The concluding chapter of this epic Hobbit franchise, The Battle of the Five Armies, hits theaters this week, but one cannot deny that the kind of anticipation and excitement that made Return of the King into one of the highest grossing movies of all time is, well, sorely missing. Sure people will see it (myself included), but this has gone from feeling like an event to feeling like an obligation. At this point, the most interesting thing to come from the franchise is that “Hobbit-sized” now means unreasonably large.

The biggest issue facing The Hobbit from the start was that it would be naturally likened to the earlier, superior Lord of the Rings trilogy. While in many areas this would be a bit unfair – a film franchise should be allowed to stand on its own without having to ape or live up to its predecessors – The Hobbit and director Peter Jackson regularly made decisions that almost challenged us not to do so (not the least of which was expanding a single book into a full-fledged trilogy; the original two-movie plan was far more reasonable, as we would soon find out).

A major point of contention was the severe tonal shift between the book and the films. Unlike the more adult Lord of the Rings books, The Hobbit was a simple children’s adventure tale. The source material’s more fantastical nature definitely lent itself to making these new movies more heavily stylized, something that does come through at times, particularly in the overwrought features of new characters like Radagast the Brown and many among the dwarf company. The Lord of the Rings movies weren’t without their comic relief, but you weren’t likely to see a scene like this in them:

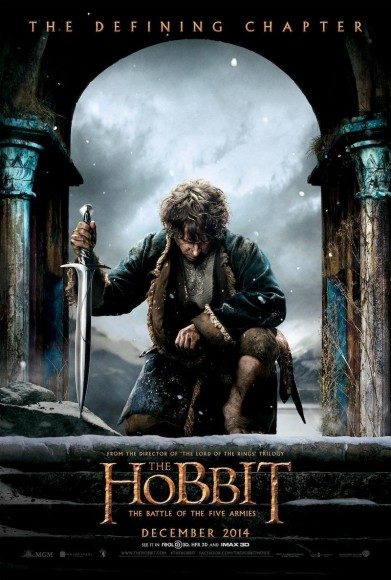

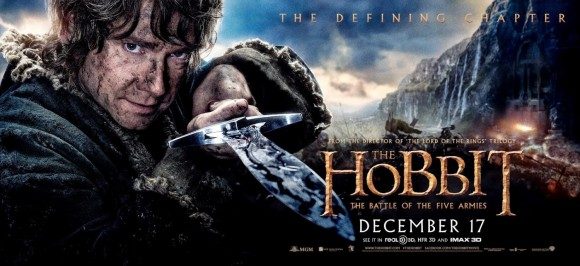

But it doesn’t seem like Peter Jackson was ever particularly dedicated to pursuing this more fantastical direction. Instead, he routinely fell back on the more dark and gritty style of The Lord of the Rings. Even the Rotten Tomatoes Critic Consensus for this film begins with “suitably grim,” which is decidedly not a descriptor for original novel. The tone of the book was one of whimsy, not of war. Yet the poster art and the ads give the impression of a most sullen and tragic experience.

But even if Jackson decided to adapt The Hobbit into a more adult version to better sync up with The Lord of the Rings, he failed to instill in these new chapters one of the most crucial components to the original’s success: good characters. The original trilogy asked a fairly monumental task from its viewers: keep track of all nine members of the Fellowship, along with a number of key supporting characters who wove in and out of the tale. And yet we were able to do because each figure we encountered had a discernible and memorable personality. Even outside the Fellowship, we knew Gollum, Denethor, Galadriel, and others who influenced the plot, were memorable for their personalities, and were effective at expanding the mythology of Middle-Earth — three elements that are missing in most of the characters throughout The Hobbit.

Although mirroring the group adventure setup The Hobbit (book) took a different approach from The Lord of the Rings (and to all those who are screaming, yes, I know The Hobbit came first). The Hobbit was essentially “Bilbo and the Twelve Dwarves,” with none of his company having any real personality. But it worked. The relatively short tale actually benefited from not building up the individuals of the dwarven company (their names aren’t so similar by accident) since it was about one hobbit’s adventure first and foremost. Bilbo was the focus, and all of the dwarves were secondary to him, even their leader Thorin Oakenshield.

Unfortunately, The Hobbit (films) tries to have it both ways. Thorin and Company are still hard to distinguish without utilizing really generic terms like “wise-ish” and “really fat.” Even Bilbo seems underwritten, with Martin Freeman’s terrific performance doing most of the heavy lifting. In a straight adaptation of the book, this wouldn’t be a problem, but at nearly nine hours of movie runtime, we need an emotional connection to hold on to.

Yet instead of allowing the dwarves to come into their own to carry the movies, Jackson takes another approach. Similar to one of the most common complaints of the Star Wars prequels, The Hobbit puts exaggerated emphasis on the characters we already know from the first trilogy (none of whom should have any real impact on the conclusion of The Hobbit) rather than using the time to explore the new crew. More time with Legolas! More time with Galadriel! More time with Saruman! As much as we like seeing Ian McKellan as Gandalf, is it really worth it if his side quests add nothing to the story? (Not to mention the constant Sauron foreshadowing. Understanding that he’s coming does not add weight to a battle in which he has no part.)

The new, non-dwarf characters fare no better. Evangeline Lilly’s created-for-the-film elf character Tauriel seems to exists solely so she can provide a love interest to the dwarf Kili, who seems to only get a subplot so that Tauriel has a love interest. But this fails because instead of making us ‘ship Kiliel (or should it be Taurili?), it only calls attention to how underdeveloped the rest of the dwarves are. It’s nice meeting another member of the wizarding community, but all Radagast the Brown does is speak nonsense and have poo in his hair. Eventual dragon-slayer Bard now has a family he wants to protect and a legacy he wants to uphold so that gives more depth to his character than his role in the book of “random guy who kills Smaug.” But at the end of the war, will he really be anything more than “random guy who kills Smaug?” Meanwhile Beorn, who is a relatively interesting character from the book, is severely underutilized. Hopefully, he bears it up for the third go-around.

While many of these people acted “between the pages” of The Hobbit in the expanded literary universe, there’s a reason why the appendix is non-essential. This issue creeps into pretty much all of the subplots and sub-subplots present in the first two films; instead of adding depth to the story, the universe, or the characters, they just feel like time wasters. The Hobbit trilogy presents a kind of circular reasoning where for the trilogy to exist, it’s okay to add filler to warrant a movie’s ridiculously long running time. But that doesn’t excuse the filler; it only calls into question the need for the increased running time.

So without characters to feel for, what will be our connection when we finally get to the 40-minute battle of the five armies? With Lord of the Rings, it was more than Sauron’s forces versus the forces of good; it was about seeing numerous characters reach the end of their own personal arcs. Legolas and Gimli overcoming the long-standing dwarf/elf feud by engaging in friendly competition of arrow versus ax. Aragorn achieving his destiny by becoming a leader and giving his Braveheart speech. King Théoden of Rohan regaining his independence and his honor. And beyond all that, it was knowing that every single one of those people would lay down their lives for the off chance that Frodo and Sam (who could already very well be dead) could finish their quest to save the world.

What will we get when The Hobbit climaxes? Having Bilbo, our core link to the story, knocked out about 2 minutes into it? (It’s canonical.) Legolas, Thorin, or Bard doing yet another, albeit worse, Braveheart speech? A battle among five armies that haven’t already been meaningfully established? Watching people lay down their lives so that a bunch of dwarves can get gold? The only real character arc to wonder about is whether Tauriel and Kili will lead to the Middle Earth equivalent of Loving v. Virginia .

It’s obvious that Peter Jackson has great reverence towards Tolkien’s works and genuinely loves the ability to play around in Middle-Earth. This feeling has kept The Hobbit from falling to the depths of the Transformers films or the Star Wars prequels, with Michael Bay and George Lucas alternating between complete apathy and a palpable dislike towards the worlds they created. But liking the scenery and the effects is great for a The Art of … book, not a nearly 9-hour movie franchise. Without the emotional connection, which can only happen through characters, the film becomes just another oversaturated effects extravaganza, which unfortunately places it closer to those two franchises than to the original Lord of the Rings or Star Wars.

In the book, Bilbo’s return to the Shire was necessary but bittersweet. He liked once again being able to sit by the fire, but even he recognized that there was something disappointing about the adventure of a lifetime being over. Ironically, The Hobbit film franchise might produce the opposite effect. Seeing either Martin Freeman or Ian Holm sitting in front of that big red book and quietly musing on life will say far more than an army of a thousand orcs.