Within the context of social or political change, ideology, and discourse, the word “radical” is approached as inherently provocative. Logically speaking, everyone is entitled to think whatever they’d like, no matter how outrageous or banal, making radical ideas essentially harmless. Yet, the concept of radical activism or ideology in public spaces seems to be met as a menacing threat towards poisoning passive society into thinking against the status quo. In an ever-changing and progressive society, it’s important to think about the roles radical thinking plays and how it can be easily exploited unjustly. Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) actively presents itself as radical art while simultaneously exposing its own hypocrisy of bourgeoisie activism, the issues of authenticity in media, and the romanticizing of ideologies versus the ability to put them into practice.

In the 1960s, French students started flirting with the ideas of Maoist Communism, eventually producing their own movement of Maoists thinkers. The idea of Cultural Revolutionary China inspired many not because of its practice, but rather because of its utopic and mythical quality that spoke to their radical desires of the time. As a precursor to the bold and pivotal movements of May 1968, these radical thinkers were outspokenly critical of the French Communist Party (PCF) for being more revisionist than radical. For Maoists, ideologies sprung from a foundation of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist attitudes which called for more radical changes in French politics and society. For the PCF, although identifying as communists, the party was more subtle in their approach, aiming for a peaceful transition towards socialism and maintaining sympathy for the USSR, which held on to its imperialist ties to the United States. What began this split between the PCF and the more radical left, was the Alergian war (1954-1962). While French imperialism was actively protested by the more radical communists, the PCF proved to not fully stand with the National Liberation Front (FLN) in their fight towards independence from French colonial rule. Godard was among those gravitating towards Maoist ideas, and La Chinoise became the visual manifestation of his own intellectual journey towards this notion of a pure communist ideology.

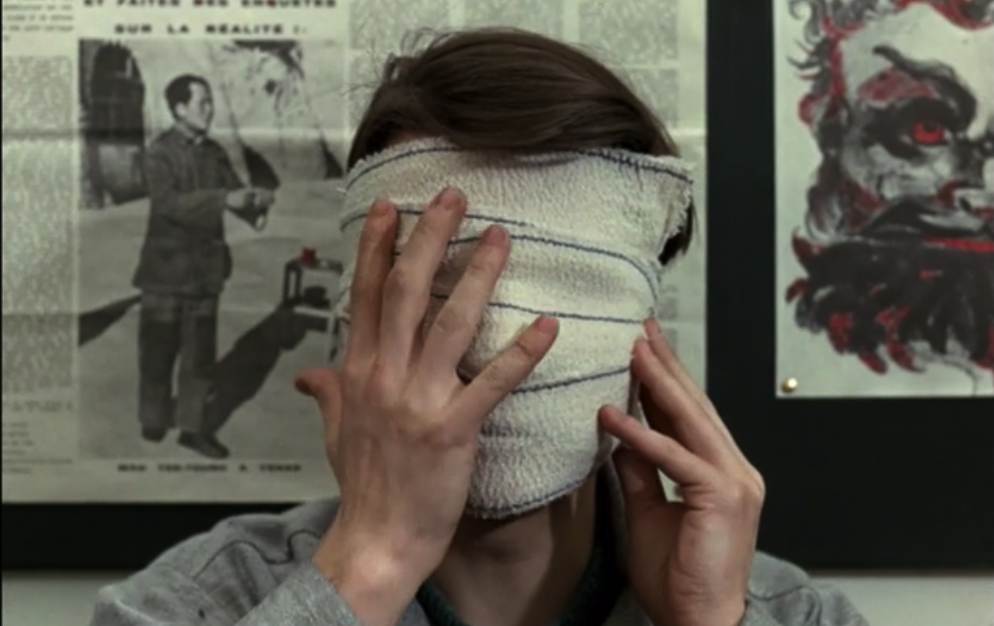

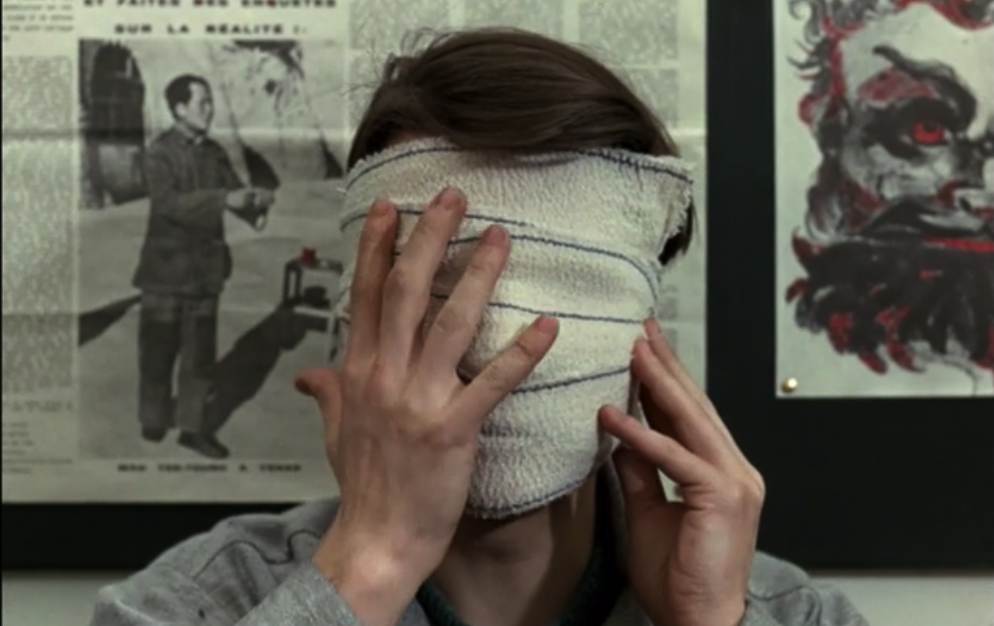

La Chinoise follows a group of young university students using one of their parents’ apartment as a hub for their intellectual debates, research, and communal living. The audience sits among the characters, listening along to their lectures on communist philosophy and watching interviews with each of them that are laced throughout the film. Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Léaud), an actor, is the first to be interviewed. Wrapping a bandage around his face, he reenacts a situation about a protester making a scene about the violence he endured at the hands of Soviet revisionists, gaining the attention of Western journalists, only for them to find out that he was unharmed and only acting. In his interview, Guillaume acknowledges that he is being filmed, addressing the presence of the camera and the crew in front of him. The camera eventually turns upon itself, resulting in an inevitable mistrust of the cinematic apparatus we are engaging with. Henceforth, the authenticity of La Chinoise is established as faulty.

The film appears to claim itself as radical art in its explicit and implicit ties to Brechtian epic theatre and its emphasis on the Maoist ideas of politicizing culture. Epic theatre was a contemporary political theatre movement started by Bertolt Brecht that aimed to create an interactive experience with the audience in order to get them to actively engage with the material on stage as opposed to passively consuming the information. Brecht is shown to be an important figure in La Chinoise with his name brought up frequently throughout the film. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijn) reads his lecture about the history of art achieving the status of being political while Guillaume erases one by one the names of famous writers leaving only “Brecht” to remain. In conjunction with Brecht, the film prioritizes the Maoist value of politicizing art towards educating the people of the revolutionary cause making complex ideas more accessible to the people. Slogans are painted on many of the walls including one that reads “WE SHOULD CONFRONT VAGUE IDEAS WITH CLEAR IMAGES”. The color palette is confined mainly to primary colors: blue, yellow, and most notably red, keeping it simple and clear to the viewer. However, the simple visuals contrast with the complex nature of the lectures, the non-linear narrative, and the mistrust of authenticity that are all inextricable from the film itself making La Chinoise in its entirety an active contradiction, treading on a fine line with hypocrisy.

The most radical of the group is Véronique, played by 19-year-old Anne Wiazemsky, a philosophy student and Godard’s wife at the time. Wiazemsky grew up comfortably in a middle-class household, but while in university she was exposed to the harsh and unfair realities of classism first hand. In her interviews as Véronique, she draws from her real-life experience, speaking about how she was able to identify the “three basic inequalities of capitalism” and her disdain for the Gauliste regime, pushing her to seriously pursue studying Marxism-Leninism.

Towards the end of the film, she meets with philosopher and her real-life professor, Francis Jeanson, played by himself, to discuss the action that must be taken in order to begin this revolution. During the Alerigian war, Jeanson was an outspoken supporter of the FLN, so he was no stranger to violent revolutionary practice. However, this scene becomes a debate stage for the two, as Véronique argues the urgency to begin this revolution with an act of terrorism. The main issue he identifies with her argument is that she is certain that this revolution must be fought for the future, however that future is relative to France which is not the same situation that’s happening in contemporary China. It’s here where the hypocrisy of bourgeoisie radicalism lies in plain sight. When the adopted utopian ideology cannot match in revolutionary practice, the bourgeois radicals are essentially fighting for the sake of fighting. Once the act of terrorism is performed at the end of La Chinoise, we find out that it failed, and the film concludes with everyone succumbing to the status quo of capitalist society.

La Chinoise exposes its own hypocrisy through its contradictory nature that it even recognizes within itself. From the interviews to the narrative, the film seems to actively follow along with the debate that occurs on and off the screen surrounding this idea of the authenticity of this revolution the characters are so desperately ready to begin. For the students, their urgency exerts a passion to fight for the people before they’re even aware, but in reality, it’s an excited and premature leap of faith with no net to catch them.