As anyone who’s ever seen an acceptance speech at the Academy Awards well knows, a great acting performance does not come from just one person. Directors provide guidance and perspective to help ground the performance in the larger whole of the film. Troops of lighting, make-up, wardrobe, and hairstyling specialists carefully calibrate the way a performer looks, down to the smallest details. Editors scour hundreds of hours of footage and assemble a single sequence from many disparate pieces, putting together the perfect line reading from take fourteen with the irresistible wink from take forty-nine. It takes the proverbial village to gather all the pieces. Still, we usually think of the actors themselves as the primary authors of the cinematic performances that we love. Yes, there is a legion of hardworking professionals involved, but we tend to regard them as a support system that works with and around the actors who do the majority of the heavy lifting and deserve the lion’s share of the credit.

This is the prevailing attitude that most of us have when it comes to film acting, and it’s the kind of thing that we never really stop to examine or question. “Of course the actors get most of the credit for a performance. They’re the ones saying the lines, emoting, running around, punching things, etc. Who else would be getting the credit?”

The one place where things get more nuanced is in the world of traditional animation. While voice actors provide an invaluable part of the filmmaking process, the creative input attributed to actors in live action is here shared with animators, designers, illustrators, and other technicians. If a character moves us with his tears in a live action film we think, “What a great performance.” If the same happens in an animated film we might just as easily think, “What incredible animation work.” We tend to think of animated performances, in general, as more of a collaborative creation.

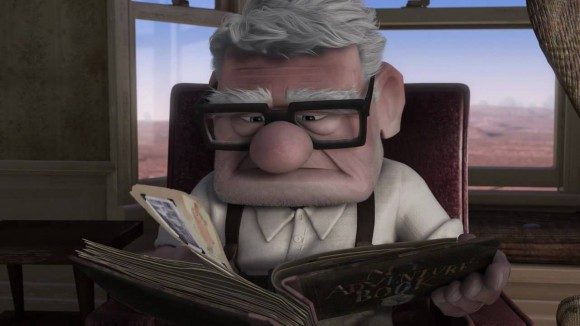

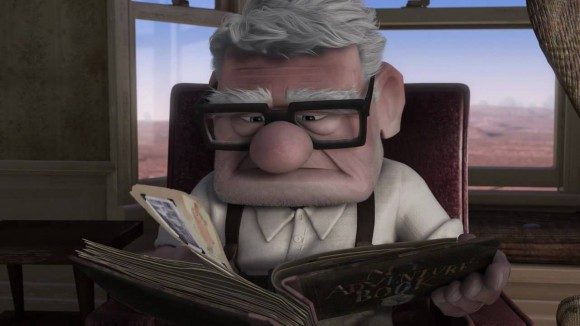

Who gets credit for the “acting” in this moment? Ed Asner provided the voice, but should it go to him or to character modeling artists Paul Aichele and Michael Comet or character supervising animator Thomas Jordan or character art director Albert Lozano or… you get the idea.

Put in other, massively reductive, terms, we still watch Lawrence of Arabia for Peter O’Toole’s performance in a way that we don’t Beauty and the Beast’s for Paige O’Hara’s. For better and for worse, we think of live action performances as having this sense of individual, authorial triumph that is not as present in animation, and few things ever shake us out of this attitude.

And then the world met Andy Serkis.

Born in 1964, British actor Andy Serkis had been working in various theatrical productions, films, and televisions series before his major breakout role as Gollum in the Lord of the Rings film series. Originally hired as a voice actor for a completely computer generated character, Serkis ended up being on the front lines of something much more groundbreaking and line blurring. His character wound up being largely realized by the then very new process of motion capture, a process of tracking a performer’s movements and facial expressions so they can be replicated in a digital character. For a more detailed breakdown of how this technology works, and a brief history of its evolution, click here.

The success of the Rings films, and the massive critical and popular infatuation with the character of Gollum in particular, thrust both motion capture and Serkis into public awareness in a major way. Serkis followed it up with mo-cap work on King Kong, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, The Adventures of Tin-Tin, The Hobbit, and the recently unleashed Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. All of that, along with consulting work on Gareth Edwards’s Godzilla and commitments to direct to fully mo-capped versions of The Jungle Book and Animal Farm, has made Serkis a sort of motion capture evangelical and patron saint of its performers. Few were surprised by recent announcements that he and his unique acting toolkit have been enlisted for both The Avengers: Age of Ultron and the upcoming Star Wars episode.

In all this, Serkis has wreaked havoc with our little performance credit binary. Since the days of The Two Towers’s theatrical run, audiences, critics, and awards-giving conglomerates have struggled to find an appropriate way to recognize Serkis’s unique performances. Should he be eligible for, say, recognition from the Oscars, an entity that has never rewarded voice acting? Can we actually say that we’re watching Andy Serkis’s performance if none of his physical presence on the set is directly visible on the film? Can we really talk about Andy Serkis as the main author of these performances?

“Yes!” say a lot of people, including Mr. Serkis himself. And to hear the reasons why, join us again tomorrow, for part two of our series on motion capture and its place in modern film discussion.