Spoilers may not be as bad as you think they are. In fact, they might even be… a good thing.

For most film lovers, the above statement is anathema. It’s like saying, “I don’t think Jesus was all that important,” or, “Fascism’s not that bad when you think about it,” or, “Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is totally the best Indiana Jones film.” Unless you’re looking to start a bar fight, you just don’t say these things in public.

Okay, so that may be a bit of an exaggeration, but most film lovers genuinely despise the idea of learning detailed information about a film’s plot or ending before they actually watch the film in question. Just as the name suggests, there is a general consensus that this foreknowledge spoils some of the enjoyment of the film viewing experience. Many film viewers jealously guard their ability to go into a film “clean” and may even react violently if they are made aware of the film’s secrets. I mean, just imagine how angry you’d be if all of a sudden I just blurted out that the killer in [CENSORED] was [CENSORED] and not [CENSORED]? Or that the [CENSORED] in [CENSORED] was [CENSORED] all along? You’d probably find a way to reach through your computer screen and throttle me!

Just think… the makers of this and other similar images might have been doing us all a massive favor all this time.

Now, I love watching a film spoiler-free. I love being surprised by a sudden turn. I love the sinking moment in my stomach when everything snaps into place and I realize what is really going on. I’m not here to advocate the death of the spoiler-free model of film viewing. (For that, you’ll want to head this way.) But in the modern age of Wikipedia, TV Tropes, and social media, it sometimes feels harder to avoid spoilers than it is to obtain them. It may be worth taking a moment to ask if there isn’t something that is gained in exchange for the enjoyment that spoilers allegedly take away from a film.

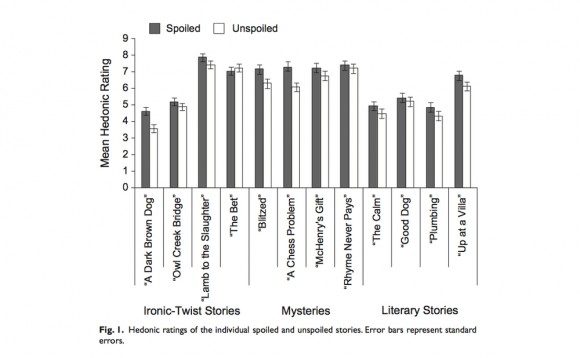

The notion of going into films and other forms of fiction with in-depth knowledge of their plots is controversial but not without it’s supporters. Perhaps its most famous modern advocates are Jonathan D. Leavitt and Nicholas J.S. Christenfeld from the University of California, San Diego. In 2011, they published the results of an experiment in which they had 819 subjects read a group of short stories and rank their enjoyment of the stories from 1 to 10. For some stories the subjects were given a short paragraph describing the outcome of the tale, while others were presented in their “pure” form. Which stories were spoiled and which weren’t was flipped from person to person (so Candidate A would get Story 1 spoiled and not Story 2, while Candidate B would get them the other way around) and the resulting rankings compared. For more details on the particulars straight from the horse’s mouth, click here.

The results were that across the board, subjects who had knowledge of how the stories would end rated their enjoyment of the stories significantly higher than their unspoiled counterparts. This was true for all of the different kinds of stories the experiment tested, even ones that centered on a mystery or had a crazy twist ending. What could possibly account for this?

One possibility is that by knowing what’s coming, the subjects had a greater sense of suspense thrust upon them. Picture this: You sit down and watch a film. It starts with a man in his bedroom. He’s gradually getting out of bed, stretching, looking at his phone, checking his email, et cetera. The film very slowly takes you through this man’s completely mundane morning routine. And then, around minute eight of this, just as you’re starting to nod off, the man opens his closet and a crazy axe-wielding maniac jumps out and cuts our protagonist’s head off! You’d be in shock, especially with such a stark contrast between the humdrum build up and the outlandish payoff.

Now, imagine that right before you start watching this cinematic masterpiece someone tells you that there is a homicidal axe-wielder in the closet. Your viewing experience would be radically different. What before was a long stretch of meandering is now unbearably tense. “Oh God, when will he look in the closet? How long before he looks in the closet? Don’t open the closet!” It’s true that when the murderer finally strikes you probably won’t jump as high as you did in the unspoiled version, but the upside is that you are fully engaged for all of the build-up while in the other version it put you to sleep.

Having some information about what a film’s end point will be can help to get our brains engaged in a more active capacity. If we know that we’re starting at A and ending up at Z, as we watch the interim we’re constantly connecting dots and filling in blanks and there is definitely an intellectual, puzzle-solving pleasure to be had in that. This is such an effective technique of involving the viewer that some films even come with a built-in spoiler. Just think about how many times we see movies that show a scene, or even just a quick flash or tease, of the plot’s aftermath only to then flashback and spend the entire movie building up to that point. For example, we learn that the protagonist of Sunset Blvd. dies at the end of the story in the very first scene of the film and spend the rest of the film actively wondering how we’re going to get from where we are to the inescapable conclusion that’s waiting for us.

The opening scene of Sunset Blvd. Pictured floating lifelessly: our protagonist. I wonder if this movie has a happy ending…

Spoilers enable us to have this kind of experience with all films, even those that aren’t specifically built this way. Say there’s a hypothetical, non-specific film about ghosts, and in its final scene we learn that the protagonist has actually been dead the whole time. If we go into the movie with that knowledge, we don’t get the jaw-dropping, stream-of-profanity-causing surprise at the end, but what we do get is a constant process of deductive reasoning. In every scene leading up to the revelation we are aware of the full implications and nuances of the way the protagonist is interacting with the world, and we are able to grasp a layer that isn’t immediately apparent. We are constantly inferring meaning by combining what the film is giving us with what we know, and there is something undeniably satisfying about that.

But what happens if we don’t just get some information? What if instead of telling you how the ghost story ends I give you a 56-page treatment which details with excruciating depth exactly what happens in every scene of that movie? You wouldn’t really have much to wonder about or deduce, so you wouldn’t get all that much suspense out of watching the film after such a thorough spoiler.

The value of such an extreme spoiler is that they might be able to change what we get out of a film. Conventional wisdom says that all the elements of a film are there to further the needs of the story. Cinematography, editing, acting, set design, and the other crafts that go into the film are all there to impress upon us a sequence of events, a character arc, some kind of ideological message, or some form of content. But if we come into the film already aware of all the intricacies of its plot, if we don’t need to worry about following a story or keeping track of characters, we can focus on appreciating the way shots are set up and arranged, or the details of the color design, or other formal concerns. Spoilers let us dispense with the pretense that gets us into a movie theater and allow us to focus on the craft of the filmmaking. In other words, if we already know the story we start paying attention to the telling.

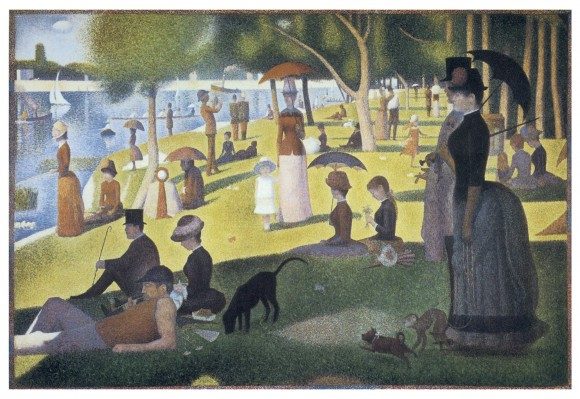

Imagine, for example, that you’re looking at Georges Seurat’s famous painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte. Are you viewing it to glean some knowledge of what 19th Century French park life was like? You might be – but chances are you aren’t. Most people who look at this artwork focus on its miniature, dot-like brushstrokes, or the unique way in which it plays with color optics. Viewers look at the painting as a display of its creator’s artistic prowess, the content it depicts only there to give it substance. Content in service of form, and not the other way around. Spoilers allow us to experience film in this way.

“Hold on,” I hear some of you already saying, “Paintings are a visual art form while films are a narrative art form. They’re apples and oranges.” And to that I say, well… they don’t have to be. That’s the point – we can look at films and focus on their use of form, color, light, sound, and acting simply for the sheer craft and skill that is involved in them. Experimental filmmakers like Stan Brakhage have tried to illustrate this by making films with little or no discernible narrative, but we can just as easily subvert traditional expectations by frontloading ourselves with all the spoilers we can find about the film’s plot. If there’s nothing that we can possibly learn from what’s happening, all that’s left to engage us is its presentation. This is the great gift of the age of the spoiler: the ability to choose what we want the priorities of our first viewing of a film to be. Do we want the surprise of discovery, the intellectual suspense of puzzle-solving, or the tactile appreciation of formal awareness?

Now, does this mean that you should rush to your nearest rooftop and start shouting the endings of every film you’ve ever seen? Absolutely not. The point to all of this is that there’s no ideal or superior way to watch films, each method has merit and no one is doing it wrong. It’s all about what each viewer wants out of his engagement with the medium. As soon as we start policing the way people watch films, either for or against spoilers, we are limiting the medium. Spoilers are not the work of the devil. They can make watching a film more engaging and exciting, even add a whole new layer of appreciation to the proceedings, but they will only work that way if they are embraced consciously and deliberately, not if they are forced upon us.