It’s been a trying set of years for fans of Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai. 2007’s My Blueberry Nights, the director’s first endeavor into the occidental, English-speaking world of filmmaking was titillating but insubstantial, and it was a loooong wait between that and last year’s kinda-historical martial arts epic The Grandmaster. That film delivered, at least according to those that were able to see the international 130-minute cut. Those of us who live under the shadow of the Weinstein Corporation only got to see a truncated version in theaters. And now, we continue to only be able to see that version on Netflix.

With all of that on that table, the way in which the director’s fans have been devouring every scrap of information that’s been released about Wong’s next film, The Ferryman, is telling about the love and respect this man commands. This is a director that inspires fervent, fanatical devotion, the kind of cinematic adoration that is most akin to a longstanding crush with which the heart does, in fact, grow fonder through absence and disappointment. And for many of us, this crush can be traced back to exactly one place: 1994’s Chungking Express. As we prepare ourselves for the director’s next film and celebrate his early masterpiece’s 20th anniversary, it seemed right to take a moment to look back on that first flush of infatuation. What was it that made Chungking Express so special, and how does the film look two decades after the first date?

Chungking Express was, in a rather staggering number of ways, a unique film. Wong was deep into the arduous post-production process of his previous film, the enormous wuxia epic Ashes of Time, when he decided to make Chungking as a sort of energizer and palette cleanser. The film was shot in a blisteringly fast two-month period, with the script being developed on the fly as they shot. When the film came out, it became one of the first Hong Kong films to achieve international fame without featuring a single frame of martial arts in it, and it was the first film to be picked up by Quentin Tarantino (newly appointed to the pantheon of cinema Gods after the explosion of Pulp Fiction) and his Rolling Thunder Pictures distribution company. The smaller, sprier film vastly overshadowed Ashes of Time, the film that Chungking Express was originally supposed to be a momentary diversion from.

But even putting aside all the oddities surrounding the production and release of the film, Chungking Express is a weird movie, starting with the fact that, in a way, it is two movies in one. The film tells two stories, both centered on romantically impaired policemen in Hong Kong, but rather than intercut between them Love Actually-style, the film presents them in sequence. Once the first story is done, it’s gone, and we never see its central characters again. Both stories share some common spaces and side characters, but there’s no last moment twist where everything is connected in some enormously meaningful way. It’s actually played fairly straight: you get two separate and more-or-less-equal stories within the framework of a single film.

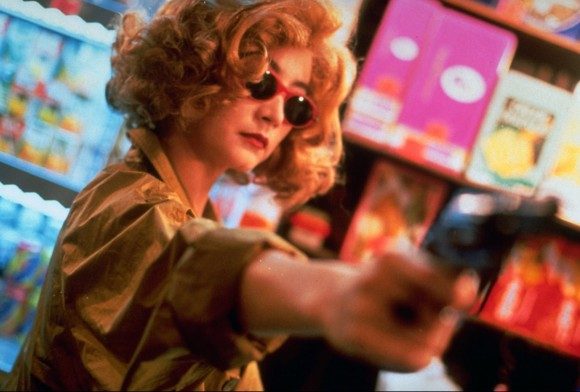

In Chungking Express’s first half, He Qiwu (Takeshi Kaneshiro) is in denial about having been broken up with by his girlfriend, May. He has given himself a one-month span to allow his girlfriend to take him back (his mind works in interesting ways, to say the least) before moving on. As he goes through the final three days of that span, he repeatedly, and coincidentally, crosses paths with an unnamed woman in a blonde wig (Brigitte Lin, in one of her final roles before retiring), a hardened criminal who is in the middle of first organizing and then cleaning up after a smuggling operation. As the two come together, they find an unlikely connection that may help both of them deal with their respective problems.

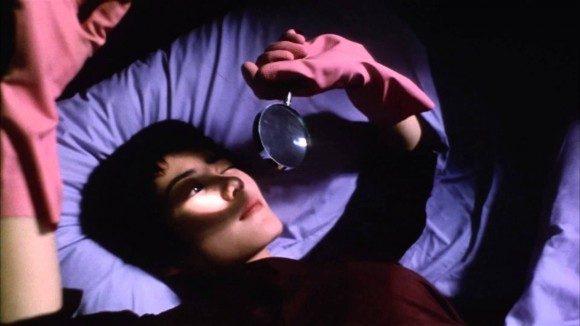

The second story centers on police officer 663 (played by Wong regular Tony Leung, and we never get any kind of identification other than his badge number) whose life is stuck in an aimless rut after a messy breakup. Frequenting a fast-food bar, he catches the eye of Faye (played by Asian pop superstar Faye Wong), the establishment’s explosively quirky but secretly shy new hire. After coming into possession of a key to 663’s apartment by chance, Faye begins sneaking into his home, gradually making improvements to the police officer’s life and replacing the traces of his ex-girlfriend’s presence with ones of her own. Will she succeed in braking 663 out of his self-imposed funk? And will she ever get him to look at her the way he looks at the ghost of his former relationship?

All right, let’s just go ahead and say it: Chungking Express is a movie that should not work. It’s a conceptual mess, assembled from bits and pieces that feel like they came from other movies or were improvised on the fly (oftentimes because they were). Aside from the weirdness of the dual-story model, a hurdle that is too much for many filmgoers to overcome, the film approaches a lot of its storytelling concerns from weird angles. Large chunks of the story are laid out via copious amounts of voiceover from the four main characters. Plots are loosely defined and even more loosely developed, advancing more through the repetition of the characters’ various quirks and daily rituals than through their direct actions or decisions. There’s an old screenwriting adage: in describing the plot of your film, all your scenes should be connected with “because of that” or with “but,” never with “and then.” Chunking Express never got that memo.

Now that we’ve said that, let’s go ahead and acknowledge that the film doesn’t just work – it works marvelously well. The word that always comes to mind with this film is intoxicating, it’s the kind of cinematic experience that takes hold of you and keeps you wired purely on an aesthetic and tonal level. In an odd way, the minimalist and disjointed nature of the plot lets the experience work on a more filmic level, allowing Wong to develop our understanding of the characters through his visuals and music choices as much as through their actions.

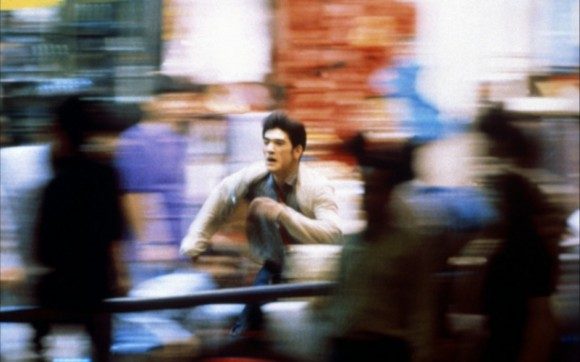

And what visuals they are. Chungking Express is a work of bravura technical experimentation, with all kinds of camera effects and optical tricks thrown into the ring. Practically ever scene features some kind of aggressive touch of impressionistic visuals – handheld camera, jump cuts, blurs, dissolves, reflections, the works. The film opens with a bang, showing a dramatic chase scene between Qiwu and a criminal through a camera shooting at a lower shutter speed than normal. The effect is a blurred vision that splits the difference between moving image and a series of stills, conveying a tremendous sense of speed while still letting us see each distinct moment of the chase. As an introductory statement, it makes quite an impression. About an hour later, the film presents a shot of Faye, in the early stages of her crush, watching 663 drinking a cup of coffee. The two of them move in slow motion, but every other person in the frame moves at an accelerated time-lapse speed. There are plenty of ways to visually isolate two people in the middle of a crowd, but the film’s approach is well off the beaten path. Looking at these sorts of moments twenty years after the film’s release, it’s still difficult to come up with examples of other films that push visual storytelling to this extreme. I can’t imagine how much of a lightning bolt this would have felt like in 1994.

It’s a testament to Wong and longtime cinematographer and collaborator Christopher Doyle that they could pull off an approach this intense over an hour-and-a-half feature. Fortunately they have an unerring sense of how to vary their techniques, and perhaps more importantly when to pull back. (The opening virtuoso barrage of the stutter speed chase is followed by a lengthy phone conversation that is shot through very simple and straightforward series of medium close-ups, for example.) The result is a film that feels relentless without ever becoming exhausting. Perhaps the key to the formula is how down-to-Earth and accessible everything around this visual razzmatazz feels. Wong is playing with the toolkit of someone like a Godard, but you never feel a big academic concern or metatextual point looming in the background. Instead, all of the film’s armament is aimed back at conveying emotions that we’re all too familiar with. Attraction. Jealousy. Longing. Loneliness. It’s a pair of love stories told through the toys of the French New Wave, with surround-sound pop music blaring from wall to wall.

Speaking of the love stories, once you get over the unusual form in which Wong approaches them, the two little tales remain surprisingly effective and touching. The big underlying joke of the first story is that its two characters are essentially from different film genres – she’s from a gritty Hong Kong crime film, he’s from a goofy rom-com. The scene where the two finally meet is as incongruously hilarious as one could hope from the match up: Qiwu, oblivious to Brigitte Lin’s criminal activities and having decided that he’s in love with her at first sight basically because he needs to be in love with someone, dammit, approaches her at a bar and opens conversation with what has to be one of the oddest and most ill-conceived pick up routines ever. The film doesn’t run with this concept as far as something like Cabin in the Woods does, but as the driving engine for what ultimately amounts to an extended short film, it hums along nicely.

It’s the second story, though, where the film really shines. The central conceit of that story is that 663 is so brokenhearted by his failed relationship that he is in a state of functional catatonia, one so pronounced that he doesn’t seem to notice as his apartment undergoes massive renovations around him. It’s exactly as silly as it sounds, but it allows for a wonderful series of gags that escalate nicely as Faye keeps upping her game and working to break him out of his daze. Just when things are getting to the point of being too inane to be effective, the film tips its hand and you realize that something more complicated has been going on between the two characters. The result is less viscerally funny than the first story, and definitely more sentimental, but it’s also more poignant and emotionally eloquent.

Seeing the film again in a post-Zooey Deschanel world, it’s impossible to not notice that Faye fits the mold of the manic pixie dream girl so impeccably that you kind of feel she would have been the trope codifier if the film had come out in a different intellectual context. Gorgeous girl with more quirks than you can name who makes it her mission in life to break the brooding man out of the pallor of a failed relationship? Oh, it’s all there. In spades. And yet Chunking Express never feels like it’s descending into the realm of male wish fulfillment or aimless female characters; the relationship between 663 and Faye feels very genuine and multi-faceted. Perhaps what helps the film avoid these pitfalls is that, much like its spiritual successor Amelie, the relationship between the two is ultimately shown to be mutually healing and the most relevant character arc ends up being her development. The final moment that brings them together isn’t a grand, explosive declaration of love; it’s a small moment of mutual empathy, of patience towards the other person in the room.

Writing during the film’s U.S. theatrical run in the mid-90’s, Roger Ebert closed his review of the film with the following statement:

Wong is […] an art director, playing with the medium itself, taking fractured elements of criss-crossing stories and running them through the blender of pop culture. When Godard was hot, in the 1960s and early 1970s, there was an audience for this style, but in those days, there were still film societies and repertory theaters to build and nourish such audiences. Many of today’s younger filmgoers, fed only by the narrow selections at video stores, are not as curious or knowledgeable and may simply be puzzled by “Chungking Express” instead of challenged. It needs to be said, in any event, that a film like this is largely a cerebral experience: You enjoy it because of what you know about film, not because of what it knows about life.

Perhaps the biggest change for Chungking Express in the past twenty years is less in the way that other films have managed to imitate it’s successes or excesses, but in the way that we have become more literate and better equipped to deal with them. Looking at the film again after reading the review, I was struck by how much I disagree that the film is an intellectual experience. It uses the tools the film intelligentsia, but its concerns are earthy and visceral. It’s a romantic comedy told through the techniques of the art film world, and maybe now, after two additional decades of filmic experimentation and exposure to various corners of the cinematic world through the online community, we’re ready to have the film reach our hearts without going through the intermediary of our brain.