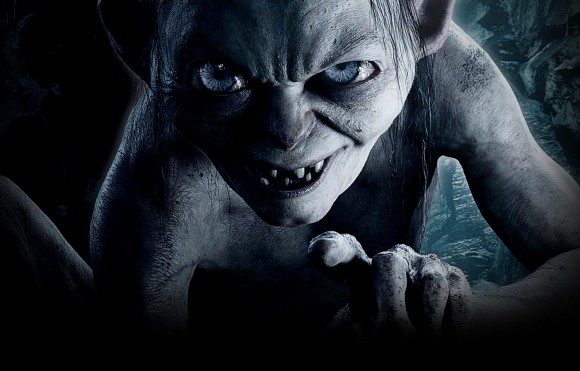

Welcome back to our examination of the motion capture work of Andy Serkis and the impact that it’s having on the modern filmmaking landscape. In yesterday’s post, we went over the case for Andy Serkis being considered the main authorial force behind the computer-generated characters he’s played. Serkis’s performance defines and drives the performance, which is then expertly translated into a digital figure by the expert animators working behind the scenes. They bring the CGI body, he brings the acting, and it’s all one big happy party from there on out, right?

Well… not according to a lot of animators and CGI artists that work with Andy Serkis.

The first big sticking point seems to be the matter of how close to the letter of Serkis’s performances the animation actually stays. Are his motion captured movements really treated as gospel-like dictation, or are they taken more as a set of guidelines and suggestions that are adjusted, calibrated, and, in certain cases, departed from? According to Randall Cook, the animation supervisor and designer for the Rings films, the process of bringing Gollum to life was more of the latter. He writes:

[The scene where] Gollum hears the name Smeagol for the first time in 500 years. We used Andy’s body mocap, but I didn’t care for what I thought was Andy’s too-busy facial performance, so I told Adam Valdez to ignore it and animate something subtler. He animated two shots and Linda Johnson animated the third, and they created a memorable acting moment which did not “honor” Andy’s performance in the slightest. There were many times where we honored Andy’s performance to the letter, but this wasn’t one of ‘em.

One could argue that this is comparable to the performance fine tuning that occurs in most post-production, but changing an actor’s expression does seem to be going a step beyond that. An editor can Frankenstein together a performance out of dozens of takes, but he or she can’t create new raw materials. If every take you have of an actor is too intense, the best you can do with standard tools is minimize the damage by picking the one that is least excessive. But with the animation technology used to create Gollum, animators were able to look at what they had and, for lack of a more refined vocabulary, create a new take. They worked with the director to get into a psychology and define how a character moves and emotes, the kinds of things that are usually limited to actors.

And even putting all of that aside, there’s all kinds of fringe cases that complicate the question of who is most deserving of credit. Even without motion capture, there are characters in animated films that feel like they have a singular, performative author. Every frame of Aladdin that involves the Genie bears the mark of Robin Williams’s handiwork. That’s not because it was made through motion capture, but because so much of the actor’s personality, mannerisms, presence, and improvisation inform what the animators did on the finished film. What about cases where a real-life person was used as a model for an animated character? Shrek’s physicality and movements are rumored to have been largely modeled on French wrestler Maurice Tillet. If that’s true, how much credit should we give to a person who was, in fact, dead before most of Shrek’s creators were even born? The rabbit holes that are involved here can be very, very deep.

The other big question on hand is just how clean cut is the division between performance and the character’s visual appearance? Do these things really operate as independently from one another as Matt Reeves suggests? Not all film make-up is made equal; cosmetics play a much smaller role in the performance that Anthony Hopkins gives in Silence of the Lambs than, say, the one John Hurt gives in The Elephant Man. Yes, the movements and the actions are still carried out by one man, but wouldn’t these things be influenced by the physicality that the make-up would bring to the role? When Chris Walas and Stephan Dupuis won the Oscar for best make-up and hairstyling for their work in David Cronenberg’s The Fly, the made a point of thanking the film’s star, Jeff Goldblum, in their speech, calling him, “the person that made the make-up really work.” Wouldn’t the inverse of this also apply?

The fine folks at Press Play certainly think so. The website, led by founder Matt Zoller Seitz, has long been a proponent of the creation of an Academy Award for “Outstanding Collaborative Performance.” Some roles, they argue, are so intrinsically based on the collaboration between multiple departments that to boil them down to a single, discrete individual’s contributions would be problematically shortsighted at best. These kinds of performances are not, they would argue, a recent phenomenon, and motion capture is simply the latest iteration of something that’s been with us for a long, long time. To back up their claims, they’ve put together stellar video essays on the process and collaborations that went into the realization of Seth Brundle (from The Fly), Yoda, E.T., and, of course, Gollum. These are really outstanding pieces that should be seen by anyone who’s interested in the intricacies of this debate, but if you’re in a rush the gist of it is: there is a long tradition of movie characters that have been awesome precisely because their realization is the work of a large group of people coming together and making creative decisions in a variety of departments collectively, and these roles should be celebrated as such.

So how can we resolve this? How can we properly equip ourselves with ways to interface with these kinds of performances? For our final attempts to find some answers, some balance, and some insight into what the future might bring, join us tomorrow for the final part of our motion capture epic saga.