Charm is not required for a film to be successful, but it helps, particularly if the film sits within the growing amorphous “dramedy” genre. It is possible for films to succeed when purposefully devoid of charm; last year’s Nightcrawler comes to mind. What isn’t possible is for a film to succeed on charm and charm alone. Actor turned writer / director Frank Whaley’s Like Sunday, Like Rain seemingly defines this warning.

Frank Whaley’s script doesn’t feature much in the way of plot. Issues occasionally crop up, but they often seem to resolve themselves. Eleanor is given the job looking after Reggie, still a child, after a cursory interview with no background check. The film’s, “We don’t usually do this,” explanation is unconvincing and, more infuriatingly, keeps stakes painfully low. Most of Reggie’s inconveniences are solved by “financial arrangements” he has, although the film never investigates the absurdity behind a stream of grown men receiving pay offs from a preteen. He just sends them a check, and they’re apparently okay with that.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing about this lack of conflict is that the film is rife with narrative potential. Eleanor’s relationship with Dennis is woefully unexplored, leaving Armstrong little to do but complain about the guitar Eleanor threw out his apartment window when she decided to leave him. Eleanor’s septic family life and its parallels with the immense void between Reggie and his mother are also left fallow. Conflicts here are treated with as little thought as the characters themselves, as something to be displayed or explained but not investigated or conquered.

With little else to distract from it, the film centers firmly on Eleanor and Reggie’s relationship. This isn’t an inherent problem, but the utter lack of tension between them is. The two get along famously, despite Reggie being an infuriatingly precocious pedant. Eleanor first meets Reggie outside his classroom without his mother, and he immediately trusts her because despite his massive intellect he never considers the fact that someone might abduct him. Maybe he’s just confident that his driver, who used to work for John Gotti, will kill anyone who attempts something like that. This would be the same driver that Reggie pays off to let him walk home. Reggie’s world is filled with these bizarre idiosyncrasies, and the fact that the film refuses to cash in on them make their inclusion feel embarrassingly incidental.

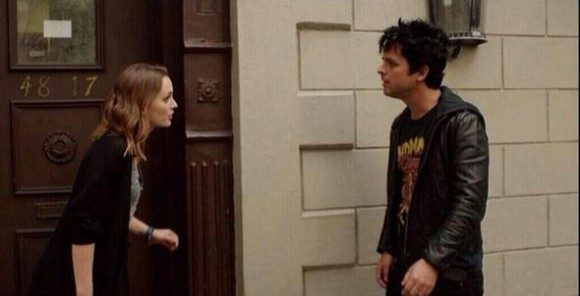

Performances are solid all around, but with so little to do, it’s difficult to feel engaged. Leighton Meester squeezes every ounce of empathy out of Eleanor and proves herself more than capable of shouldering a film with more dramatic weight. Armstrong makes the most of his brief appearances. The phrase, “This film needs more Billy Joe Armstrong,” is not one I thought I’d be saying any time soon, and I hope he pursues meatier film work. Messing fills out the role of overmedicated rich wife fine, although with less than five minutes of screen time and a character with the depth of a fortune cookie, the role feels more like a cameo than an actual part. There’s certainly talent in the frame, but with a script that’s content to have them flop on top of each other like a pile of wet blankets, there’s not much they can do.

The Verdict: 2 out of 5

Solid performances from Leighton Meester, the young Julian Shatkin, and the surprising Billie Joe Armstrong save this from being a complete disaster, but Whaley’s anemic script does the best to suck the life from them. Like Sunday, Like Rain was never going to be a tense, loud movie, but even quiet films can have gripping drama at their core. Watching Like Sunday, Like Rain, it’s difficult to parse out what the film is driving at. It’s a music film with little to no music in it. It’s a drama with no real drama. Really, the only thing to hold on to is the somewhat cute relationship between a woman and a young boy. Unfortunately, that’s just not enough.