As a kid, I relished in every opportunity to sing and dance to my favorite songs. My friends and I would either copy choreography from our favorite music videos (I’m looking at you, Britney Spears) or make up our own. The transition from that to theatre kid was a natural progression. Having suffered from trauma, the idea that you speak until there is nothing to say and sing until the only other way of expression is dance spoke to me on a deep level. The world of musical theatre was my escape. I would spend hours re-watching my favorite movie musicals, committing every scene to memory. I believe that theatre can save your life, even if it’s for a few hours.

Musicals carry universal themes and truths and present them through captivating storytelling. Some musicals are predictable, while others surprise you with the depth they can achieve with a comical overtone. It is more exciting when you realize how a single line in a song from act one has foreshadowed a pivotal plot point later. Sometimes I will talk to someone about a musical, and they will bring out something that I didn’t see until they said something. The most recent was a friend telling me his unpopular opinion for Dear Evan Hansen. He believed the show should never have been made because of how Evan gaslights the Murphy family. In the film Little Shop of Horrors, the theme prominently displayed is codependency among the characters.

The characters with codependent relationships are Seymour (Rick Moranis) and Mr.Mushnik (Vincent Gardenia), Seymour and Audrey II (Levi Stubbs), and Audrey and Orin Scrivello D.D.S (Steve Martin). At least four of the songs have lyrics that show the severity of each relationship’s codependency and why the particular character sticks around. The other songs are informational and give insight into a character on the partner that the character is giving their excessive emotional or psychological reliance on.

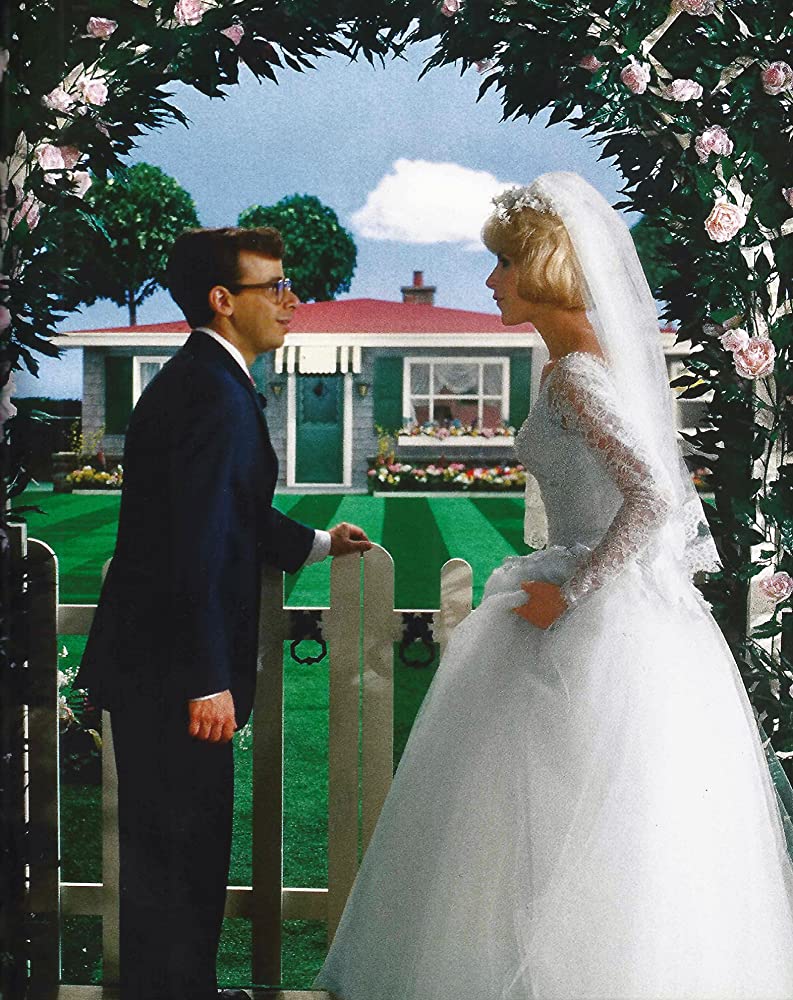

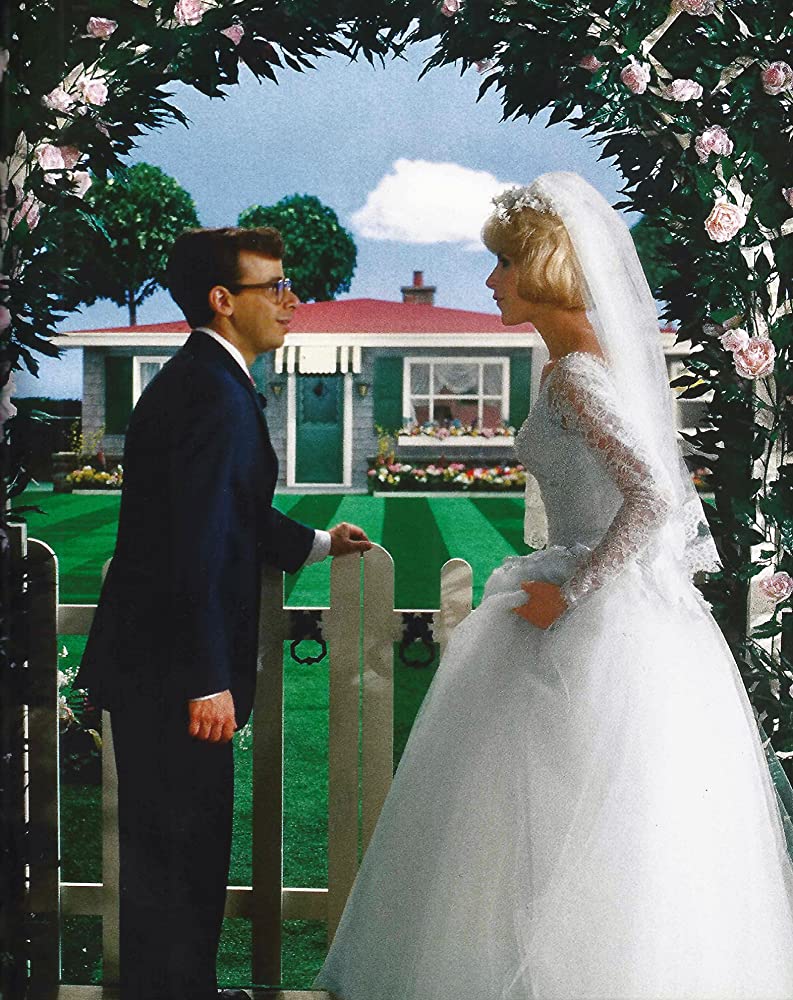

Since its debut in 1986, Little Shop of Horrors has reached cult status. A combination of campy B horror scenes with comedy has kept this film just under the radar and underappreciated. Little Shop of Horrors follows Seymour, a nerdy orphan and plant enthusiast who works at Mr.Mushnik’s flower shop. Seymour is infatuated with his out-of-his-league co-worker Audrey (Ellen Greene). His luck changes when he finds a strange and exciting plant after a random total eclipse of the sun.

After the “Prologue,” the first musical number is “Skid Row.” Within the lyrics of the song, Seymour describes his relationship with Mushnik. Seymour was an orphan, and Mushnik took him in, gave him a job and food. Besides kindness, Seymour recounts that Mushnik mistreats him and calls him names. He defends this and agrees by saying that he is. Mushnik rejects Seymour and Audrey’s idea to display Audrey II in the flower shop window until a customer comes in and buys flowers after seeing Audrey II. Instead of celebrating and taking Seymour out to dinner like he initially said, he instructs Seymour to stay and take care of Audrey II because he is “counting on” Seymour.

The codependency between Seymour and Audrey II is more intense than between Seymour and Mushnik. Before Seymour knows the full extent of what Audrey II can do for him, he relies on the plant to get himself out of skid row. Frustrated with not knowing what kind of plant Audrey II is, he sings the song “Grow For Me.” Once he gives Audrey II his blood, the plant grows, reinforcing that if he literally opens his veins, they will both get what they want. That their relationship can be mutually beneficial comes to a head during the “Feed Me” number. Audrey II begs to be fed more than mere drops of Seymour’s blood. Audrey II stresses that he needs to “grow up big and strong.” Seymour initially refuses but is convinced when he is promised Audrey II will “make it worth his while,” and if Seymour gives him what he wants, he can provide Seymour anything he desires. Audrey II emphasizes that Seymour had nothing until Audrey II came along. The “Feed Me” song also shows that their meeting wasn’t a coincidence; Audrey II chose Seymour.

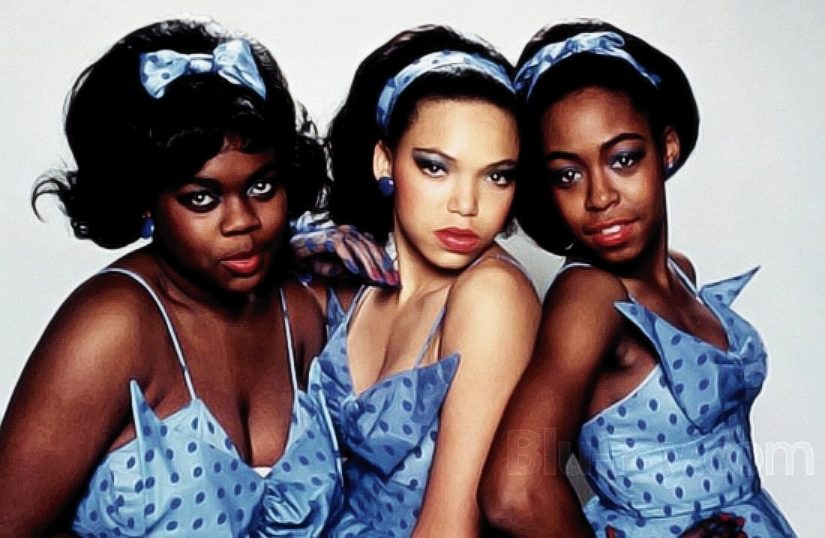

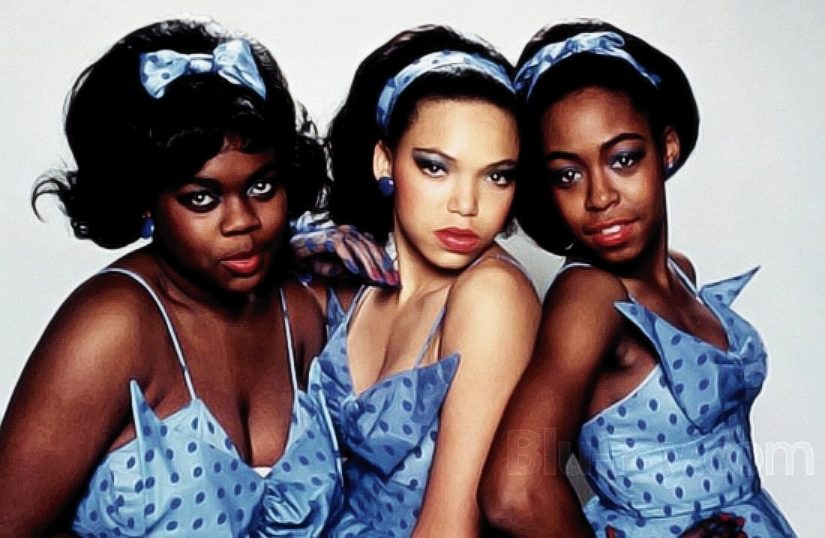

Finally, Audrey and Orin Scrivello D.D.S are in a codependent relationship and an abusive one. Right away in the “Skid Row” song, Audrey acknowledges that relationships are “no-go,” and the boys will “rip your slits.” Throughout the film, Mushnik warns Audrey not to date Orin, that he is no good. Audrey repeatedly will defend not only Orin but her decision to continue dating him. She claims that he is the “only fella” she has, he’s a “professional,” and she “deserves” the relationship. Audrey also says that she doesn’t deserve a nice guy like Seymour. Her rationalization is because of her past mistakes. There is a scene where Audrey’s arm is in a sling after Orin beat her up. She defends staying with him because leaving him will make him angry. She reasons that if he can break her arm when he loves her, she cannot imagine what he can if he is mad. The Greek chorus girls (Tichina Arnold, Michelle Weeks, Tisha Campbell) point out that she “suffers from low self-image.”

As an art form, the theatre has always been a place that has highlighted issues prevalent beyond its walls. If nothing else, Little Shop of Horrors is the culmination of losing yourself in a one-sided partnership. Codependency can take different shapes depending on situational variances. Seymour and Mushkin represent how codependency develops in a familial setting. Mushkin was like a father to Seymour. Even though he had a form of love to Seymour, it turned into Mushkin depending on Seymour’s giving, resulting in Mushkin taking advantage of Seymour and trying and pushing Seymour out to have all the Audrey II glory and fame to himself. Mushkin was the power figure and narcissist who needed to be made happy, while Seymour was the low self-esteem giver who needed to give everything from himself to feel like he was needed and loved by Mushkin, his father figure.

Typically when you hear about codependency, someone is referring to lovers. While Seymour and Mushkin are a great example of familial codependency, Audrey and Orin are a more traditional example of codependency. Seymour and Mushkin’s situation was subtle, while Audrey’s situation was on the extreme. Like Seymour, Audrey is the low self-esteem giver to Orin, the narcissist. Audrey sacrificed any resemblance of a personal life, turning down invitations to do things throughout the film so she can be available for dates with Orin. He used her low self-worth to his advantage and even referred to it as “training” Audrey. She felt loved and needed by continually catering to Orin’s every need a whim, even when it meant having to hide broken bones and black eyes.

Seymour and Audrey were both the typical low self-esteem codependent givers. As much as their “takers” were unhealthily toxic for them, Seymour and Audrey had bad habits that fed their codependency. Audrey was obsessed with giving all her time to Orin, where Seymour obsessively gave away his free time and all to care for the plant and even lived at the shop, which was more beneficial to Mushkin. Seymour was an unhealthy caretaker spending all his free time caring for the plant. Then he gave his blood to the plant to feed it for a while. Neither had outside lives. By the end of the movie, they broke the chains of these horrible relationships and developed better habits. Seymour and Audrey began to be together, but they had mutual respect and healthy dependant tendencies. Codependents have dysfunctional communication tendencies, but with each other, they talked as much as they listened to each other. In contrast, the plant, Mushkin, and Orion all never listened. Audrey and Seymour wanted to have a life where they mutually cared and did things for each other and received love back where the codependent relationships were mostly one-sided on the giving and receiving ends.

Codependency creates stress and leads to painful emotions. Shame and low self-esteem create anxiety and fear about being judged, rejected, or abandoned; making mistakes; being a failure; feeling trapped by being close or being alone. Seymour and Audrey went through all the painful emotions, but by the movie’s end, not only did they break their chains by having their codependents removed from their life, but they pushed aside these unhealthy feelings to open up intimately to each other as well as decide to be with each other essentially find a healthy dependent relationship characterized by mutual love respect and healthy tendencies to break the codependent ones. What’s the point of leaving one toxic relationship if your tendencies push into another similar codependent relationship? The film’s ending shows so many aspects of codependent relationships how psychologically codependents feed off their deeply ingrained bad habits and what a healthy dependent relationship looks and feels like and leaving us with an encouraging sentiment that can last a lifetime.