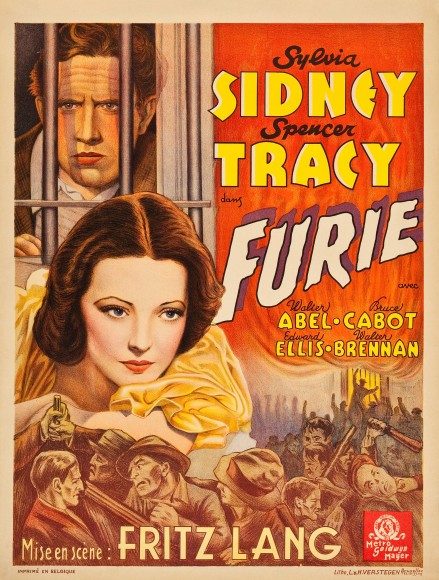

Fritz Lang’s 1936 film Fury is a piece of art that seems to leave a lot of people unsure of how they should interact with it. Upon its initial release the film was a hit for MGM, but in subsequent years it seems to have been relegated to the footnotes of the film history. It’s often only talked as “lesser Lang,” a purely serviceable film that’s only remarkable for being the director’s first film in the United States. When someone does talk about the film, the conversation betrays a certain degree of hesitance about how to navigate it. It’s a difficult film. It takes strange turns. It’s politically unsure about where it stands. It’s a morally confusing work. Seen from a certain point of view, Fury is all of those things. It is also one of the most artful acts of cinematic manipulation you will ever see.

Few directors’ careers are as varied or storied as Fritz Lang’s. Like John Ford, here is a man who navigated pretty much every major step of early cinema’s development, and who made masterpieces at every point in that trajectory. Lang started making silent films in Germany in 1919 and didn’t stop directing until 1960. He was one of the main proponents of the German Expressionist movement. He made what might be film’s first science fiction epic with 1927’s Metropolis. He handled the transition into talkies adroitly, producing one of early sound filmmaking’s masterpieces with the crime thriller M in 1931. After moving to America in the mid-thirties, he began working for the studio system and became one of Hollywood’s leading makers of film noirs. Even as he entered his sixties and seventies he remained a magnetic figure, stretching the ideas of how uncompromisingly violent Hollywood films could be with works like The Big Heat and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. This is a man who saw film grow up around him, and who had a lot to do with that growth personally.

Fury was made at the period of greatest change in Lang’s life. A few years earlier the director had been one of the leading filmmakers of Germany, only to find his career upturned by the rise of the Nazi party. His 1932 film, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, was seen – correctly – as containing anti-fascist sentiments and calls for public resistance to the emergent party. According to one of Lang’s so-good-who-cares-if-it’s-not-completely-true stories, he was called into Joseph Goebbel’s offices to be informed that Mabuse was being banned and to be offered the job of head officer for the now Nazi-controlled film studio UFA. Lang, who was of Jewish ancestry on his mother’s side, asked for time to consider the offer and fled the country that very night, leaving his estranged wife behind. (Don’t feel too bad for her – she joined the Nazi party and got a lot of work making propaganda for them.) After a short stint in France, Lang found himself in the States and making films.

Self-exiled from his own country, making films in a new language and with a new production system, still relatively new to talkies, ideologically betrayed by his long-time partner… it’s safe to say that Lang had some stuff he needed to work out. And all of these concerns coalesced and came out in a little film called Fury.

Fury opens on such an unassuming and genteel note that for half a second you wonder if you accidentally put on the wrong film. Both overseas and in the States, Lang was known as a purveyor of darkness. His films are full of crimes, murderers, hysteria, and violence. What’s the first thing that Fury gives us? A beautiful bridal bedroom, complete with gorgeous floral arrangements. After a few moments of the blissful image, the camera moves to reveal we’re looking at a window display for a department store. Watching the display from the other side of the glass are Joe Wilson (Spencer Tracy, shockingly young in one of his first leading roles) and his fiancée, Kathy (Sylvia Sydney). They’re madly in love but dirt-poor, both staring down dead-end jobs and looking at this perfectly composed bedroom that’s mere inches from touch but millions of miles away from their lives.

The first chunk of Fury follows these two characters in a way that feels very reminiscent of a romantic melodrama. They want to get married, but they want to do it right – buying a respectable home and living a wholesome life. They’re both worried about their jobs, and Joe frets over his two brothers, who are as poor as he is but more inclined towards disreputable lines of work. When Kathy gets offered a higher paying job in a nearby city the couple reluctantly part ways, vowing to be reunited as soon as they have the means to do it. It’s all well-done and very affecting – Tracy and Sydney have great chemistry and do a good job of selling how in love these two are – but it feels odd coming from Lang. It’s the sort of fare you’d expect from a Frank Borzage or a Douglas Sirk.

Things quickly look up for our heroes, though. They both come into some money through their hard work, and Joe drives off towards the city to reunite with Kathy. On the way, he crosses through a small town and gets stopped by a local cop. There are some coincidental connections between Joe and a suspect in a recent crime that has shaken up the community – the kidnapping of a small child. It’s probably nothing, but he better come to the station and answer some questions just to play it safe.

And that’s when Fury begins to slowly take a macabre turn. One of the sheriff’s deputies mentions to his wife that they may have someone who is connected to the kidnapping. When she tells the story to her neighbor, Joe becomes a prime suspect in the case. Five minutes later he’s a man who was seen with the kidnapped child. By the time it reaches the local watering hole, the story is that the police have captured the mastermind behind the kidnapping and found $10,000 of ransom money in his car. And when an idea materializes, practically out of the ether, that Joe is about to get in touch with his fat cat big city lawyer and get off scotch free, the notion that the town should administer justice before this villain can slip away starts to gain some traction.

Suddenly, without any moment when you can detect the discrete transition, the film has grown some teeth. It’s no longer a romantic melodrama about these two lovable can-do Americans – it’s a suspense piece about this powder keg of a town that Joe had the misfortune of getting stuck in. Things develop at an alarming rate, and soon every passing second feels like the tick of a time bomb. How long before this town explodes into violence? Will the sheriff and his men be able to fight off the mob before they lynch Joe? And will Kathy, who by chance has managed to discover Joe’s situation, be able to reach the town in time to stop the madness? Let the nail biting begin.

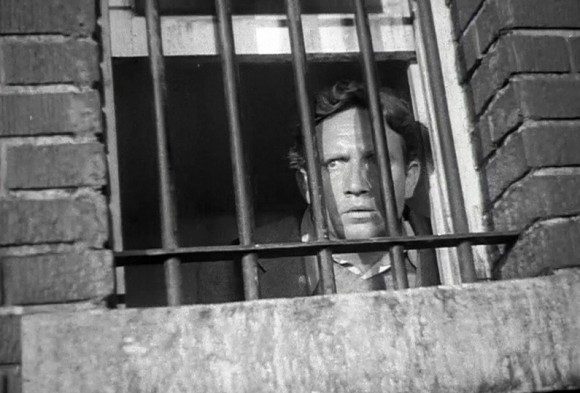

And then – just when you think you’ve figured out what’s happening in Fury – the bottom falls out. The mob does attack the police station, and, with Joe still inside, sets the building on fire. Kathy arrives just a moment too late and gets to see the blazing inferno consuming her fiancée. Joe, our nominal protagonist, dies…

… or so it would appear. Joe actually survives the fire, but decides to let the world continue thinking that he perished so that the men and women who formed the mob that lynched him can be tried for the crime. As far as he’s concerned, these people murdered him; the fact that he miraculously survived does nothing to exonerate them of their actions. Taking a leaf from the Edmond Dantes manual, Joe sets his sight on revenge, planning to hijack the trial from behind the scenes and ensure a guilty verdict. Only then has Fury finally begun in earnest.

If it seems like I’m spending too much time explaining the machinations of this film’s plot, I apologize, but I really need you to understand the way that Lang maneuvers the audience through these sharp turns. Never fear – by the time that the trial of mob members begins the film is less than halfway over, and there are plenty of twists and surprises still to come. It’s that evolution, however, of romantic melodrama to pulse pounding suspense film to cold-blooded revenge thriller that’s the key to understanding this film.

Here’s the thing about Fury – it is ultimately what used to be called a “social problem” or “message” film, a movie that was designed to present a problem that was plaguing society and deliver some sort pronouncement on it, usually a morally upright one. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is about as definitive an example as you’re going to get of this subgenre. Lang’s social problem is lynching (which was an enormous problem at the time the film was made) and his message was ironclad: “justice” enacted in the grips of passion and fury is nothing but murder.

Some modern critics have raised their eyebrows at the fact that Fury was made with all white-cast while lynching was predominantly a problem in African American communities. But in a way, the lack of a racial component (within the context of film’s narrative) works to universalize the problem. Racism and prejudice deserve to be demonized, but it’s easier for an audience to distance themselves from evil deeds being depicted on the screen if they can be seen as stemming from discrimination or other endemic social ills afflicting only a subsection of the populous. “Racist people can be horrible,” doesn’t cut quite so close as, “People can be horrible.” The idea that the townspeople’s thirst for vengeance is set off by its own trauma, by a horrible crime committed against a child, makes their violence harder to avoid. That’s something that everyone can relate to. No one is immune to that kind of madness.

These ideas, potent and unsettling as they are, could have been enough to carry Lang and the rest of the filmmakers to an affecting piece of work. It would have been so easy for him to make a version of Fury where Joe perished in the prison fire. That film would have been thrilling and engaging, with the lives of the mob hanging in the balance as Kathy and the prosecutor tried to make the charges stick. It would have even been thought provoking in its presentation of everyone’s innate capacity for evil through its depiction of the mob. They’re regular folks who slowly and believably fall into a very dark place. No one shows up twirling a moustache or adjusting a black hat. All the townspeople are relatable (some are even likable) until they go one step too far.

But by adding the final layer of Joe and his plot, Lang creates a much more complicated picture. In a way, Joe emerges as the real villain in Fury, a person who is committing a much more calculated attack than anything that was done to him. If the kidnapping of the girl brought out fiery, vengeful passion in the townspeople, their own crime created a much colder, darker hate in Joe. “I’ll give them a chance that they didn’t give me,” he intones. “They will get a legal trial in a legal courtroom. They will have a legal judge and a legal defense. They will get a legal sentence and a legal death.” It’s a chilling speech, but it doesn’t seem to completely gel with the way the film was condemning the town for taking the law into their own hands fifteen minutes earlier.

Which doesn’t mean that while the film is doing anything other than rooting for Joe’s plot. This is the great manipulation that lies at the heart of Fury. The film builds both an intellectual case and an emotional one, and they are aimed in completely opposite directions. The intellectual side of the film says, “No one should take the law into his own hands. Period.” The emotional side goes, “How could those bastards do that to poor Joe and Kathy? We’ll see them hang!” There’s a reason why the film opens with fifteen minutes of Joe and Kathy being cute and adopting puppies. (Oh, did I forget to mention that they adopt a puppy? Because they do and it’s adorable.) And there’s a reason why the suspense portion of the film is so high-pitched. Fury works hard to get you invested in its leading couple, and when everything they’ve worked for is smashed apart, it really hurts. The Fury in the title is as much the audience’s as it is Joe’s, and you are very much made to align with and root for his plan as it goes into effect.

This is Lang’s masterstroke. Pointing out that the hysterical mob is acting out on man’s worst nature is not a sophisticated or complicated affair. But to turn that process on the viewer? To put the audience through a form of trauma, drive them to fury, and present them with a plan so well thought out and full of poetic justice that it’s irresistible, only to yank back the leash? That’s what Lang wanted to do. To tap into a place of irrational fury and then go, “And if anyone of you was thinking that this was a good idea, you need to go home and think long and hard about this.”

I’m not going to reveal how Fury ends or how the film ultimately resolves the divide between its emotional and intellectual sides. It is easy, however, to see how many people would find this to be a difficult film, or even an irresponsible one. It’s a work that meddles with the emotions of its audience and leads them towards a place that it then reveals to be extremely dark and uncomfortable. Looking back on the film now, it’s almost certainly taking some of its cues from the social upheavals that Lang saw in Nazi Germany, but it continues to pulsate with relevance and vitality even now. Any time a traumatized or unjustly punished person or group begins to seek justice while in the throes of fury, they may meet an emotional landscape like the one depicted in this film. It’s not the most comforting of movie experiences, but it may be worth the trouble to first meet these emotions when they’re coming courtesy of Mr. Lang rather than courtesy of the real world.