Here’s a challenge that I sometimes encounter when it comes to discussing movies: how does one go about recommending something that is truly surprising? If something catches you completely off-guard, if part of what makes it so amazing is, in fact, that there was no expectation of excellence around it, how do you recommend it to others? Imagine stumbling onto, say, Vertigo without ever having heard of it or its creator’s titanic reputation. What would an experience like that do to you? And how do you let other people in on it without blunting the impact?

I first crossed paths with Otto Preminger’s steamroller, errr, I mean, movie Bunny Lake is Missing during a class in college. The professor for that particular class was brilliant but also, in her own words, very tricky, and we’d already learned the hard way that she was not above showing us a bad film just to illustrate an academic point. When we filed in and learned that the film du jour was an under-seen late period Preminger that none of us had ever even heard about, a sense of doom quickly settled over the room. As the light went down, I could feel uneasy glances being exchanged all throughout the auditorium. 107 minutes later, when the lights came up, I instead counted the stunned hanging jaws that dotted the audience. One of my classmates described the experience as being “collectively struck by lightning.” What the hell had that been? Where had that come from? How had it been so good?

So you see my dilemma in writing this article. I want to persuade as many of you as possible to watch this film, but I want to give away as little of its voltage as possible. Here’s what we’re going to do: if you are at all open to an adventure, stop reading right now. Just skip the rest of this article, don’t look up what this movie’s about, don’t read any reviews, just go to the iTunes store (see right below the article) or Amazon or wherever you get your movies and watch it. But if you don’t mind a slightly lessened impact and want to find out a bit more about just why this movie is so great (although don’t worry, I won’t divulge any major spoilers), then stick around.

Otto Preminger is one of the towering masters of classical Hollywood cinema that are starting to be less well known than they should be. Part of the wave of Germanic talent that immigrated to Hollywood in the 1930’s, Preminger became one of the premiere directors of the 1940’s and 1950’s. Today he is perhaps best remembered for pulpy noirs like Laura or Angel Face, but he tackled everything from comedies and musicals to courtroom dramas.

Preminger was a huge personality, one of the best-known directors of his time, and was primarily notorious for three things. The first was his temper, with several of his collaborators calling him everything from bullying to tyrannical (and in an industry that dealt with the likes of John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock with aplomb, that’s saying a lot). The second was his tendency to tackle controversial subject matters, being one of the first directors to make films that openly addressed topics like rape (Anatomy of a Murder), drug addiction (The Man with the Golden Arm), Church hierarchy and corruption (The Cardinal), and homosexuality (Advise and Consent). He clashed with censorship boards for most of his career, and was responsible for several landmarks that moved us away from the Production Code. And, perhaps most notably, he was notorious for his very particular style of filmmaking, one that tended to keep the audience separate and detached from the characters. His films tend to eschew putting you in the shoes of any one character, instead asking you to watch everyone’s clashing perspectives and develop your own point of view. It’s a very restrained and subtle way of telling a story and, while it might sound cold or indifferent, it created extremely engaging cinema, particularly in his films about court cases, police investigations, and searches for an elusive sense of what had really happened in a confusing or complicated situation. He was someone who was adamantly set on making films his way, and if not all his films are immortal classics, it’s largely because he was always on the cutting edge.

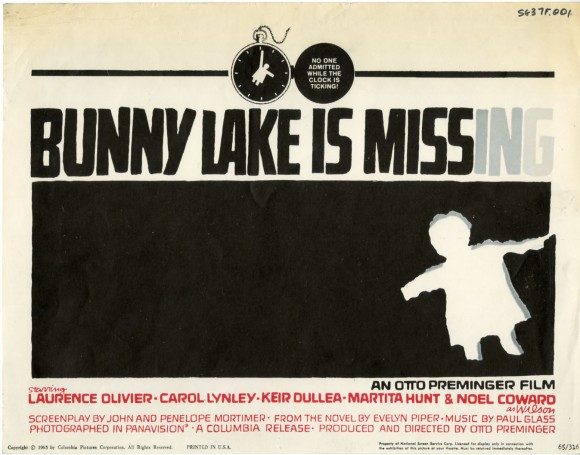

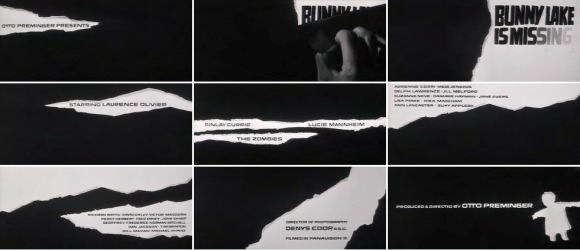

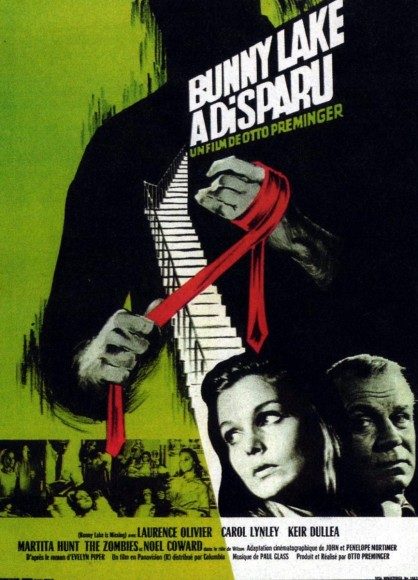

Which brings us to 1965, the year that Bunny Lake is Missing was released. By that point, the heyday of Preminger’s career was behind him. He’d made the classics that his reputation is built on, but had recently been plagued by more difficult and poorly received productions. He made Bunny Lake very quickly, shooting in England and partially financing the movie by cutting a promotional tie-in deal with rising music act The Zombies, who feature at various points in the film. The film performed well in England but didn’t sell many tickets at the American market, Preminger moved to other projects, and something truly special fell through the cracks.

So what’s the story? American Ann Lake (Carol Lynley) has just arrived at her new home in London with her brother Stephen (Keir Dullea a few years before his career-defining faceoff with HAL 9000) and her 4 year-old daughter, the titular Bunny. Running a bit late to meet the movers who are delivering her possessions at their new home, Ann drops Bunny off at the local primary school, leaving her in the care of the only school worker she can find, the cook. When she returns a few hours later to pick up her daughter she finds that the cook has quit after an altercation and none of the teachers seem to be able to find Bunny. Even worse, none of them seem to remember having seen the child at all.

Soon the police get involved, and the investigation, led by a gloriously understated and stiff-upper-lipped Laurence Olivier, is underway to find out what happened to Bunny. It’s not long before a colorful cast of suspects is assembled for interrogation, ranging from an eccentric woman (Martita Hunt) who lives above the school and conducts research on children’s nightmares to the Lakes’ new landlord (theater legend Noel Coward), an aging actor who seems obsessed with exploring as many obscure vices as he can possibly conceive of. Each suspect seems just creepy enough to be a possible perpetrator, but the murky blanks that surround them keep you guessing about just who might be behind the disappearance.

And then things get… weird. Ann returns home only to discover that all of Bunny’s things have mysteriously vanished into thin air, leaving no trace of their existence behind. As the police listen to her story you rack your memory of the earlier scenes at the apartment – did we ever see the child’s possessions? Then there are subtle mentions of past impropriety in Ann and Stephen’s relationship with each other, as well as some slight indications of a history of mental problems in the family. When Olivier’s inspector uncovers the fact that in their youth Ann and Stephen were very invested in an imaginary friend of Ann’s, an imaginary friend who was named Bunny no less, a new question starts to race through your mind:

Did we ever see Bunny during the film’s opening scene? Was she really there? Is Bunny Lake really missing, or is something more complicated, something more disturbing afoot?

For many modern filmgoers, the basic premise of Bunny Lake is Missing is most readily comparable to 2005’s Flight Plan, a Jodi Foster thriller about a woman who boarded a flight with her 6 year-old daughter, dozed off, and awakened to find no trace of her daughter and no evidence that the child was ever even on the flight. What separates the two films, and what makes the older one so much more powerful, is a matter of perspective. Flight Plan keeps us so thoroughly cemented in Jodie Foster’s perspective, and on her side emotionally, that we never really doubt the existence of her daughter. From the start you feel the fingertips of conspiracy around the plot, and you just wait for the puzzle to play out.

Bunny Lake never lets you get that comfortably settled into the camp of any one character, and that makes its mind games all the more unnerving. It’s vintage Preminger, and you can’t escape the sense that no one except him could have made this. It’s a film that stacks up arguments slowly and patiently, both trusting you to remember things that it’s shown you and knowing that key details can and will slip past you. The first two thirds of the film aren’t based on explosive reveals that upturn the plot – they’re based on noticing that a character misremembers the details of an account they gave earlier, or hearing something that might be a slip up and going, “Waaaaaait a minute…”

In other words, Flight Plan is all about watching the inner drama of a character as she struggles to remember what she saw, while Bunny Lake is Missing is all about your inner drama as you try to remember what you saw. It’s not that a movie like Flight Plan can’t be compelling, but the Bunny Lake type is the rarer, the more complicated, and the more engaging of the two experiences. It’s a fascinating and rich viewing experience, and the sheer volume of uncertainty, tension, and paranoia that the film’s first two-thirds inspire in the viewer would be more than enough for me to heartily recommend the film.

But then you get to the film’s final third. The filmmakers knew that sooner or later they would have to reveal what was really happening in the film (although don’t worry, I am not going to do so here) and that, once they did, they would need to do something different. The slow burn reveal of information and sowing of doubt wouldn’t work once the audience knew what was really happening, and the filmmakers chose to deal with this by having the film go completely crazy. Without spoiling too much about what does happen, once the secret’s out of the bag the film goes from its rigid, Preminger detachment into something much closer to the subjective experience that you’d see in a Roman Polanksi thriller. The film’s look, lighting, shadows, camera angles, soundtrack – it all suddenly shifts gears to thoroughly plunge you into one character’s perspective as she goes through the film’s harrowing climax. The film’s final sequence is a tour-de-force in suspense and impressionistic shock (including one of the creepiest and most unsettling jump scares that I’ve ever seen), and its explosive power is magnified tenfold by the fact that the hour of film leading up to it was so restrained and tightly controlled. It’s a stunning example of the power of contrasting styles, and a truly creative and powerful form of narrative problem solving.

In its own way, it’s not completely shocking that Bunny Lake is Missing is one of the forgotten entries in Otto Preminger’s filmography. For a director who made a name with BIG MOVIES that dealt with topical, and controversial subjects, the creepy story of a mother’s struggle with a disappeared child feels oddly small and pedestrian. But for those who have seen multiple of his films, or just those who are looking for a rich cinematic experience, Bunny Lake is Missing almost feels like the ultimate Preminger films. The first part of it is built on his tradition of detached analysis and investigation, getting you to review and question everything you think you know. The second part turns all of that around, unleashing the Preminger take on the visceral, affecting cinema of the thriller. It’s almost like looking at a photograph and its negative, with each one throwing the other into sharper relief. It may not be as much of a stylistic landmark as Laura, it may not be as important to the development of storytelling freedom as Anatomy of a Murder, but Bunny Lake is Missing is one of a very small number of films to successfully combine both the “cold analysis” and “shock and awe” schools of film style in a way were they don’t only coexist, but actually compliment and enrich one another.