“There are no two words in the English language more harmful than ‘good job.'” That’s the philosophy of Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons), the hard-as-nails star instructor at a prestigious Manhattan musical conservatory. Whiplash, the absorbing and invigorating new film from sophomore filmmaker Damien Chazelle (Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench), adheres to that statement as well. With Chazelle’s sharpened refusal to sugar-coat the process of creating art or becoming a great artist, Whiplash offers an intense (and intensely personal) examination of what art requires, both physically and emotionally, and questions whether it’s worth the sacrifice.

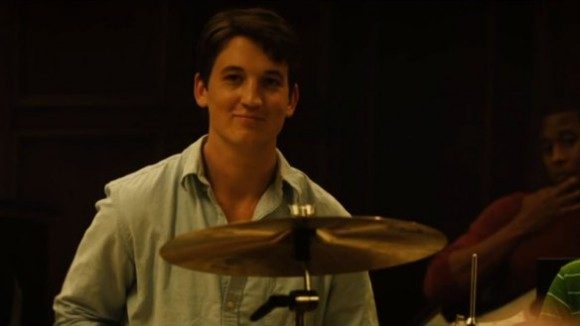

There have been plenty of stories that have focused on the toils of the burgeoning artist – think The Red Shoes, Black Swan, and countless others – yet Chazelle presents the gritty reality of Whiplash with clarity and unassuming grace. Set in the world of jazz, there’s no wistful, “Let’s put a show!” cheeriness or Glee-like celebration of prodigious talent. By refusing to give in to inspiring summations of the uplifting power of art, Chazelle observes the process with a clear, often brutal honesty. Budding drummer Andrew Neyman (Miles Teller), just 19-years-old and new to the Shaffer Conservatory of Music, hardens almost instantly upon realizing just how cutthroat and competitive his new surroundings really are. Being merely good simply isn’t enough, and Fletcher makes sure Andrew learns the lesson when he picks the naive wannabe for a spot on his elite studio band.

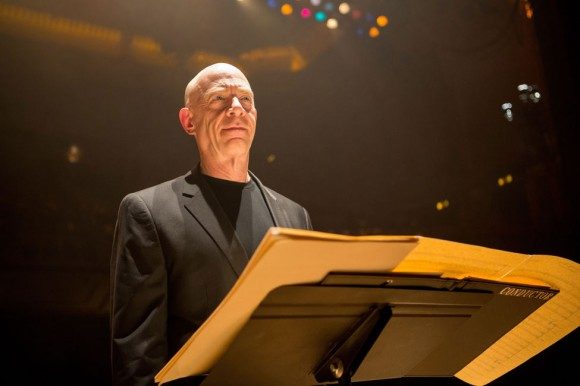

Andrew fancies himself the next Buddy Rich, and wants for nothing but to escape the also-ran status of his father (Paul Rieser), a failed writer. While focused, determined, and eager to impress, Andrew is still somewhat a dreamer, drifting down the road to greatness in a sort of optimistic fog. Fletcher, imposing and demanding, sees himself as the lighthouse attempting to guide promising students like Andrew away from the rocks of a “good enough” society, and he believes any tactic to do so is justified. With that, Fletcher howls and shrieks, shouts homophobic vitriol, even throws chairs and cymbals at his shell-shocked students. Pitched somewhere between John Houseman’s Charles Kinsfield in The Paper Chase and R. Lee Ermey’s Sgt. Hartman in Full Metal Jacket, Fletcher is both the smartest and cruelest man in the room.

While Simmons has impressed before (most notably as a Jason Reitman reparatory player – the actor has appeared in all six of the director’s films – but also for his acclaimed performance in gritty HBO prison drama Oz), his performance in Whiplash could realistically be viewed as the definitive character study from the celebrated character actor. Fletcher is loud and brash, yet subtlety shaded with undercurrents of regret, self-loathing, and possibly even ultra-repressed compassion. While Chazelle’s screenplay never goes beneath the surface of Fletcher’s biting tongue and barbed verbal attacks, Simmons mines currents of desperation and longing that, while fleeting, mark Fletcher a doomed and even pitiable soul as he howls with near surgical precision. Simmons played the same role in the short film Whiplash is based upon, a film that won Chazelle a short film jury prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival. (For a sense of cosmic synchronicity Chazelle won both the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award at Sundance this year.)

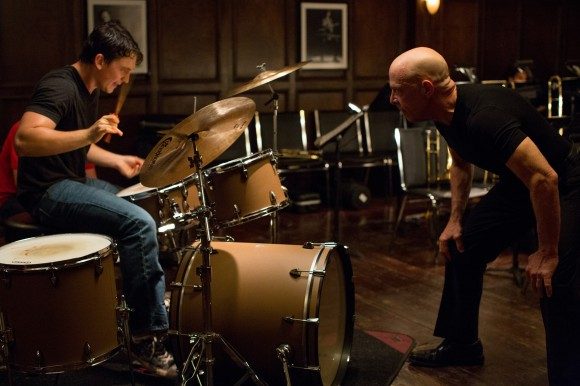

It would be easy to brand Fletcher a villain, and in the film’s wobbliest sections it does just that. But what makes Whiplash a potent case study is the exploration of Fletcher’s relationship with Andrew. There’s something sacred, something shared (perhaps even latently sexual) between the two as the film evolves into a series of psychological mind games. Fletcher, of course, at first has the upper hand, baiting and tormenting Andrew within inches of his sanity – first on the brink of tears after public ridicule, later with never-ending practice sessions rendering his hands throbbing and bloody as his place in the band threatened. Yet there’s a method to his madness, as evident in Fletcher’s oft-recited backstage story of how celebrated jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker only really became “Bird” after Jo Jones nearly decapitated the musician after a poor performance. The theory is that a hunger for greatness can only come from adversity.

Yet Andrew is capable of his own brand of cruelty as well. Teller presents a maturity and quietly unhinged focus as Andrew, making good on his early promise from roles in films like Rabbit Hole and The Spectacular Now and giving a persuasive and committed performance throughout. At the beginning he imbues Andrew with a puppy-dog charm, but as the film progresses, the Teller skillfully strips it away. It’s most evident as he develops a relationship with Nicole (Glee‘s Melissa Benoist), a sweet college student who works a concessionist at a local movie theater. Just after being selected to join Fletcher’s elite band, Andrew summons the courage to ask Nicole out on a date, yet as Andrew progresses through the program, becoming simultaneously more defeated and more entitled, he cuttingly ends the courtship for the good of his art (the scene has hints of the opening segment of David Fincher’s The Social Network). It works a totem of Andrew’s ruthlessness, at once a reaction to, a reflection of, and an inspiration by Fletcher’s teachings. Andrew is really just the flipped side of the same coin as Fletcher himself. Nicole stands as the only female character of note in Whiplash, either of incidental design or a commentary on the boys club dynamics of the conservatory – an early scene where Fletcher is seeking out talent is particularly notable when a female band member is dismissed for merely being “cute.”

It’s in the relationship between Andrew and Fletcher that Whiplash taps into something deep and primal, and only when Chazelle tries to slip too much plot into his delicate study of behavior does the film start to falter. There’s a few implausible bits of happenstance and convenience, and one mid-section segment that leans towards the melodramatic, but the performances never falter and nearly all quibbles are justly put aside when Whiplash nears its rousing and exceedingly confident finale, one of the strongest and most potent of any film so far this year.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

This is Simmons’s show and he hurls everything he has at the screen (and plenty as his frightened students as well) in a bravura performance, yet Whiplash is accomplished in its own right, thanks to the confidence and intelligence of Chazelle’s insightful and crisp direction. The film clearly takes place in a world that the writer/director knows well (Chazelle studied the drums in his youth) and proves an absorbing and challenging pieces of filmmaking. I look forward to see what he will do for an encore.