Aaaaall right… I suppose it’s been long enough since our last editorial about how everything is terrible and we can’t have nice things. Time for another one.

On an interview for the January issue for Australian Women’s Weekly, Russell Crowe, apparently ready to stir up fresh controversy now that anger over his depiction of Noah has been shifted to Christian Bale’s Moses, had some rather interesting things to say about the state of the film industry. Straight from the horse’s mouth:

The best thing about the industry I’m in – movies – is that there are roles for people in all different stages of life. To be honest, I think you’ll find that the woman who is saying that (the roles have dried up) is the woman who at 40, 45, 48, still wants to play the ingénue, and can’t understand why she’s not being cast as the 21 year old.

Meryl Streep will give you 10,000 examples and arguments as to why that’s bullshit, so will Helen Mirren, or whoever it happens to be. If you are willing to live in your own skin, you can work as an actor. If you are trying to pretend that you’re still the young buck when you’re my age, it just doesn’t work.

I have heard of an actress, part of her fee negotiation was getting the number of children she was supposed to have lessened. Can you believe this? This (character) was a woman with four children, and there were reasons why she had to have four children – mainly, she lived in a cold climate and there was nothing to do but fornicate all day – so quit arguing, just play the role!

The point is, you do have to be prepared to accept that there are stages in life. So I can’t be the Gladiator forever.

This little tidbit of insight into the way the Gladiator star sees the filmmaking landscape has exploded into a bona fide internet controversy, incurring public responses from online publications, Meryl Streep, Jessica Chastain, and many others.

Now, let’s get this out of the way: personally, my own take is pretty much in line with Meryl Streep’s very measured and diplomatic response. The ultimate sentiment, buried underneath layers of mistake and ignorance as it might be, is that in an ideal world everyone could and would be acting in engaging, age-appropriate roles. That’s commendable, and there is a degree to which Crowe’s words have been taken out of context in the wider discussions. Reading the quote in full, you do see the way in which Crowe is addressing a larger point, namely the expectations both he and his fans have for the kind of roles he takes on as he ages. Which is not meant to excuse what he said – it really is quite painful – but divorcing it from the conversation going on around it does a lot to tip public perception away from the realms of “unfortunately under-thought faux pas” and towards the lands of “Cro-Magnon hate speech sermon.” Is what Crowe said shortsighted and wrong? Yes. Is it crusade-worthy? Eh, probably not on its own. But is it indicative of long-term problems in the industry? Very much so.

This latest gaffe has been the catalyst for discussion about the gender inequality that pervades Hollywood. There has been a lot of back and forth on why, exactly, these comments are offensive, belittling, and misguided. A lot of conversation has focused on the large number of awards won by older female performers at the Golden Globes, a lot of statistics have been thrown around, and our old friend the Bechdel Test has made a few appearances. But thrilled as I have been to see this particular topic as a subject of widespread dissection, something has been chewing at the back of my mind for the entirety of this new round of discussion. Namely? No one is quite capturing the full extent of what a destructive, insidious problem we’re really talking about.

So if we’re going to talk about this, let’s talk. Let’s address the fact that career prospects in Hollywood for actresses come with an expiration date: 35 years old. Yes, you read that right, 35. Fasten your seatbelts, everyone, this is gonna be a bumpy ride.

First things first: any notion that the only obstacle women over 40 face in acquiring roles is their own immature desire to continue playing youthful maidens is absolute hogwash. Female performers face a very particular set of challenges, ones that have been endemic in the industry pretty much since its inception. This is not up for debate, the statistics are in and they are horrifying. Number of speaking roles played by women? Hovering shamefully near 30%, with only half of those leading roles. Performers’ salaries? Over the past 40 years, male film stars have hit their salary peak around the age of 51 and retained that earning power for the rest of their careers, but female stars see the peak of their salaries at the age of 34, followed immediately by a sharp decrease in their earnings. And let’s not forget the charming fact that Hollywood is all too eager to stick with a leading man over the course of a couple decades, but tends to pair him with actresses in their early thirties or younger for every step of that trajectory.

So just to recap: across the board there aren’t as many roles for women to play as there are for men, and there’s compelling evidence to suggest that the female section of the acting force will get fewer jobs overall and be paid less for the ones they do get the moment they turn 35. Put in other terms, we can get on board with the sentiment expressed when Meryl Streep agrees with Crowe that, “It’s good to live in the place where you are,” but what the veteran actress leaves unsaid is that the reasons why a lot of actresses don’t are not the vain, superficial ones that are implied in Crowe’s statement. The obstacles are coming from the employers, not the employees.

Oh, and speaking of Meryl Streep – I can imagine a few Devil’s Advocates out there pointing to that section of Crowe’s speech. Isn’t she the exception that obliterates the rule? She’s been playing age appropriate roles pretty much her entire career, has been working steadily, and the boatloads of respect and award nominations she gets every year don’t seem to be getting any smaller. She’s thirty years past 35, and she’s not expiring any time soon. All of which is true, but when’s the last time it was a good idea to measure the average anything using Meryl Streep as the standard? She is the exception in every regard, and if our requirement for women being able to work steadily into their 60’s is having nineteen Academy Award nominations, we as a culture are drunk and need to go home.

Since it is the season, let’s talk about the Oscars for a moment. I know that there are plenty of problems that make our most publicized Awards show suspect, but by and by they’re a lot of the same factors that make the Hollywood landscape at large problematic, so they’ll do for a quick illustrative example. Consider the ten men and the ten women who are nominated for acting honors this year. It’s telling the average age of the male nominees, 51, (the exact same age as the average actor’s peak salary, coincidentally) is a full ten years older than the average age of the female nominees, 41.

But look closer – there’s another pattern at work here. Out of all of the actresses nominated this year only one, Patricia Arquette, is over the age of 35 and on her first nomination. (And the cynical among us would joke that Arquette was under 35 for parts of her performance in Boyhood if Amy Poehler and Tina Fey hadn’t beaten us to the punch.) Every other actress is either at or below the dreaded age of 35 or a returning veteran who did get an acting nomination in the early stages of her career. But what do you see in the men’s categories? A much more organic mixture of ages and nominations histories, with multiple first-timers in their fifties or sixties. J.K. Simmons, who is a nominee for the first time at 60, has largely made a career out of playing small characters before stepping into his larger-than-life Whiplash role. Now he’s the bookies favorite for the Best Supporting Actor slot. That’s exactly the kind of luxury that performers with two X chromosomes are not afforded. You need to make your name early in your career while Hollywood is paying attention – you need to be in the club before you hit that expiration date if you’re going to be remembered later on.

Last year’s Best Actress winner, Cate Blanchett, on her sixth nomination. Her first one was for 1998’s ‘Elizabeth’, when the actress was – you guessed it – 35 years old.

Lest you think that this is an aberration, a quirk for this year alone, it’s actually a very prevalent trend if you go further back in the Academy’s history. Sandra Bullock is the only woman over the age of 35 to win a Best Actress trophy without having a previous nomination from a more youthful past life this side of the Millennial divide. You have to go back almost twenty years, to Kathy Bates’s 1990 win for Misery, before you run into another winner who meets both criteria. It might seem like I’m making too much out of this, but the Oscars are a titanic influence on the popular perception of the acting world, and they are a microcosm for the problems at play here. Women like Meryl Streep, Helen Mirren, and Julianne Moore (among others) are consummate artists that deserve nothing less than our respect, support, and admiration, but they cannot be taken as proof that all is well in the world. They are the survivors a broken system wasn’t able to quash, and they get by on the few roles that Hollywood produces for their age bracket every year.

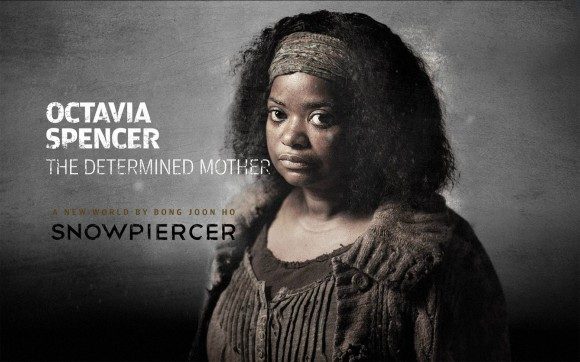

And the fact of the matter is these roles are rare. Want to know how bad things are? Consider one of our favorite films from last year – Snowpierecer. Other articles on this site will attest to how much we love this film and its diverse cast of characters. How badass is Snowpiercer? It creates roles for not one but two Academy Award winning actresses (Octavia Spencer and Tilda Swinton) over the “expiration” age of 35. Which is awesome, but stop and think about the two characters for a moment. What can we really say about Spencer’s character without referencing the fact that she is a mother? Much as we do love the film, and Spencer’s performance, it’s telling that this is such a hard task. Tanya has strength, determination, single-minded focus, but it’s all so squarely aimed at her mission of recovering her lost child that it completely overshadows her individual personality. It’s a good performance, but it’s filling in a stock role, one that is completely defined by the stereotypes that plague older women. Not inconsequentially, a then-28-year-old Alison Pill, playing the Teacher, is one of two other women among the main cast and she fills a similarly stereotypical caretaker role.

But Tilda Swinton’s Minister Mason? There’s a character for you. She’s lying and scheming and petty in that way that only a politician can be. She’s drunk with power and hypocritical, without an ounce of loyalty or integrity to her. She’s cowardly and timorous at times, but also bold and Machiavellian when given half a chance to be. She’s complicated, layered, and bursting with memorable traits. And you know what else is interesting about this character? She was written to be played by a man. Yup. The role was intended for a male performer, but in a moment of inspiration, director Boon Jong-ho cast Swinton to play Mason. Which means that out of the two roles the film had for women over the age of 35, the only one with unique defining characteristics is the one that was conceptually designed for a man. The other one is painfully reflexive of the underlying attitude that a woman of a certain age can be fully understood through her role as a mother. Even in something like Snowpiercer, which is bending over backwards to be a mature representation of the various sectors of humanity, you can only find viable roles for women over the age of 35 by gender flipping roles that are written male. That’s how bad the situation has gotten.

Given all of that, the temptation for an actress to try to prolong that golden period of maximum exposure and peak salary is nothing if not understandable. What adds ironic insult to misogynistic injury, however, is that after breaking that mid-30s barrier, actresses are facing an inverse pressure from the Hollywood Ageist Machine: to play older than they are. More and more stories of actresses being pushed towards roles that are well above their own are beginning to come out of the woodwork. Meryl Streep herself has talked about being offered multiple “witch” roles at the age of 40, a character type that she only felt comfortable playing 25 years later. Zoe Saldana, 36, but who as far we’re concerned looks like the proud owner of a fountain of youth, has accounts of being called “old” by producers. She has an even bleaker outlook on female performers’ chances: “By the time you’re 28 you’re expired, you’re playing mommy roles.”

What could account for Hollywood pressuring actresses to play roles skewing to both the only to the younger and the older extremes? It certainly speaks of a disconnect between the filmmaking Powers-that-Be and the female half of the film-going audience, and the fact that we’re hiring fewer female filmmakers than we were in the nineties can’t be helping. It may well come down to something depressingly simple: the predominantly male screenwriting workforce of America doesn’t know how to write female characters. Or, more exactly, it only knows how to write female characters in a way that marries them to one of the traditional roles associated with the gender. The virgin. The seductress. The mother. The whore. The crone. The witch. All of these can be facets of well-developed characters, jumping off points for something more complex and diverse; on the other hand, if one of these are the character’s chief (or worse, only) defining trait, what is being written is a stereotype, not a person. And as traditionally drawn, these are all roles that lean heavily on either extreme youth or extreme age.

If you are a bit more cynical on society as a whole, you might agree with Emma Thompson when she says:

For women a lot of the time, the only power that they do have in their roles on screen is the sexual power…. So when that sexuality becomes older, and therefore a great deal more threatening, the roles dry up, because women don’t have access to the kinds of power that create the kind of story that people are writing about. The roles of women in life — in political life, business life, everything — are absolutely mirrored by what we see in cinema.

We can leave the wider conspiracy theorizing for another day, but the point about our world being reflected in our art (and vice versa) is one that cannot be overemphasized. We are fortunate enough to live in an era where a lot of the sexist, ageist, misogynistic, and racist structures that have been used to inflict violence upon the female half of the population are beginning to break down in a more meaningful way than ever before. But if we are going to see these changes last, we need to start reflecting them in the art that we make. If we want to sit at the big kids’ table, we need to start telling more stories about women from all walks of life. We need to get more people who can write women in a way that isn’t a reductionist nightmare. Most importantly, we need to get more female artists working in every facet of the industry and defining the stories that are told.

And, for Heaven’s sake, if anyone else feels the need to start talking about the massive problems that women have to brave in order to overcome centuries’ worth of corrosive social conditioning like it’s all their fault, they need to cut it the hell out.