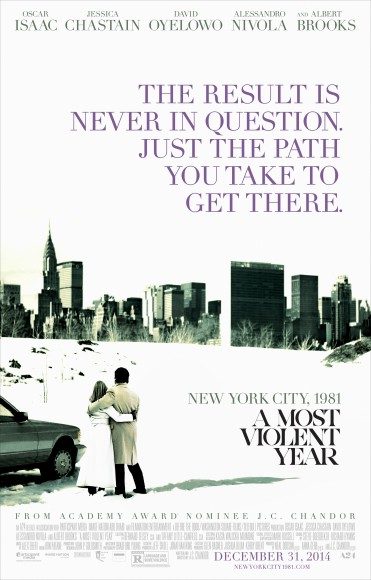

J.C. Chandor may not be a name you’re familiar with, but if you haven’t heard of him before, rest assured that he’s a director right on the fringes of the public consciousness. If you’re a movie buff, you’ve probably at least heard of Margin Call, All Is Lost, or both. The former garnered an Oscar nomination, while the latter featured Robert Redford’s biggest and best role in years. All this to say that there’s a quiet energy that surrounds a Chandor release, and with Oscar Isaac and Jessica Chastain in the leading roles, A Most Violent Year has no excuses for not punching its weight.

That’s where things get a little tricky, because purely on a technical level, A Most Violent Year is great. The tense literal isolation of All is Lost is replaced by tense functional isolation as Abel Morales (Isaac) must fend off threats to his business on multiple fronts and it seems he can rely on no one but himself. Abel owns a major heating oil company, but a new capital investment is being threatened by an inability to secure a loan that should have been a sure thing, he’s under felony investigation by a local DA (played by David Oyelowo), and his trucks are being routinely hijacked in the midst of New York City’s most crime-ridden year on record.

And all that basically works. We understand the pressures that Abel is feeling. The film is beautifully shot in muted tones by cinematographer Bradford Young (Ain’t Them Bodies Saints). The chill of the New York winter is palpable in the costume and production design. A score by Alex Ebert (All Is Lost) that walks the line between orchestration and tone music feels perfect for the early ‘80s setting. Oscar Isaac proves that Inside Llewyn Davis was no fluke based on his musical talents and he’s more than capable of anchoring a major film. There’s nothing really wrong with any of it except for the fact that it doesn’t add up to much.

It’s very difficult to say why Abel’s story is one worth telling outside of a minor shot about the inherent absurdity of the American Dream, something his wife Anna (Chastain) ruefully throws at his feet in a scene where they have a fight over Abel’s business methods. Abel bought his business from Anna’s notoriously crooked father, and while there are some of Abel’s methods that may stretch just past legal, to his credit he is a hard businessman but not a gangster, and he’s intent on keeping it that way. In fact, Anna proves the most interesting character in the whole film because she doesn’t share Abel’s qualms about trafficking in morally gray areas; in fact, she feels underutilized here, both because of the complexity of the character and the talent with which Chastain portrays her. But to get back to the point, this is about as close to a unifying theme A Most Violent Year gets – the question of what lengths you will go to in order to see your dream realized.

But this isn’t, say, Scarface, or perhaps even more appropriately, The Wolf of Wall Street, so A Most Violent Year is paradoxically short on scenes of actual violence or other forms of calculated debauchery. Instead, it poses the flipside of the same question, one of motivation.

About halfway through the movie, Abel’s lawyer Andrew Walsh (Albert Brooks) asks him why he’s doing all this, why his business is so important to him, what his drive is, and Abel functionally has no answer. He kind of says, “I do this because that’s what there is to do.” There are little pieces of rational justification – of a competitive spirit, of wanting to provide a good living for his family – but these aren’t answers to the question of why Abel tries so hard and risks so much. He just does. And I suppose you could say that’s what the movie’s about, the emptiness of human endeavor, almost a character study in existentialism, but I don’t think the narrative ever does enough meaningfully address that idea. In fact, there’s a moment at the very end of the film where I thought the movie was going to suddenly take a very bold turn and actually declare itself for that very theme. And then…well, it didn’t, and I was left again feeling the whole project was a little empty. Read some meta-commentary in there if you want to, but I think that would be stretching.

The Verdict – 3 out of 5

You can’t say A Most Violent Year is a bad film. There’s too much it gets too right, especially in the details of the technical execution. You can’t even say it’s uninteresting, although pacing can be an issue given the struggles to latch onto meaning in the plot. But it is that very feeling of significance that has driven writer/director J.C. Chandor’s work in the past, and it’s lacking here. Oscar Isaac still manages to carry a flawed film, but A Most Violent Year never figures out how to take advantage of its most interesting complexities.