Ahh, l’amour. The swelling strings, the longing looks, the big celluloid-melting kiss at the end… by now these feel like permanent fixtures on the silver screen.

Romance has been a major staple in the world of filmmaking since the birth of the medium, and as the years have gone by romantic films have been omnipresent and consistently popular. And of course, over the years we’ve seen so many romantic films that the inevitable has occurred: we’ve gotten to know them too well. The rhythms have become familiar, the plots predictable, and the payoffs trite. There’s no film genre as constant, which means that there’s no genre as predictable and formulaic, right?

Wrong, actually. Romance films have oftentimes been bound by conventions and clichés, it’s true, but over the years they have also been some of the most fertile ground for filmmakers looking to shake things up and break the ground with some narrative or formal innovation. Maybe it’s the fact that we’re all so familiar with the storytelling methods and tropes in this arena that gives filmmakers the necessary confidence to step out of the comfort zone and try something new.

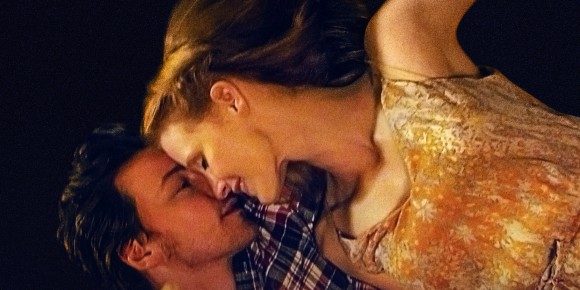

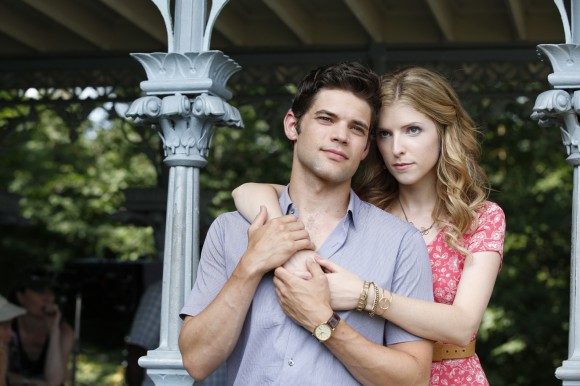

Case in point: two of the most talked-about upcoming romantic films appear to be film-long formal experiments. Director Ned Benson’s The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby, just now going into limited release, is three films that all show the development of the same romantic relationship: one from the male participant’s (James McAvoy) point of view, one from the female participant’s (Jessica Chastain), and one that shows them side by side. The film comes off as much as an exercise in comparing and contrasting perspectives as it does as a love story. Meanwhile, Last Five Years, a new romantic musical starring Anna Kendrick and Jeremy Jordan, has been turning heads since its premiere at the Toronto Film Festival. On top of the singing and dancing, the film is also a chronology-eschewing narrative, cutting back and forth between Jordan’s perspective, which shows the advance of a romantic relationship from start to finish, and Kendrick’s, which starts with the disintegration of the leads’ marriage and goes backwards all the way to their first meeting.

This is hardly a recent development, though. For as long as there have been romantic films, there have been directors pushing the envelope of what could be done with the genre. So if you need something to tide you over until Eleanor Rigby or Last Five Years opens in a theater near you, consider checking out some of these past mold-breakers.

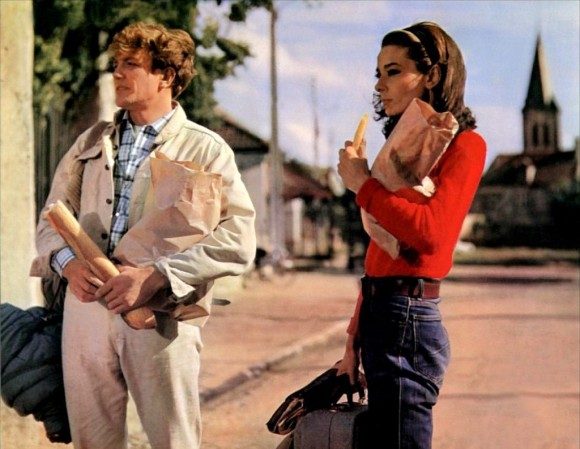

From the 1960’s: Two for the Road by Stanley Donen

An unusual British hybrid from the roaring sixties, Two for the Road is a non-linear romantic comedy travel film. (How many of those have you seen?) The film opens with Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney, unhappily married for a few years, taking a trip to France. As they travel they remember and discuss their first meeting and various major landmarks in their relationship. The film cuts back and forth between these memories and the present, not in any kind of chronological order but free-association, (500) Days of Summer-style, with a line or an image from one memory leading into another one from years later, and different time periods blurring or bleeding together. The film uses this unusual narrative conceit to explore the relationship between the two leads and to build up to their ultimate decision of whether to stay together or go their separate ways.

Two for the Road is a film that brings together the best of two divergent worlds. It’s very much made in the anarchic, can-do spirit of the 1960’s, but it’s clearly made by folks who were brought up in the classical storytelling world of old school Hollywood. The result is a film with a dazzlingly complicated central conceit, but lots of clever tricks and signposts to guide the audience. All of the memories are of various trips the couple has taken, and certain recurring locales, events, and exchanges help to keep us grounded to the point where even with all the jumping around we never feel lost or unsure of where we are in the relationship. And, best of all, it’s still a terrifically funny movie, the complicated narrative gimmick working in the service of the film’s unique humor and the viewer’s cinematic experience, not the other way around.

From the 1970’s: Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky

No, not the George Clooney thing, the other one. With the subtitles. Solaris is an underseen gem that many will miss out on because of its unusual combination of elements. It uses a hard science fiction premise to launch its story, but, once it arrives at its central conceit, what develops is something that is much closer to a romantic film’s sensibilities than a 2001-esque space adventure. A cosmonaut is sent to a distant space station to investigate a series of mysterious goings-on. Upon arriving there, he discovers that the crew have made contact with an alien intelligence, one that is capable of looking into their memories and recreating elements from their past.

In our protagonist’s case, the fixture of his past that the alien decides to present to him is his wife, who committed suicide a few years prior. From then onwards, the film focuses almost completely on their relationship, and on the cosmonaut’s questioning of how much the woman standing in front of him is his wife. If she looks like her, feels like her, and even has her memories, is she really the same person? And if this means that he can be with a loved one who he thought was lost forever, how much do those answers matter? Solaris uses its science fiction elements as a springboard to arrive at those questions about identity, relationships, and love, borrowing from another genre to tell a different, more unusual slant on a romance film.

From the 1980’s: Betrayal by David Jones

Betrayal is based on an acclaimed play by Harold Pinter, who in turn based the play on his own experiences with an extramarital affair. The film follows the affair between Jerry (Jeremy Irons) and Emma (Patricia Hodge), and their evolving relationships with Emma’s husband Robert (Ben Kingsley). The trick to the film is that it’s a proto-Memento, with each scene taking place before the one that preceded it. The film’s first scene, set after the affair is over, is the last one chronologically, while the last scene, the start of the tryst, is the earliest.

What’s remarkable about Betrayal, aside from the sheer novelty of its structure (which admittedly feels a bit less shiny now than it did when the film first came out) is how much the film feels like a commentary on romantic films. The time-reversing trick lets the film tell a tragic story within what feels like the structure of a regular rom-com. The central couple starts out fighting and not able to stand one another, and the last scene ends with an admission of love between two people who have been slowly gravitating apart from each other for a long time. It feels both familiar and unsettling at the same time, and it’s one of the most effective and emotionally draining portraits of a doomed relationship ever put on film.

From the 1990’s: Run Lola Run by Tom Tykwer

All right, all right, I can already see some of your eyebrows rising, but just hear me out. Yes, Run Lola Run is nominally a thriller, a fast-paced race against time film that might even be considered an action movie. The key word there is “nominally,” and, much like Solaris, I think the film uses all of that to get to a different point.

The film centers on Lola (Franka Potente), a young woman whose daily routine is interrupted by a call from her boyfriend, Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu). It seems that he’s run into some problems with local criminals who are going to kill him if he doesn’t cough up 100,000 marks (it takes place in Berlin) in twenty minutes. Lola begs him to hold off on his desperate plan to rob a supermarket, and promises she can get him the money within that time frame.

The rest of the film is a collection of different ways in which the next twenty minutes play out. Lola and Manni try out one plan, we see what happens, and then the film resets back to the opening scene and we see a different version what they might have done play out. Some of their plans fail miserably, others come close to working, and some… well, you’ll have to watch the movie. It’s a version of the video game-like trial and error plot structure, the kind that we saw in this year’s Edge of Tomorrow. What’s interesting in Run Lola Run is what doesn’t change with each reset. Lola and Manni are constant fixtures, with each successive run showing us different facets of their relationship. It’s an unusual way to reveal detail and character, but once all of the adrenaline-soaked iterations of Lola’s run are done, what has been developed is our understanding of that couple, and what we’ve become invested in is their well-being as a unit. It’s an aggressively different form of screenwriting that works through the mechanics of an action film, but the ultimate payoff is straight out of a romance picture.

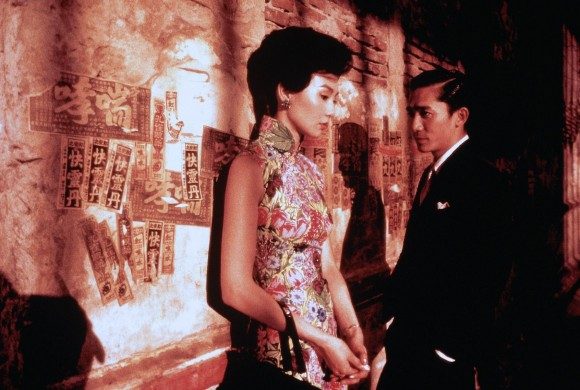

From the 2000’s: In the Mood for Love by Wong Kar-Wai

No, I’m not putting Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind here, simply by dint of the fact that you’ve all seen it, you all know how great it is, and I don’t need to tell you how awesome of an experimental romance film it is. Instead, let’s turn our attention to Hong Kong, and to Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love. The film centers on two next-door neighbors, played by Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, in 1960’s Hong Kong. Both are married to extremely busy, never seen spouses, and both find themselves struggling with loneliness. They become friends, and soon discover that their respective spouses are having an affair with each other. As a way of coming to grips with how something like this could have happened, they decide to act out various imagined scenes from their spouses’ affair. Slowly but surely, however, their playacting involves less and less fiction and starts to blossom into an affair in and of itself.

… or does it? This is the main question at the heart of In the Mood for Love, and the essence of what makes it such an insidiously tricky film. It’s an incredibly minimalistic film, one that gives you the barest information to go on. The further the film goes, the harder it is to tell when the two characters are acting, but not in the way you’d expect. You sometimes have a sneaking suspicion that you want them to not be acting when they actually are, or you’ll be caught off guard by the sudden realization that a very emotional scene you just saw was all part of a roleplaying exercise. It’s a film that holds your attention by keeping you guessing, and which sometimes makes you feels more romantic and more emotional by the fact that it’s withholding so much of that from the characters that are on the screen.

Will The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby or Last Five Years be one of the romantic formal exercises that we’ll remember from this decade? It’s hard to tell until we’ve seen the films, although both show signs of promise and of danger. Eleanor Rigby has one of the most ambitious conceits that we’ve seen in years, and it’s the kind of thing that might well be studied in years to come as a pioneer that expanded our concepts of how films can work … if it works. If it doesn’t, it’ll be asking an audience to sit through six hours of film largely to repeat lines and events various times. Chastain and McAvoy already show simmering chemistry just from the trailers, but the production’s emotional payout better back a wallop.

Last Five Years plays it a bit closer to known territory, relying on a popular and very acclaimed stage show for its base materials. But the play version of the property is a famously stripped down affair, boasting only its two main actors on a practically empty stage. This allows the audience to focus on its development of plot through song and on the two evolving tracks that make up the show’s plot. The film will inevitably have more bells and whistles, an opened-up world that features many more avenues of distraction and engagement. Will it prove a bit too much to bite off? Let’s hope they have someone on had who’s as good at focusing the audience’s focus and attention as Stanley Donen was.

How will these two films fare? We’ll find out, soon enough.