Kurt Vonnegut’s bestselling novel Slaughterhouse Five (1969) is a forever iconic satire of war and an ample critique of free will. Adapted for the silver screen in 1972, Slaughterhouse Five the movie never became as popular as the book. However, it’s important to note that the film does present itself as an interesting cinematic representation of the novel, aiming to create a visually and auditorily phenomenal experience in order to express the temporal absurdity that is evoked on the pages as well as making an aesthetic comment on Vonnegut’s overarching thematic critique of free will.

The story that unfolds, folds, and unfolds again in Slaughterhouse Five is one that questions the role of predetermination and our relationship to fate. The narrative places emphasis on the idea that everything that occurs is meant to occur in the predetermined timeline that we happen to coexist within. Our protagonist Billy Pilgrim (Michael Sacks), like most of us, takes time for granted. Time is not necessarily a concept that we grapple with on an active or constant basis although our entire lives essentially revolve entirely around it. However, when we think about how we interact with time and our relationship to it, we seem to value our temporal existence and make decisions to give it meaning and to give us purpose.

The film’s presentation of Billy’s character doesn’t portray him as anything that special despite the fact that he is the only vehicle that can travel back and forth in time, which he has no control over. He doesn’t take much initiative in the decisions he makes in his life. He’s drafted into the war rather than volunteered, attempts to surrender to the enemy rather than fight back, and passively accepts whatever life throws at him. This trend in Billy’s story is only challenged once. On their way to an optometry convention in Montréal, Billy and his father-in-law Lionel Merble (Sorell Brooke) are on a charter plane with a barbershop quartet and others when Billy travels forward in time to see that the plane crashes and he is the one survivor. He runs to the cockpit before take-off to warn the pilots about the crash, but they don’t take him seriously and brush him off as just another drunk passenger. Sure enough, the plane crashes, and everyone dies but Billy. Although Billy tries to take initiative in an attempt at preventing such an awful event from happening, the crash happens as it was supposed to and the consequential events follow suit.

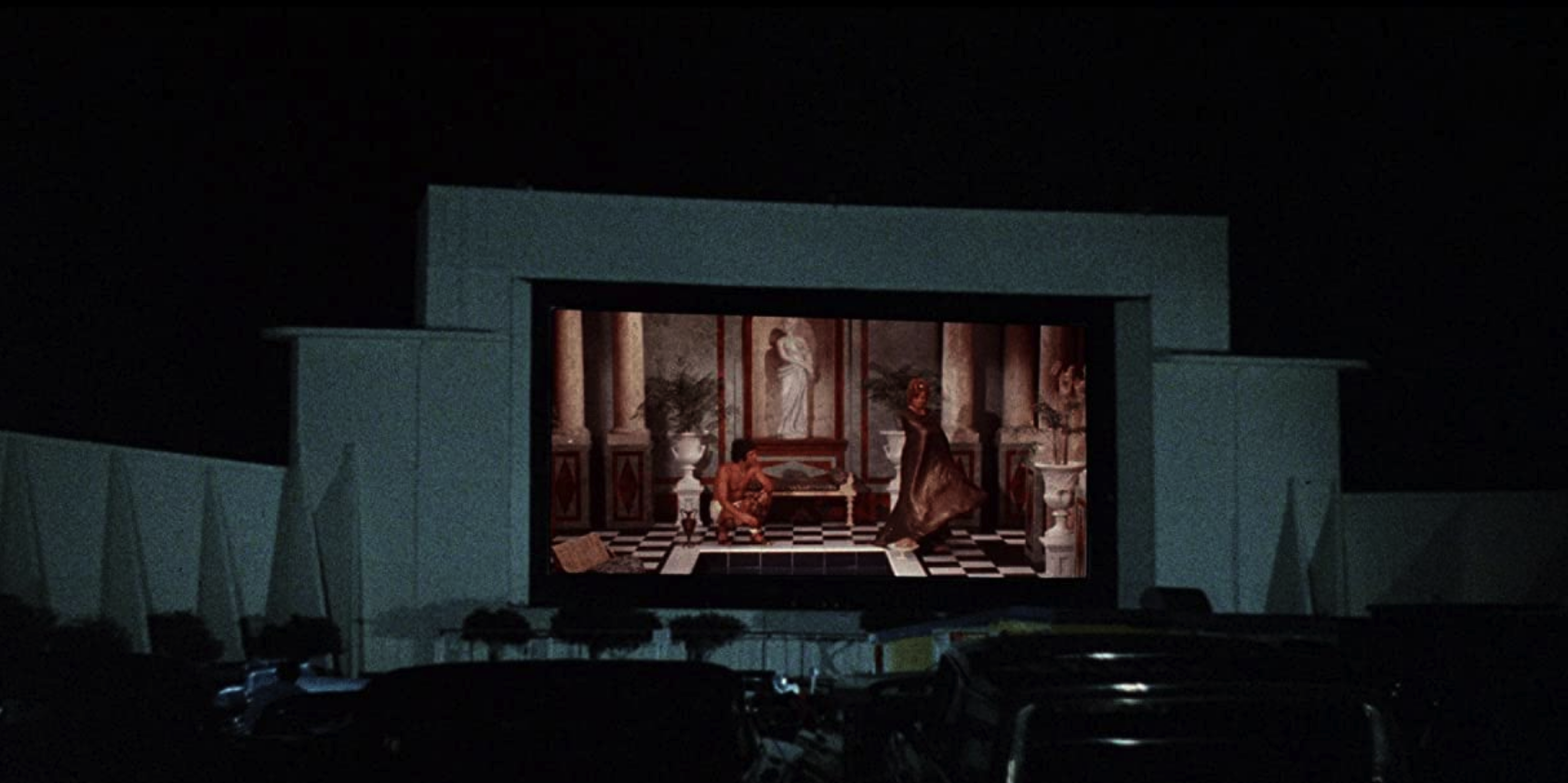

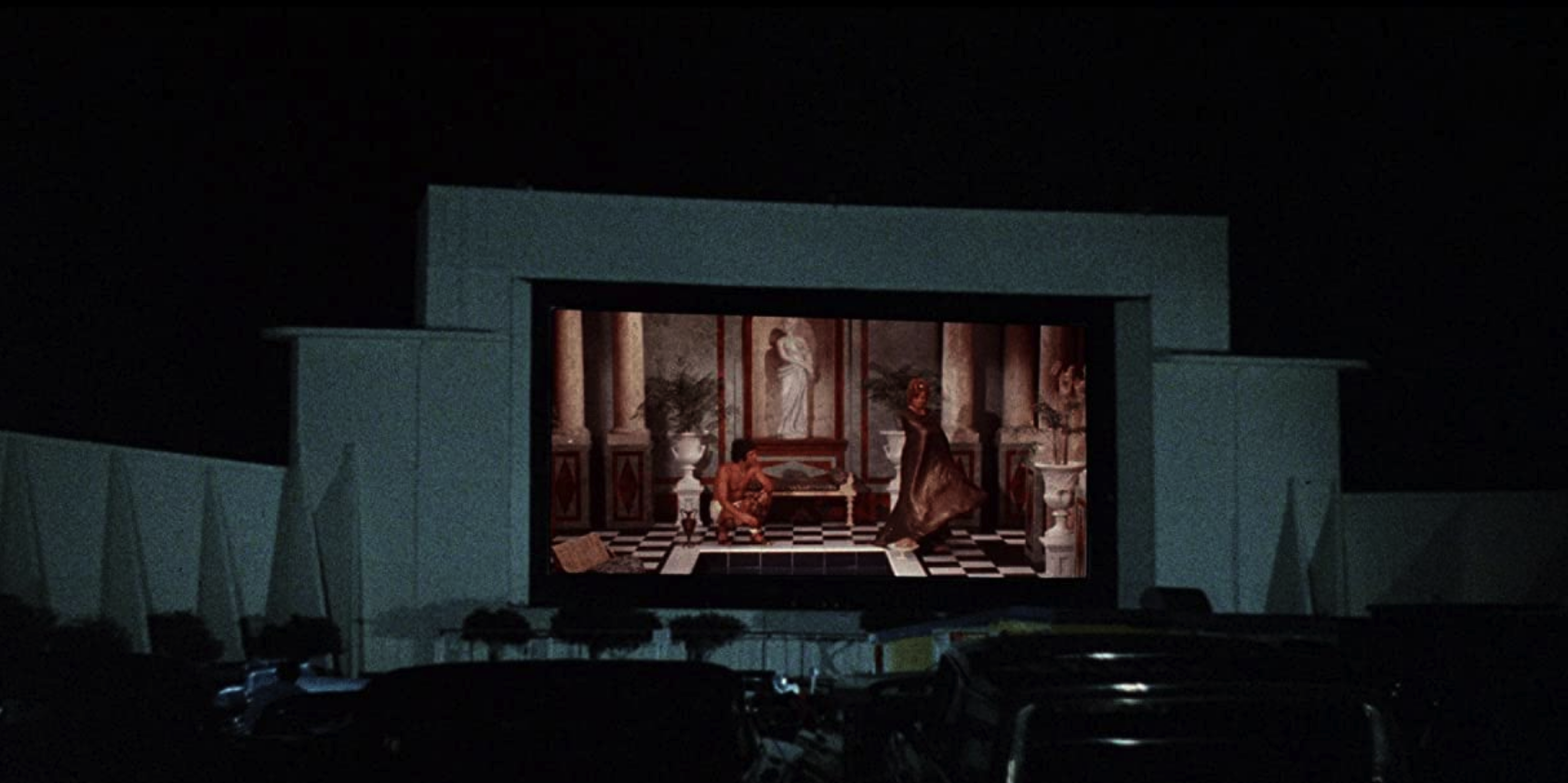

Aesthetically, Slaughterhouse Five brings the viewer and Billy together through the senses with strategic framing by cinematographer Miroslav Ondríck and editing by Dede Allen. With a seamless fluidity, Allen brings together the paralleled shots of the narrative’s past, present, and future by relating sounds and images together and timing their discontinuous continuity in a way that jars the viewer while maintaining their loyal narrative identification with Billy.

By rejecting the traditional methods of continuity, the film is able to emulate the time travel experience that is described in the novel. Billy recalls certain sounds, images, and experiences that will trigger memories of time’s past and future. In the opening scene of the film, Billy is at his typewriter writing to the Ilium Daily News Editor about how he has become “unstuck in time.” The sound of the keys clicking on the page blend with the sound of an army tank engine which alerts Billy in a close up of his face jolting up. The following shot brings Billy and the viewer back to World War II in a snowy European Forrest with a German troop march along with one of their noisy tanks. The pace of this sequence is so quick that it jars the viewer at first (especially if they’re not familiar with the story). As sequences like this compose the narrative structure of the story, the film itself mimics the philosophy of predetermination and the lack of free will in the very active engagement with it.

As an alien influence within the story, the Tralfamadorians are able to critique the idea of free will on Earth that they observe. They describe it as a uniquely Earthling idea and discuss it as an absurd interpretation of our experience of time. The emphasis of this criticism of free will is identified in Billy’s experience of the world and that of the viewer. With Billy, we become dragged along these events of pure predetermination and circumstance, essentially giving up our own control to the narrative trajectory that occurs on our screen, solidifying the story’s argument against free will. This idea of predetermination within the engagement of watching movies isn’t limited to just Slaughterhouse Five. As a medium of art that demands our sensual attention and guides it, film essentially controls our temporal experience at our own surrender. But this leaves us to question the interrelationship and interaction between the film and the viewer as something that isn’t passive but rather engaging as we indulge in the experience of watching movies.