Waste comes in many different forms. We interact with waste incessantly as it has become an inherent part of our daily lives, a part that is, in full irony, non-disposable. We can most commonly associate the idea of waste with that of trash or rather things that no longer serve their purpose to us. Waste can also manifest itself as our perception of time. In hindsight, time can be felt as though it was wasted, and before you know it, that time manifests physically in our appearance as we age. In her documentary Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse (2000), Agnés Varda embarks on a self-reflexive journey that looks back in time to the practice of gleaning, picking up after the harvest, and creates an anthropological portrait of gleaners past and present, and reestablishing our understanding of waste.

Opening the documentary with the Larousse definition of “gleaning,” we are introduced to the subject with a painting by Jean François Millet, The Gleaners, 1857. A depiction of three women picking up wheat after the harvest, this painting was part of a revolutionary wave in art history that focused on highlighting scenes of peasant life during a time when the arts were still considered of high and aristocratic value and were expected to cater to the likes of the wealthy elite. The Gleaners exposed the upper echelon to the lives of those they choose to ignore and take for granted. Bringing the lives of the gleaners into view, Millet creates discourse around this idea of waste. The gleaners themselves, living on the margins of society, are taken for granted as a waste of society, yet they’re shown here taking action, picking up the waste from the harvest to survive. Like Millet with his painting, Varda takes her camera to expose the lives of those who still glean in our contemporary post-modern society from the country fields to the city streets.

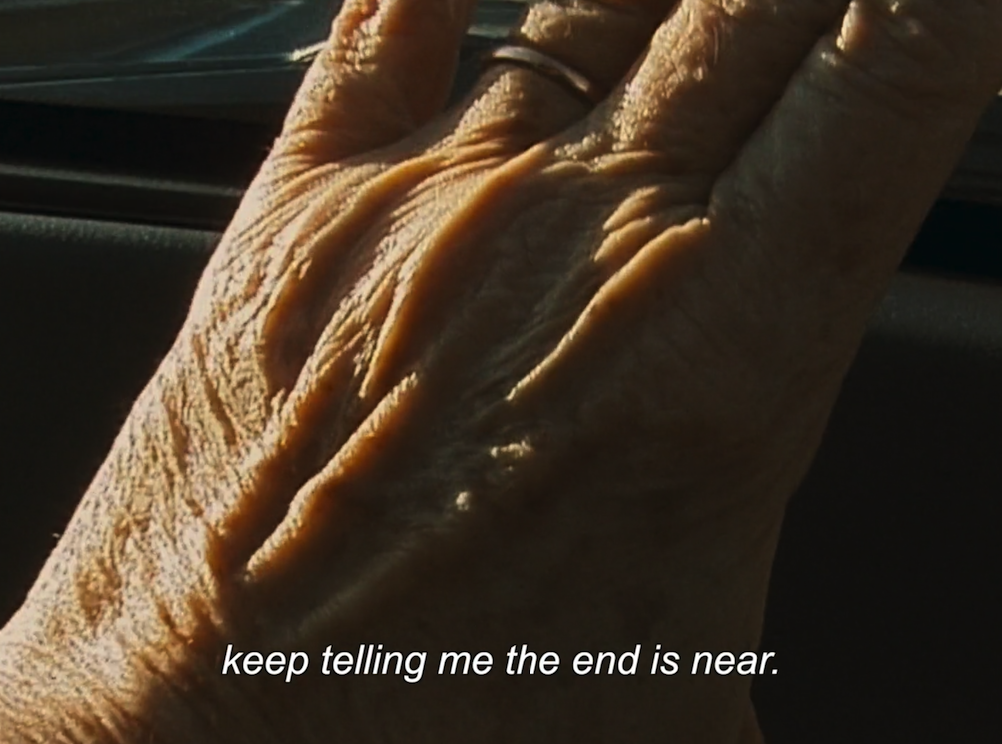

The Gleaners and I was Varda’s first film made on a digital camera. She uses this film as an opportunity not only to spotlight the culture of gleaning, its legacy, and its people but also to reflect on the passage of time and how we can capture it. Prior to diving into her subjects, Varda begins the film by discussing the concept of digital media as she reflects on how she represents herself through the camera, creating a semi self-portrait that plants the seeds for the discourse around representation and digital filmmaking. She describes digital media in three words: stroboscopic, narcissistic, and hyperrealistic. As stroboscopic, she shows the viewer close-up images of her face glitching, visually showcasing the pixels themselves in stroboscopic distortion, exposing its nature and even its flaws. As narcissistic, she gives us a shot of her holding a mirror in front of her face towards us, the viewer. The instantaneous nature of digital media leaves us more immediately concerned with the results which can possibly even suggest an urgency to document ourselves not only out of pure curiosity of how we self-represent but also out of fear of necessity to capture our existence before it’s too late. Finally, as hyperrealistic, Varda turns upon her own body, in tune with this idea of necessity, as she combs through her dyed hair, exposing her white roots, and giving us close-ups of her hand, reminding us over a voice-over that her “hair and hands keep telling [her] the end is near.”

Varda introduces the viewer to gleaners of all kinds across France. At a potato farm, Varda examines how they conduct their harvest and the process of evaluation before they hand off their potatoes to the local grocery stores. We learn that because the grocery stores only accept potatoes of certain criteria, around 25 tons of those harvested potatoes are rejected for being too big, deformed, or discolored. As Varda’s voice narrates the potato-rejects’ journey back to the field, shots of this journey visually capture the gravity of this waste. Jump cuts from different angles become increasingly shocking as the mounds of potatoes get bigger and bigger. Due to the incredible waste that is left behind, the farm operators claim to allow the local community to take free reign to collect from the rejected potatoes that are left behind, bringing about the resurgence of a gleaning community. However, there is no evidence that they themselves encourage others to come. Rather the community must fend for themselves, having to observe the farm’s practices to know when it is time for them to glean.

Varda brings us into the living environments of some of the gleaners in the local community. Living in rural poverty, for many of these people, the waste they encounter is their primary means of nutrition and income. A shot of an abandoned mangled car serves to visually parallel the shots of potato waste as another example of what waste can be. We learn that members of the community take cars apart to sell the scraps, but with no tools or electricity, the car remains an idle inconvenience, much like how we interpret waste itself. Like the potatoes and the car scraps, these people are overlooked by mainstream society, as many of them were cast out and abandoned, left to make use of the waste they found themselves in to survive.

By the end of The Gleaners and I, it’s almost impossible to not feel angry towards the overarching powers-that-be that allow and even encourage the incredible waste problem our planet faces that only seems to get worse. However, what Varda does in addition to bringing gleaning to light, is spark conversation over how we can interact with waste of all kinds, including this greater reflection on our lives and time spent, leaving us motivated to apply more intention to everything we have in both our material and immaterial lives.