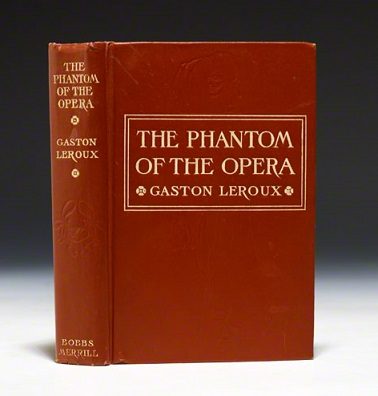

One of the best things about having stories in the pop culture consciousness for so long is seeing how they evolve and are reinterpreted over time. Directors and writers can take characters into new genres, time periods, and universes while ensuring that our artistic past never remains too far from our present. Having recently read Gaston Leroux’s 1909-1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera, I thought it would be interesting to see how different cinematic versions succeeded or failed at presenting the musical maniac, his conflicted crush Christine, and his romantic rival Raoul.

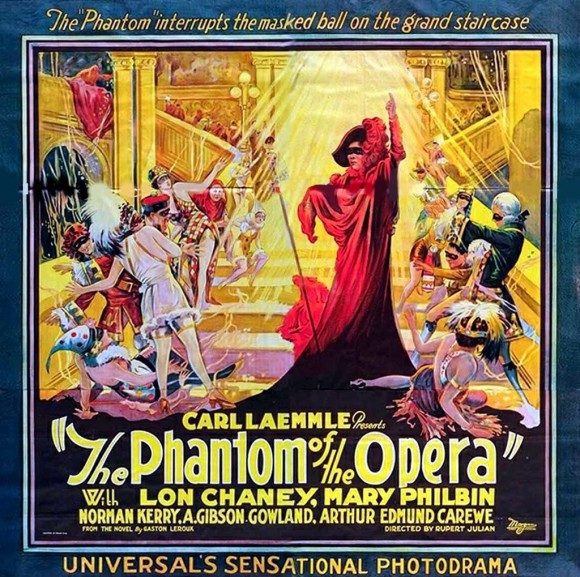

I decided to place Rupert Julian’s silent version from 1925, Arthur Lubin’s version from 1943, and Joel Schumacher’s 2004 big screen version of the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical in head-to-head competition. This contest is divided into four categories: 1) the Phantom himself, 2) the music, 3) the opera house, and 4) the young lovers Raoul/Christine. Which managed each angle best? Which was the best overall? Time to go “past the point of no return” and “listen to the music of the night.”

The Phantom

There’s no Phantom of the Opera without a phantom of the opera (aka the Opera Ghost aka Erich aka the Angel of Music aka the Phantom). In the book, the Phantom is a surprisingly bittersweet figure. A combination of dualities – he is insane and yet romantic, villainous and yet also tragic – whose repulsive “Death’s Head” of a face belies his genius in architecture, music, and torture chambers. In the three films, the titular character was played by Lon Chaney, Claude Rains, and Gerard Butler, respectively, and all three brought something unique to the role. But who did it best?

The clear winner in this category is 1925. Chaney easily stands above everyone else by being the only one who makes the Phantom into something otherworldly. He’s a haunting figure who exists outside of society and genuinely lives in the darkness. His isolation has turned his madness into the stuff of nightmares, and Chaney shows how the Phantom’s thought process operates on a different and far more dangerous level than anyone facing him. Although the film doesn’t make the Phantom as much of a genuinely tragic character as Leroux did (or future versions do), it still treats him with enough sympathy to bring an ambivalent quality to the necessity of his demise.

1943 takes a significant number of liberties from the original story, including with the entire character of the Phantom. The film plays more like a conventional horror flick from the first half of the 20th century and ranks among the Universal Monster Movies alongside Dracula (with Bela Legosi), Frankenstein (with Boris Karloff), The Mummy (again with Karloff), and The Invisible Man (also starring Claude Rains). As with his God’s-law-violating contemporaries, the Angel of Music is presented more in a traditional mad scientist mold (except with music being his raison d’etre instead of mad science) and is even given a supervillian-esque origin story. Instead of being born deformed, he’s an accomplished violinist/amateur composer at the opera house who pays for the singing lessons of Christine. After arthritis forces him to quit playing and he learns that one of his concertos was stolen, he strangles the alleged perpetrator and is scarred by acid before retreating into the bowels of the opera house. Rains is one of the best actors of this period, and his performance is fine for the genre, but the movie disappointingly eliminates a lot of the subtleties of the character.

Admittedly, my viewing of 2004 was my first foray into the Phantom musical in any format so I don’t know how it plays on stage. On screen, Butler did not work for me – though he was far from the film’s only problem. For a character whose main characteristic is his grotesqueness, Leonidas-in-waiting was probably not the best choice as his vessel. (It also didn’t help that his singing left a lot to be desired.) But casting an attractive actor in the role isn’t in and of itself a major issue; the biggest problem was that he doesn’t have the requisite dysfunctional personality. He never seems particularly “insane,” even in that movie definition not approved by DSM-V. He’s more smarmy than menacing, more brute than shadowy lurker of shadows, more possessive than obsessive; the descriptive word that kept coming up in my mind was “douchebag.”

Finally, how does the Phantom look? After all, his grotesque appearance is a dominating element of his character. Once again, 1925 is without peer. While the others look like they have mild scarring or a bad case of eczema, Chaney’s Phantom possesses a truly startling appearance. He bears the Death’s Head visage described in the novel. After nearly 90 years and all the advancements in movie-making technology, only Chaney manages to look genuinely disturbing.

Winner: 1925

The Opera (The Music)

The book is called Phantom of Opera, one of the Phantom’s monikers is the Angel of Music, and he’s in love with an aspiring opera singer. So obviously music should play an important role to any incarnation of the tale. Which film merges music and story the best?

With 1925 being a silent movie, it is obviously out of contention.

The predictable answer should be 2004 since a) it’s a musical and b) has original music. But is that the correct one? Although it only used public domain music to save money, 1943 featured the more interesting relationship with music. It’s the only one of the three where you get a sense of just how important music is to the Phantom. His love of listening, playing, composing, etc. is equal to, if not greater than, his obsession with Christine. It’s one thing to sing and another to understand why you have to sing, and the 1943 knows the difference. Even with the bash-you-over-the-head symbolism, the near-ending shot of the Phantom’s mask lying next to his violin amidst the rubble of the lair showed how intertwined the two were in a way neither of the other two movies accomplished. It also doesn’t hurt that I don’t care for Webber’s score (or, to be more accurate, the orchestrations in 2004) with its heavy synthesizer base, complete with fake claps and “rock” guitar.

Winner: 1943

The Opera (The Place)

As much of a character as any of the people, the Paris Opera House should play a crucial role in any version of The Phantom of the Opera. It’s the primary setting of all the action. The lavish auditorium overseen by a towering chandelier contrasted against the multiple basement levels that make up the Phantom’s domain (and clearly representing heaven and hell) offers a lot of opportunities to set designers and artistic directors. Which film best rose to the challenge?

Many of the reviews of 2004 praised one key aspect of the film – the spectacle. And it succeeded in that aspect, earning an Academy Award nomination for Art Direction. The opera house looks large and painstakingly detailed. The set designers clearly appreciated the opportunity to recreate the decadence (or garishness, depending) of 19th century Paris, and this can be seen not only in the look of the facility but from the myriad of costumes strewn about the set. Unfortunately, the Phantom’s Lair doesn’t work as well as the upper level. When the Phantom sings “down once more to the dungeon of my black despair,” we’re taken to something that looks like a cheap stage set rather than some foreboding hell that epitomizes a demon’s mind. The first time we enter it, we’re greeted with already lit candelabras emerging from the waters. When combined with the synthesizer-heavy score, it looks like one of those artsy 1980s music videos.

Interestingly enough, 1943 and 1925 share the same Paris Opera House set, which is a plus in both the later and the earlier film’s columns. Bolstered by the still visually astounding Technicolor process, it was remarkable to see the level of dedication that silent filmmakers gave to their sets. (1943 also won the Academy Award for Art Direction (color).) My slight favoritism towards this set might be simply because I prefer the blue/grey aesthetic of 1943 to the gold/red color scheme of 2004. Yet once again, the Phantom’s Lair falls short and looks too much like a film set to be truly intimidating.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the bad quality of the film stock, 1925 succeeds where the other two don’t quite measure up: the Phantom’s Lair. This is the only version that really captures the darkness and the murkiness of his home. It’s simultaneously claustrophobic and infinitely large, a labyrinth of sadistic death traps. Escape is utterly futile unless the Phantom wills it, because it is as much a part of him as the mask and the music.

Winner: 1925 – if only because 1943 showed off the opera house to complement the Lair.

Christine/Raoul

The problem with the characters of, and the relationship between, Christine and Raoul is that they are such dull people; Raoul especially. At least Christine has the excuse of being a 19th century ingénue put up on a pedestal by two ridiculously controlling guys. Raoul’s primary trait is that he had a childhood crush on Christine that he never got over, which makes him very much like the Phantom with their shared, creepy adoration for this barely legal chanteuse. Even in the book he is an incredibly weak character, with The Persian (a former associate of the Phantom who hangs around the opera house) handling most of the heavy action during the climax. But which pair prevailed?

The faithfulness of 1925 to the source material was both a benefit and a burden. This one, featuring Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry as the aspiring lovers, brought with it the problems inherent with the duo. However, I bought into their chemistry and their relationship the most of the three pairings. Yes, they were little more than starry-eyed lovers, but that played to their simplicity. As with the book, Raoul can take no credit in defeating the Phantom, who decides to let them go after Christine begs for their lives and before being chased and killed by an angry mob.

1943’s Susanna Foster and Edgar Barrier were the most modern of the three couples, but they still didn’t possess particularly strong personalities. Of course, this is par for the course, especially in horror movies where the “good guys” are really just straight men while the monster steals the show. Here, Raoul is the most effective at stopping the Phantom, and that’s only by aimlessly shooting a gun and unexpectedly causing the Lair to avalanche- which really showcases just how inadequate Raoul actually is.

Nevertheless, this version had the cleverest resolution to the relationship subplot. Concluding on a semi-comic note, the film has Christine becoming a genuine opera star and greeting her fans instead of joining Raoul for a celebratory meal. Raoul responds by graciously accepting a dinner invitation from the original-to-this-movie character Anatole Garrona, a quasi-rival/foil from earlier in the film. A woman choosing a career over a husband and the man being okay with it? Quite forward thinking for the 1940s.

Or did they fare the best as Emmy Rossum and Patrick Wilson in 2004. They sang, so at least that gave them some personality and afforded us insights into their minds. Rossum’s Christine was the best leading lady of the three, with the Shameless star imbuing Christine with the proper level of youthful innocence and emotional distress. Wilson’s Raoul was more active than most incarnations by having sword fights with the Phantom…that our hero promptly loses. Yet he also seemed the most foppish and out of his depth in dealing with the insanity. Additionally, their relationship was the most chaste and loveless of the three versions. For a third time, Raoul is almost completely ineffectual in stopping the Phantom, as the Opera Ghost decides to let Christine choose her own path after she shows affection towards him. Despite the problems, the introspective moments through verse and a superior Christine pushes this one to the top of the list.

Winner: 2004 – though 1943 gets some credit for its ending.

Final Verdict

This is a difficult question to answer as there is really no “stand out” version. 1925 is easily the most faithful to the source material and the most interesting, but I can understand the hesitancy to watch a silent film- especially one without a decent restoration available. 1943 is more of a traditional early monster movie with the Phantom of the Opera name than a true adaptation of the source work; it has good visuals and decent performances for the type of movie it is, but it’s far from being a great film. 2004 has a decent visual sense, but it’s overlong and you can’t give too much positive credit to a musical with bad music.

Overall Winner: 1925