As the year comes to a close and the Oscar race heats up, like every year, we’re going to get inundated with biopics. American Sniper about Chris Kyle (played by Bradley Cooper), Selma about Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo), The Imitation Game about Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch), and The Theory of Everything about Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) are some of the bigger ones that already have or shortly will be hitting theaters this year. These biographical films are perennial Oscar favorites and genuine crowd pleasers. There’s just one slight problem – they’re often not that good.

Biopics tend to be fine on a technical level (e.g. acting, production values), but ironically they lack personality. They’re painfully formulaic and conventional, treating their subjects’ lives as a series of greatest hits moments that fail to comprehend or express his or her historical relevance or give us true insight into the subject’s life. The characters hit their story beats like metronomes, but it’s hard to say you leave these movies with a better understanding of who these people were or what they accomplished or why they were driven. A good biopic should treat its subject the same as any regular movie protagonist; “Based on a true story” is no excuse for an underwritten main character or a movie that does little more than tick off a checklist of plot points.

However, some biopics have bucked the trend and created something remarkable that stands the test of time as a flat out great film. A look at some recent alternatives shows that this genre can be genuinely innovative and produce actually good movies.

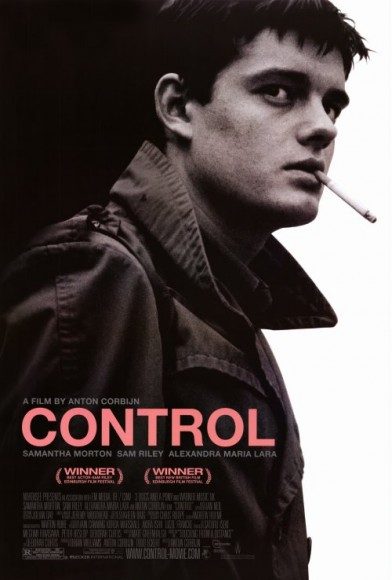

1. Control, Or We’re Talking About Humans Not Gods

The musical biopic tends to be among the most popular in this subgenre. Understandably so, since the producers get a ready-made soundtrack and a person with whom people are at least vaguely acquainted. Unfortunately, these are the movies that tend to most treat their subject in an overly reverent manner. Sure the performer might have flaws (most commonly substance abuse issues), but a heart of gold almost always beats deep within their chest. They never seem entirely human, but more the type of icon their estate would like to perpetuate.

One film that avoided this pitfall was Control, Anton Corbijn’s 2007 biopic about Ian Curtis, starring Sam Riley as the lead singer of Joy Division who committed suicide in 1980. Unlike other musical biopics, this one gave its focus a level of tragic humanity, portraying him more as man than rock legend. Corbijn’s beautiful black and white photography gives the film a true intimacy. As with most intriguing protagonists, his greatest struggle was mostly internal. His infidelity and the pressures of stardom complemented the insecurities that plagued him his entire life rather than simply being shorthand for them.

This “flawed first” approach does what quality films should do – create an interesting character. Goodness rarely has the depths of depravity, and seeing how a person’s negative qualities lead to the creation of works and stories that have transcended time produces a far more fascinating tale than an overall decent man accomplishing something remarkable. It’s the same approach adopted by other genre classics such as Raging Bull and Bronson.

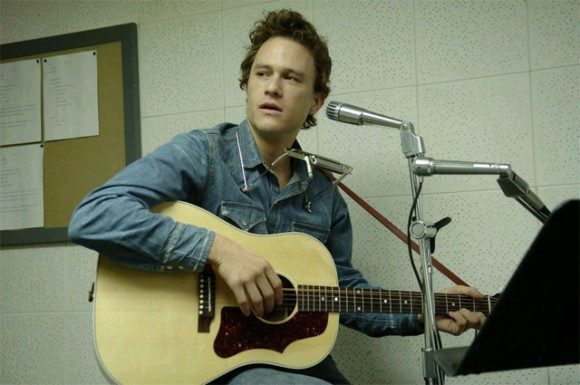

2. I’m Not There, Or When in Doubt, Print the Legend

For some subjects (e.g. Ian Curtis, Charles Bronson), a single film can suffice in capturing their lives and their importance. But for others, an entire mini-series couldn’t do them justice. Few people better represent this than Bob Dylan, and Todd Haynes’ 2007 I’m Not There took a unique look at the many lives of the legend. Along with casting multiple actors (including Cate Blanchett, Christian Bale, and Heath Ledger) to represent the singer at various points throughout his life, Haynes also used different filming styles for each chapter.

This film embraced the power of celebrity mythology rather than boiling away all of a subject’s traits until he ends up as “Generic Smart/Talented Guy.” Biopics are generally about people with larger-than-life (and regularly evolving) public personas that often run in contrast to their mysterious and secretive private lives. Accepting rather than fighting this dichotomy brings us closer to the truth – that we can never fully understand these people – and can create a more fulfilling experience and interesting film.

3. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Or We Are Simply Passing Through History

No person is bigger than the time in which they live, despite the impact they may have had on the culture and the period. Few movies understand this concept better than Andrew Dominik’s 2007 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. Despite being about one of history’s greatest outlaws, the film is more about the death of the Wild West, with James as that period’s symbol than the man himself. With an ethereal look and appreciation of the mysticism of the West (that makes director Andrew Dominik an optimal choice for any future Cormac McCarthy adaptation) and a haunting score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, this film’s dreamlike approach generates a feel of a time that is slowly fading from memory. Sure the name Jesse James lives on, but rarely does a film show a person as part of the landscape as well as this one does.

4. The Aviator, Or With Rare Exception, A Life Is Built Around Relationships, With Two S’s

Many biopics tend to revolve around a love story element, often at the expense of the main subject’s professional and personal interests. Even homosexual Alan Turing is paired with a female companion (Keira Knightley’s Joan Clarke) in The Imitation Game. Similarly, while the romance with June Carter was definitely a crucial part of Johnny Cash’s life, Walk the Line completely ignored the importance that religion had on the Man in Black and his career.

Although a flawed and generally unfocused film, Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator presented several sides to iconic eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes. Naturally, a “love interest” element made its way into the film, as well it should because Hughes was a legendary Lothario. And while the film spent a good deal of time on this aspect of his character, it never really captured just how important this personality trait was to its real life subject. This is a natural problem with the biopic – an inability to capture or fully express all of a person’s inspirations in its running time. (Of course when that running time is a shockingly long 170 minutes, as with The Aviator, the inability to use a “subplot” to land a point only serves to make the viewer feel the time rather than the character/person.)

However, unlike most biopics that place romantic entanglements above all else, Martin Scorsese avoided this trend by understanding that Hughes primarily loved flying and innovation. Despite having multiple women with whom to give Hughes a heart, Scorsese understood that what mattered most to him was taking to the skies, challenging expectations, and changing the world. It would have been easy (and lazy) to portray this drive as secondary to his love of women, but as the title says, he was The Aviator. Despite the numerous love affairs he had in his life (and which the movie barely touched on), by the end of the film, they all but disappear. Unlike other “brilliant” subjects, Hughes’ resilience comes not from love, but from legacy. His desperation/obsession to make the Hercules (aka the Spruce Goose) fly and save his company is what drives him at the end. And this need to prove oneself as superior seems a more believable motivating factor for these iconic figures than the love of a good woman.

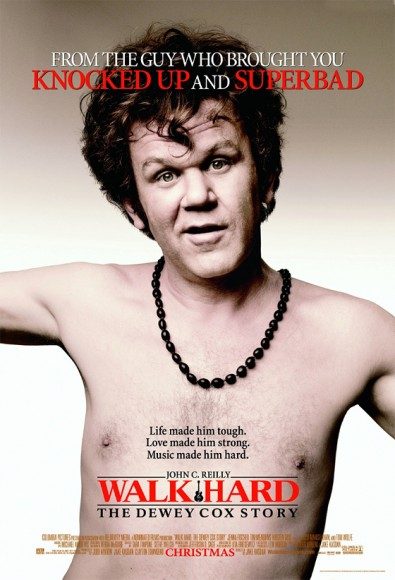

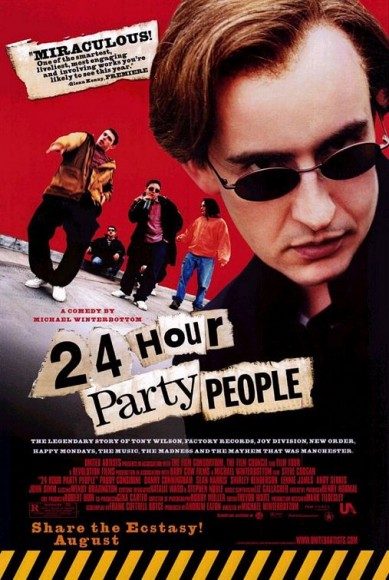

5. 24 Hour Party People, Or Just Go All Out

By now, the audience understands all the tropes and clichés of the biopic – a fact that the terrific 2007 satire Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story capitalized on. Yet not enough films seem to respect the audience enough to trust our awareness. A most notable exception was 2002’s 24 Hour Party People, which successfully took the genre into a delightfully self-aware territory. Director Michael Winterbottom and his regular leading man Steve Coogan told the story of real life reporter (and later head of Factory Records) Tony Wilson and the rise (and fall) of the Manchester music scene of the 1970s and 1980s. With regular breaking of the fourth wall, cameos from real people from the era, and hallucinatory sequences, 24 Hour Party People doesn’t detract from the real story. Instead, it did what good films should do – capture the vibe of the time and the spirit of the main character rather than reiterating the cliff notes or filming the Wikipedia page.

None of the aforementioned examples are the be-all-end-all in creating a good biopic. After all, copying past successes will lead us to the same problem as we’re in now. Regardless of the genre – and whether based on a true story or completely fictionalized – these “imitation games” only cheapen the person by not giving their filmic existence the soul it deserves. Lives might follow similar paths, but a life, especially one noteworthy enough to be made into a movie, should be unique. Instead of honoring filmmakers and actors simply for basing a melodramatic movie on a true story, honor those who express what these people were about. These were original and creative people, and their movies should reflect that.