Few directors’ catalogues are as full of candidates for our Director B-Side series as Orson Welles. There is no other filmmaker who has had such an enormous impact on the art form and had so many of his films buried by the sands of times. There’s many a cinephile that has never moved past the Holy Trinity of Citizen Kane, The Lady from Shanghai, and Touch of Evil, ignoring the underseen gems that make up the rest of Welles’s filmography. So when given a chance to shine a spotlight on just one of them, which one do we choose? Do we go with the restrained, almost Hitchcockean thriller The Stranger, the one film that Welles was forced to bring in on time and under budget? Or his nightmare adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, a masterclass in how to use camera angles and set design to create terror? Or the brooding majesty of Chimes of Midnight, one of the few Shakespeare adaptations that feels like it’s adding something to the theatrical tradition rather than running behind it to play catch up?

All would have been fine choices, but there’s one diamond in the rough that outshines them all. For the most obscure entry in the catalogue, for the most devious, the weirdest, the most Orson-Wellesian of the bunch, you have to go straight to F for Fake.

F for Fake holds a few distinctions in the Welles canon. Released in 1974, F for Fake is the last film that the director completed before passing away in 1985. It wouldn’t be the last artistic endeavor that Welles embarked upon (and a partial account of some of his most high-profile unfinished productions can be found in our Terry Gilliam editorial), but this was the last feature length project that he saw through to completion. It’s a project made by a different man than the one that made his most famous films. This isn’t the maverick wunderkind of Citizen Kane or the bitter, exiled genius of Touch of Evil. The mind behind this film is no less boundlessly creative than the one that made those films, but the proceedings are less ponderous and overwrought. There is an airiness to the manic experimentations of this film, as if Welles was making every insane decision with a shrug and a “I’ve had worse ideas” grin on his face. For a director who spent the majority of his life trying to assert his own worth, F for Fake often feels like it was made by Welles and for Welles, as if the only person he was trying to prove anything to was himself.

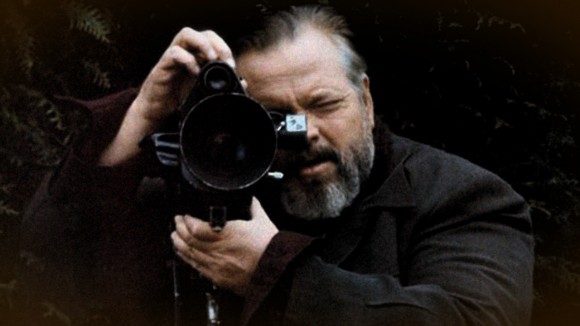

It is also Welles’s only feature-length documentary film, and oddly enough, not a film that was completely his own. The exact details of how, and in what shape, the film came into Welles’s possession are murky, but the project started out under the leadership of Francois Reichenbach. At some point, the director handed control over to Welles, who shot new material, recut the entire film, and turned the project into a much more ambitious animal. Looking at the finished product, it’s possible to hazard an educated guess at what parts were shot by Reichenbach and which by Welles, but it’s ultimately not important. Welles’s influence over the completed film is so absolute that you never question who the controlling entity behind the film was.

So what’s the story? F for Fake is a documentary about lies, forgeries, deceptions, inventions, fibs, and all manner of mendacious deceptions. It’s a film about conmen and liars, and what happens to the “truth” of men who dedicate their lives to falsehood. The French title for the film, Verites et mensonges, more accurately translates to “Truths and Lies,” a statement that cuts more deeply into the film’s heart than its official English title.

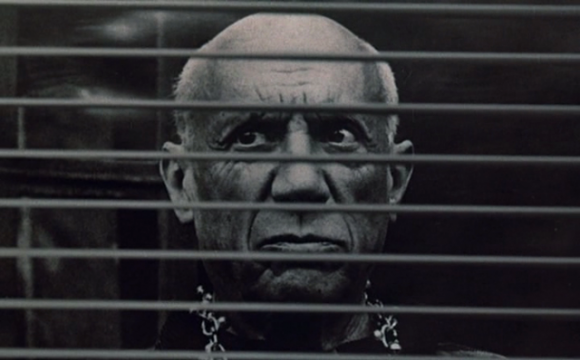

The film is organized around three main stories, presented (more or less) in unified blocks. The first section deals with Elmyr de Hory, arguably the 20th Century’s most prolific and successful art forger. The second talks about de Hory’s biographer, an American writer named Clifford Irving. Irving achieved notoriety after writing a book about reclusive millionaire Howard Hughes that was later publicly revealed as a fabrication. The third tale is… something different. It’s a more involved story, and while I won’t spoil the details, I will say that it involves paintings, forgery, beautiful French beaches, Pablo Picasso, Welles’s girlfriend, and, yes, a whole bunch of fakes. Along the way, the film takes a few detours to tell stories about street magicians, filmmakers, Howard Hughes, the War of the Worlds broadcast, and Orson Welles himself.

If it seems like that’s a lot of ground to cover in 85 minutes, well, it is. The film moves not linearly, but free form, jumping from one storyline to the other, then to a tangent, back to the second, then to the first, then back to the tangent, all in a breakneck stream of consciousness style. It’s less concerned with telling a story or making a point than it is with ruminating on the different aspects of a central question, using its nonfiction subjects as illustrations of its various ideas. F for Fake is often called a cinematic essay, but I think that more than an essay the film feels like a filmmaking jam session, like the blocks that make up the film are different meditations on a theme or riffs on an idea.

And what’s that central unifying idea? Largely, the film seems obsessed with the line between lying and artistic creation. Why, the movie seems to ask, do we celebrate one kind of liar then turn around and condemn others? During one of the film’s side adventures, Welles recounts the story of a South American man who heard about his War of the Worlds broadcast, recreated it in his own country, and was promptly thrown in jail for inciting panic by the local authorities. “I didn’t go to jail,” Welles recalls glibly, “I went to Hollywood.”

So the film’s narrative structure is unusual, a playful exploration of thoughts that is more interested in asking questions than it is in giving any kind of definite answers. It’s in the film’s form, however, that its true prowess shines through. Welles throws all kinds of crazy experiments at the wall with this one, moving so quickly that he doesn’t even stop to see what sticks. Separate interviews are intercut so it looks like interviewees are answering each other’s questions. Welles himself narrates large sections. Sometimes he appears onscreen, offering up a theory about how something could have happened, only to have some authoritative figure pop up and knock him down. Gaps in the available footage are filled with still images, pictures, and old stock footage. In a triumphantly creative sequence late in the film, Welles recreates a scene involving a mysterious woman and Pablo Picasso, depicting the painter’s side through a rapidly cut succession of pictures and the artists’ self-portraits.

These techniques might not seem all that revolutionary now, but imagine how they would have come off in 1974. It’s common to call Citizen Kane a film ahead of its time, a before-and-after moment that divides when narrative films went from looking antiquated to feeling modern. If anything, F for Fake is much more deserving of that distinction, a documentary that feels decades ahead of its contemporaries and closer to the impressionistic non-fiction films we’ve seen in later years. Just try watching F for Fake and Hearts and Minds, 1974’s best documentary feature according to the Academy Awards, back to back. Hearts and Minds remains a stunning work of investigative journalism, but aesthetically it feels like a lumbering dinosaur. It feels like the only thing keeping F for Fake from playing on MTV is its subject matter.

And that’s what makes this film such a joyous experience to dive into – it is such an energetic and endlessly playful film. There’s even one larger experimental conceit that blankets the entire film, one that isn’t unfurled until the final moments and which I would not dare to reveal here. Suffice to say that if the thought struck you that it’s a bit weird that Welles would choose to make his odyssey about liars and lying a documentary, the one kind of film that is, at least nominally, bound to not tell lies… well, it’s not a bad thought to have. The truth, as with everything the film discusses, is a bit more complicated than that, and by the time the film is done it feels about as thorough a statement on Welles and his artistic oeuvre as anything he ever created. The film opens and closes with him performing magic tricks, although the second one is on a much bigger scale than the first. If we had to leave Orson Welles somewhere, it’s not a bad image to do it.

There is a small section in the middle of F for Fake where the film slows down. Just as the unrelenting parade of smash cuts and quick flashes is about to become too overwrought, Welles slams the brakes, and cuts to a four-minute sequence centered on the Chartres Cathedral in Southern France. We get gorgeous shots of the majestic cathedral as Welles waxes poetic on its beauty, speculating on how, in spite of our flaws, there might be some hope for us if we are able to produce something as artistically meaningful as that building. It’s an absorbing section, but if feels like something from a different dimension compared to the goings-on around it. What’s it doing in this film? Maybe Welles knew that we would need a moment of earnestness to break up the wild whirlwind of deceit. Or maybe he knew that he wouldn’t get another film to put it in.