I visited Toronto this past Memorial Day weekend and had a lovely conversation with a beautiful woman. (Aren’t good conversations just a little bit better when the other party is easy on the eyes?) We covered numerous topics, but perhaps the most important was a brief exchange of information about her religion and mine. And as I gazed into her cavernous eyes, the color of which my mind has, sadly, already forgotten, my mind danced with the promise of that which would not be.

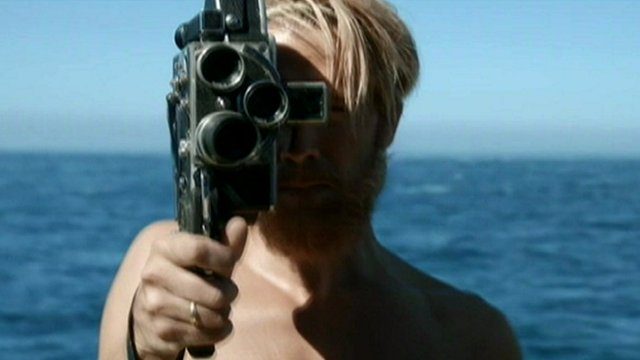

After returning to New Jersey, I sent her an email and she replied with some lovely words and a recommendation for Kon-Tiki, a gorgeous film, albeit not exactly the most surprisingly plotted. It’s the true story of a man and his crew who drifted on a raft from Peru to Polynesia in 1947. It’s an amazing story filled with a host of beautiful visuals, but the most interesting aspect of the film was the adventurer at the center, Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl. The man was hopelessly devoted to a singular idea, that the peoples of South America gathered onto rafts and floated more than 4,000 miles away. His theory was that the ancient South Americans originally populated the islands of Polynesia rather than the peoples of Asia (who were obviously thousands of miles closer).

That unshakable idea was the result of studying a multitude of anthropologic characteristics in Polynesia and a bit of reasoning and logic, but at the end of the day it came down to one simple thing – faith. He believed in the idea, he believed in the natives’ god, and he believed in the strength of the raft, named Kon-Tiki after the god, to withstand the mighty ocean. We say “simple,” but that almost demeans his thought process into being something that can happen overnight or be flipped like a light switch on and off. No, his belief was something that burned inside his soul. It was something that incinerated all doubt and reasoning that could be provided to a modern man.

I grew up with two parents who had left their religions behind in their childhood homes. Neither my mother nor my father place much credence on celestial bodies or spirituality, and I’ve certainly taken after their example. And although we haven’t willingly been inside a church (for my father) or a synagogue (for my mother) in, well… ever, we still stand resolutely behind our own religion.

Science.

Where others put their faith in Christianity or Islam or Judaism or Buddhism or whatever, we use science as a tool to keep from tripping down into the cataclysmic abyss that all humans balance upon. We teeter back and forth on the lip, sometimes chancing a look over the edge into the black vacuum, but we always pull back because we have something that compels us not to jump. We have something that keeps us waking up in the morning and trying to understand our place in the great big petri dish of it all. Man needs something–anything–to believe in because Life is too much to comprehend.

This isn’t in the slightest an attack on religion or even an argument for science. I simply put my faith in science because that’s all I have. It is my religion. How could I sit here and think someone else is “wrong” when I can’t possibly know if I am right?

To be more technical, I would probably label myself as an Agonistic seeing as I live my life under the assumption the universe is expanding rapidly, constantly, and without any assistance from a higher power, but, of course, I could be entirely wrong. Seeing as there is no way, empirical or otherwise, to prove or disprove the existence of some sort of spiritual being, I can only pick the path I have been shown and try not to get too bogged down with my more avant-garde existentialist thoughts. And certainly, if I die and find out that there is a higher power fiddling His fingers above us all, I happen to believe He will give me a pass anyway. Would He really damn the world to Hell because so many of us were ignorant of His existence? That seems like a bit of an asshole move, but we are talking about the guy who (allegedly) brought the flood to wipe out the world, so maybe God’s tendencies do fall more on the blood and sacrifice side of the scale of justice.

The moment when you realize Thor left behind his hot Norwegian wife so he could live on a raft with five other guys…

In any case, Thor the adventurer makes for a fascinating figure because of his blinding faith in his theory. The other five members of his crew willingly followed him onto this raft, and, in doing so, granted him and his idea a greater power than their own rational logic. Based on the information that Thor and the rest of his crew had, it wasn’t rational for them to undertake this journey. Not only did the quest take them thousands of miles across open, shark infested waters, but they had essentially no way to control their raft, no hope to be rescued should they need it, and they were being led by a man who could not swim.

The crew did not believe in the god, Kon-Tiki; they believed in something they could hold and feel and speak to. They believed in Thor.

Now, sure, Thor had done his research and understood ocean currents and had been working on his theory for many years, but still, it is interesting to look back at these five men who heard the entire scientific world telling them Thor was wrong, and they still joined the expedition. They believed in Thor more than every other expert on the planet.

Is this the kind of power that Jesus held over his disciples? Or Muhammad? Or Moses? Or any other prophet? Is this the kind of power that causes grown men to swear their allegiance and willingly give their lives? Is this the kind of power that inspires war? Is this the kind of power that could inspire peace?

I don’t have the answers. I don’t even know if I have some of the answers. All I have is my religion and a willingness to learn more about what is happening around me. In this fragmented world of hostilities and suspicions and confusions, perhaps that could be a good place to start for everyone.

More from Dominick at dominickjgrillo.com or holla at him on Twitter @dominickjgrillo