It is exceedingly rare to find a great artist, one who produces magnificent works of art in volume, who does their great work at the start of their career. Don’t get me wrong – there’s a lot of sad stories of artists who roar onto the scene with their sole spark of “I see dead people” lightning, but for most of the truly gifted, there’s usually a marked pattern of inspired-but-unrefined formative years, enlightened middle age, and degraded-yet-defiantly-experimental twilight. Which is not to say that just because a work isn’t operating at the zenith of an artist’s powers it can’t be an entertaining of illuminating experience. Latter day works, like previous B-Side subjects Bunny Lake is Missing or F for Fake, can be, for all of (or maybe because of) their sense of restless boundary pushing, particularly eloquent about the particularities that make an artist unique. And, likewise, early works can be a chance to see an artist operating in an interesting primal state – less refined, sure, but also less restrained.

The Pirate, released in 1948, is not Vincente Minnelli’s finest hour. It’s not as unflinchingly incisive as The Bad and the Beautiful. It’s not as tonally nimble as his make-you-laugh-all-the-way-to-the-moment-it-moves-you-to-tears masterpiece Father of the Bride. It’s not as dizzyingly impressionistic as An American in Paris, not as surprisingly layered as The Bandwagon, not as psychologically engrossing as Home from the Hill. It’s not even the best early period Minnelli, an honor that still goes to the emotional opulence of Meet Me in St. Louis. There’s still, however, something magnetic about this film and the gleeful energy that pervades it.

Where exactly that energy came from is a bit hard to tell, as most of the surviving stories about the making of this musical paint a picture of a rough affair. It was the fourth time that Minnelli was working with then-wife Judy Garland, and it may have been the one time too many. The film’s production was riddled with arguments between the couple and various issues resulting from Garland’s burgeoning addiction to prescription drugs. Reports say that Garland missed over half of her scheduled shooting days, leaving Minnelli and her co-star, Gene Kelly, to furiously dance around her availability in order to keep the film’s various plates spinning. A valorous effort, but one that didn’t win over moviegoers in the 40s. In spite of some generous reviews, The Pirate’s returns were dwarfed by the high costs of its production, and it was one of the least successful of MGM’s grand musicals.

And now, as is getting to be customary in this series, it is time to clarify that The Pirate is nothing short of a masterpiece in filmmaking. On-set problems or no, and regardless of audience reaction at the time, this is one of the best times that you will ever have with an old Hollywood musical. And if it doesn’t rank amongst the tiptop of Vincente Minnelli’s personal output it’s just because, holy crap, did you see what the competition is? If someone other than Mr. Technicolor Perfection himself had made this, chances are that it would be the undisputed peak of their artistic career.

The Pirate is set in the small Caribbean village of Calvados somewhere in the storybook age of gallant sailors and swashbuckling corsairs (you kind of get the feeling that somewhere around here, perhaps just a few feet offscreen, Errol Flynn is having one of his adventures). Young Manuela Alva (Garland), in the fine model of a Proto-Disney Renaissance Princess, lives a sheltered life while dreaming of, you guessed it, adventure in the great wide somewhere. Raised by her conservative, religious aunt and about to be married to the respectable but rotund mayor of the village, Manuela fixates on the idea of being swept away by Macoto, a legendary pirate whose exploits she’s followed since she was a little girl.

Days before her wedding, a troupe of actors sails into town, led by charismatic, womanizing Spaniard Serafin (Mr. Kelly in what has to be the most flamboyant role of his career). Womanizing, that is, until he bumps into Manuela, with whom he falls in love at first sight. Unfortunately for our would-be Casanova, Manuela is not that desperate and rebuffs his advances. As luck would have it, though, he happens to catch wind about the girl’s obsession with “Mack the Black” (i.e. Macoto) and concocts a scheme worthy of the most insane of screwball comedies:

- Step 1: gather a large crowd in the town square

- Step 2: announce that you are, in fact, the legendary brigand king of crime himself, returning to active piracy after a spell of incognito retirement, and demand that the town hand the young Manuela over

- Step 3: we’ll get there when we get there

Now, if the thought occurs that pretending to be what basically amounts to public enemy number one might not be the most… prudent long-term strategy when it comes to staying out of jail, well, yes, that is a valid concern. It’s not long before the authorities are on hand, feverishly working to apprehend the wanted brigand. Even worse, it turns out than none other than the real Macoto, who happens to actually be enjoying a spell of incognito retirement in Calvados, is on the premises, and none-too-thrilled about the attention that this imposter is drawing. Soon enough a deadly game of high-stakes roleplaying is underway, with Serafin, Manuela, and Macoto all trying to out-act everyone around them, lying about who they are, what they want, and whom they love. It’s great fun.

Running through the spine of the storybook romantic adventure is a set of wonderful songs composed by Cole Porter. There are, however, fewer songs than what you might expect from a full-fledged MGM extravaganza – only four full numbers (two of which get brief reprises) and a modestly lengthy ballet sequence that illustrates a character’s fevered dream. Still, the numbers that are on hand are all whoppers, perfectly suited to Kelly and Garland and perfectly illustrative of their respective characters.

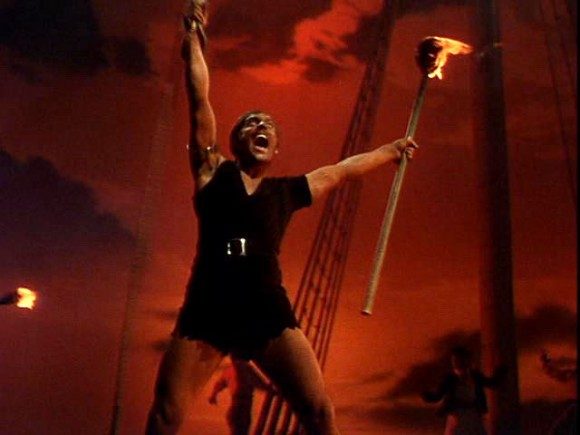

Consider, for example the film’s first big number: the Kelly powerhouse “Niña.” Interestingly, it comes relatively late in the film, not starting until the film’s 14-minute mark. This is less of a blunder than a tactical strike: we spend the first quarter hour of the film learning about Manuela’s upbringing, her stringently religious caretakers, her bore of a husband-to-be, and her dreams of a more exciting life. When Kelly rolls into town at the head of a group of performers with a five-minute foot-tapping musical extravaganza, he turns all of that on its head. He’s a breath of fresh air, for the audience as much as for the characters in the film.

It also helps that the musical numbers are the works of, you know, geniuses. Minnelli and Kelly would come to be two corners of the triumvirate that would define general audiences’ ideas of the classic Hollywood musical (with the other corner belonging to Fred Astaire). The two of them would go on to make An American in Paris a few years later, but this, their first collaboration, established the extraordinary artistic chemistry between the pair. Minnelli has long been known as a master of the tactile, earthy dimensions of film, a director who achieved levels of expression through tools like production design and color coordination that most directors wouldn’t even dream about. Kelly is the great innovator of cinematic dance, possessing the intellectual heft to conceive unbelievable choreographies and the physical might to fulfill their punishing demands. The two were known as exacting perfectionists, but the interplay between their styles is the stuff of cinematic dreams. Watching “Niña” and seeing Kelly tearing through the tiny Caribbean town, speed-seducing every woman that crosses his path, is almost like watching a bravura spectacle of cinematic one-upmanship. Kelly will do some incredible backflip, but then something will shift slightly in the background and some amazing color design will fall into place, but then the dancing will shift from the street to the balcony and soon he’s on the rooftops; but wait, because the camera just shifted to catch this new graphic element that guides your eye towards this new woman that just walked in… on and on it goes, and by the time it’s over Minnelli and Kelly have thoroughly established their mastery over the film world.

What really makes The Pirate into something special, and what makes it so that you don’t really notice how few big numbers there are while you watch it, is that this level of coordination and musicality seeps into every single scene in the film, musical or otherwise. Once Serafin puts his plan into motion and the hurricane of lies begins, every facet of the movie takes on this quality of theatricality and performance. There’s a point in the film where Kelly and the real Macoto, who both know the truth about each other, are talking to each other in a room full of people, none of whom are in the know. The way that coded and layered statements fly between the two has a rhythmic cadence to it, a rat-tat-tat sort of quality that makes it feel astoundingly musical for a piece of dialogue.

Another example from later in the film: Kelly and Garland are alone in a grand room when he makes the grievous error of upsetting her. She proceeds to throw everything that isn’t bolted down at him while he tries to stammer through an apology while dodging china and pieces of furniture. They tear the room apart, but it’s the most graceful and well-arranged fight that you will ever see. An appropriately sized jar is always within Garland’s reach. A painting smashes over Kelly’s head at just the right syllable. They’re not dancing, but they might as well be. There’s as much coordination and choreography in that space as there was in the “Niña” number.

Oh, and she spanks him with a sword. In case it’s not abundantly clear yet: you need this movie in your life.

Perhaps that’s the key to what makes The Pirate such an engrossing experience: it’s not just a musical. It’s less about music than it is about performance, both in its content and in its form. The story is all about a very particular performance (Serafin and his troupe on their stage), but then the playacting moves out to places where it’s not supposed to be – into people’s lives. Likewise, The Pirate begins with the operational premises of a standard musical (there are these numbers where people are going to sing and dance) but then the qualities, the staging, the rhythms of the musical invade the rest of the film. It all comes to a conclusion that is both a mile-a-minute and intricately layered, with all the deceptions being parsed out in an extravaganza that brings together everything from hypnotism to literal gallows humor to tap dance to a musical ode to, of all things, clowns.

As a statement about entertainment and entertainers, The Pirate is not as sophisticated as some of Minnelli’s later films. The dark side of performance and lying, their destructive power, and the price to be paid even by the best of performers and liars is but a remote threat in this film while it is laid out in full in films like The Bad and the Beautiful and The Bandwagon. But there is still something of great meaning contained in this simpler (and I use the term loosely) film, a wonderful defense of artists and the way that they, even if they do so by dealing in untruths, can help us to realize what is really happening in our lives, what we really need or want. Fortunately for us, Minnelli, Kelly, and Garland wrapped up these ideas and grand statements not in a pondering think piece, but in a breathless work of furious comedy. In other words, they remembered the advice dispensed by their film’s final song:

“Be a clown, be a clown,

All the world loves a clown.

Act a fool, play the calf,

And you’ll always have the last laugh.”