For all of its flaws, Tomorrowland broached a subject that very few movies really play towards – the power of imagination. It’s why a lot of us fell in love with movies in the first place, but at least for me, the “magic of cinema” seems to have lost some of its luster. This cynicism could be due to a combination of multiple factors – simple aging, having seen so many movies that the chance of being wowed is less and less likely. But while those contribute, I believe there’s a singular culprit that makes up most of the problem: the glut of CGI (not CGI itself, but its prevalence and use) over and above practical effects and other more tangible filmmaking techniques.

As I said in my previous article about Tomorrowland, the “A Boy and his Jetpack” sequence at the start stole the movie. Yet it captured the audience’s attention not because of the CGI wonderland known as Tomorrowland, but more the jetpack itself. A ramshackle, cobbled together effort with “Electrolux” proudly emblazoned on its side. It didn’t matter that it didn’t work. The object itself was a testament to ingenuity. Grabbing random items from the garage and slapping them together with the dream to create something wondrous just out of spare parts and an inventive spirit – Frank’s pride came less from the jetpack working and more from his successful creation of something new and fantastic (that is to say, out of fantasy).

The enjoyment of the scene came less from seeing Tomorrowland itself and more with seeing the combination of hope and impossibility imbued in the jetpack. Later moments in the movie have similar elements – Frank’s house with the rising staircase and trap doors, the Eiffel Tower sequence, for example – but they were disappointingly few and far between. Yet these parts stood out for me more than Tomorrowland itself because they all contributed to the childlike sense of wonder in invention that this movie wanted to have far more than any CGI robot or elevator platform could.

But why is that? Really it’s two questions. First, why is it important that movies harness the spirit of invention? And second, why is it that practical effects seem to be so much better at this?

Let’s start with the second question and work backwards. Gears, pulleys, and levers operating in a Rube Goldbergian way (like Doc Brown’s house at the start of the original Back to the Future) will always have something special that CGI lacks. To be fair, modern technology exists in a form that people could have never dreamed of years ago. The capabilities of tablets and phones are lightyears ahead of what was considered possible when reel-to-reel computers were in vogue.

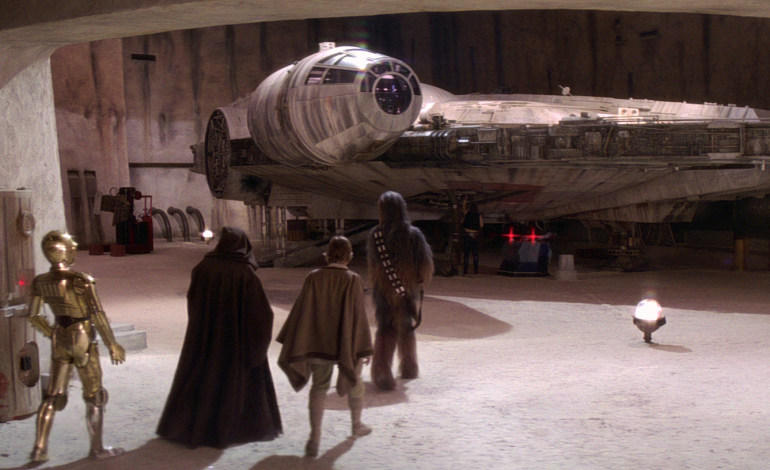

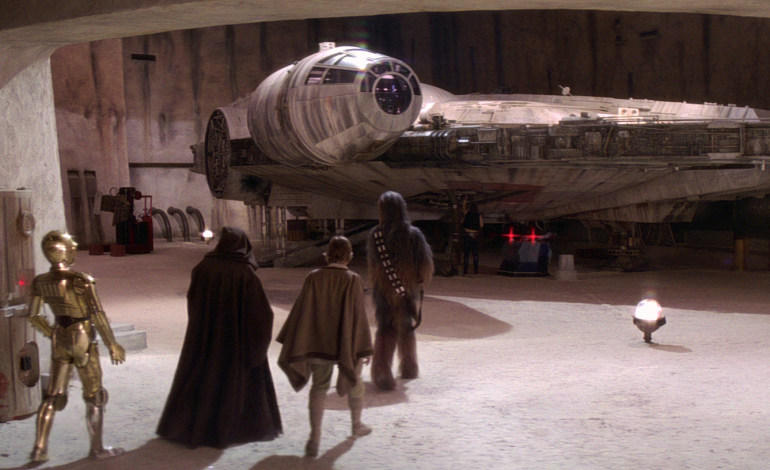

But it’s not so much that the practical creations look more “real” (even though they generally do, bearing the scratches and dirt that CGI strives to eliminate) but that they inspire viewers to believe that they could do these things themselves. From our youngest ages, we’re used to working with solid objects. Lego sets, building blocks, and models allow us to replicate things we’ve seen and even create new ones. A lot of practical effects are an extension of that, except on a much higher level. We watch sparks fly as Han and Chewie work on the Millennium Falcon, and we believe that not only is something so incredible actually real, but that we could create something like it with enough time and effort. There’s a tangibility that inspires us to try, even when we fail.

And that’s where fostering imagination and caring for inventiveness pay off in spades: audience engagement. When we believe something is possible, we internalize it as real and meaningful in our own life, even if it’s a spaceship. CGI can do this on occasion. Despite the rest of the movie failing on nearly every level, Chappie made us believe in the reality of its title character through some of the best, most detailed CGI in the industry blended with a grungy, lived-in setting selective use of practical effects. Unfortunately, for the vast majority of the time, CGI lacks this level of interconnectedness. We can “tell” when something’s weight is off by the way it moves, or the more cartoony effect when a CGI “person” tumbles across the street. Even if models can’t perfectly replicate the physics, any form of solid weight gives a better feeling of mass; we already want to believe in the magic of the movie, we’re looking for something to confirm our suspicions of reality.

But Chappie is only the latest example of how effects – computerized or not – can be used well. Go back further, and Jurassic Park was among the first movies to merge CGI and practical effects, and it inspired us by breathing life into creatures we already recognized as animals and had an existing tangible connection to. (What kid hasn’t seen pictures of dinosaur skeletons, or the skeletons themselves?) Go back further, and we have Star Wars making the boundless unknown of space reachable through recognizably mechanical vehicles. Go back even further, and you have The Wizard of Oz, which still ranks among the most visually impressive films of all time.

Is this affection mostly based in nostalgia? I don’t know. Maybe. Possibly. Maybe. But one cannot deny the still one-of-a-kind look of the land or not feel a genuine appreciation of the sheer craftsmanship applied in creating that world. When you look at Oz in the original The Wizard of Oz (and even 1985’s Return to Oz), you believe they’re in Oz. It doesn’t necessarily look “real,” but it shouldn’t look real. It should feel slightly off. The sets that comprise 1939 feel magical yet lived in yet somewhat disquieting. You look at 2013 Oz from Oz, The Great and Powerful

And you get a nice computer wallpaper.

Both movies are heavily effects driven; to pretend they aren’t is to be completely disingenuous. But there’s a quality here:

that isn’t in the other picture. Or maybe it’s nostalgia plus the iconic indoctrination playing tricks on me.

Those elements are important, but it’s his earlier film Super 8 that might be the better example of why he is suited to take command of a series with such a well-loved history of fostering inspiration. Before Super 8 devolved into a CGI alien destroying a small town (in a pretty respectable homage to early Spielberg), it was all about kids trying to make a movie using practical effects and make-up. Seeing Abrams’ tangible connection to these element of filmmaking showed that he understood a big part of why Star Wars was so important to so many people.

This look back at his own (presumed/imagined/desired) childhood had more to do with just why Star Wars has remained in our memories than seeing the USS Enterprise pretend to be the Falcon. Thankfully, the teasers for Star Wars: The Force Awakens, not to mention what we’ve seen from the now-wrapped set, reflect that he has carried this lesson over. At any rate, we can only hope so.