit (comics) could leap successfully from genre to genre, The Spirit (film) could only manage major tonal inconsistencies. Within a couple of minutes, the main character has a seeming death wish and then engages in slapstick fight scene with cartoon sound effects. The classic broodiness of the noir detective pining for the femme fatale loses something when it’s surrounded by overly fake sets, CGI-enhanced everything, and a bizarre penchant for Nazi fetishism (which, according to my readings, was not part of the Eisner mystique).

With all the reboots afoot (Batman, Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, etc.), it’s The Spirit that most deserves a second chance at live action glory. However, it’s not a property that is best suited towards film. The comic’s penchant for not always having The Spirit front and center perfectly fits the innovative approach towards long-form storytelling that television and the Internet welcome. Most movies, particularly in the superhero genre, need a main character, while serialized programming could easily subscribe to the Eisner tradition of following The Spirit for several episodes before putting him in the background for the next one. Instead of hoping that running from genre to genre could work in a 2-hour long feature, a series could more easily allow the individual story to dictate that particular installment’s style, much like it did in the comics.

Some of the best examples of a television series paying homage to multiple genres without it appearing gimmicky or forced have come from unabashed comic book aficionados. Doc Hammer and Jackson Publick of The Venture Brothers and Ben Edlund of The Tick are great examples of showrunners who have genuine appreciation of, rather than derisiveness towards, genres past and present and the knowledge to work them into a superhero framework. That is how The Spirit differentiated itself 70 years ago, and that is why in our meta-focused, post-modern, superhero movie-laden world, The Spirit might be the hero we both deserve and need.