“Can you pull in Leviathan with a fishhook or tie down its tongue with rope?” – Job 41:1.

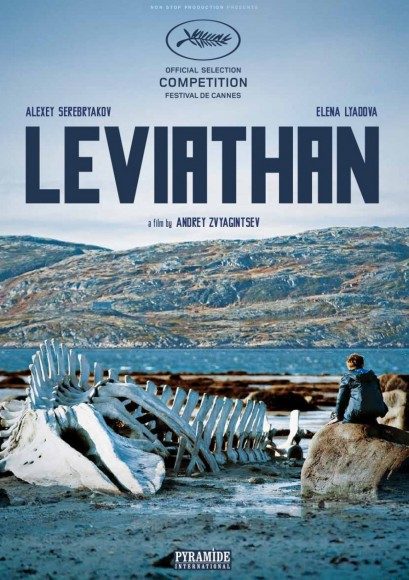

Leviathan is a behemoth of a film. Set in a small Russian town on the jagged coastline of the Barents Sea, this modern retelling of the Book of Job is an intimate tale told on a grand scale. It’s a challenging film, one that requires patience and a certain amount of resilience on the part of the viewer. But for those willing to walk the increasingly bleak road of Leviathan, the journey is profoundly affecting.

The film follows Kolya (Alexey Serebryakov), a mechanic who works out of a small garage next to his remote home on the edge of town. When he is told his house will be demolished, he calls upon his old army friend Dmitriy (Vladimir Vdovichenkov), now an attorney, to help stop the corrupt mayor Vadim (Roman Madyanov) from taking his home. Dmitriy comes prepared to play both within the bound of the law as Kolya’s counsel and by street rules, packing a folder of dirt on Vadim he soon realizes he is ill-equipped to utilize. Dmitriy’s murky motivations are complicated when he begins in affair with Kolya’s apathetic wife Lilya (Elena Lyadova). There are no heroes in Leviathan.

Director Andre Zvyagintsev keeps the plot sparse and allegorical, allowing small movements to take on immense implications. Vadim’s position within the government, the mafia, and the church is chillingly undefined. This is a world where the line between the government and the mafia isn’t just blurred, it’s non-existent. The repossession of Kolya’s home leaves him bare to these unyielding forces. Zvyagintsev, who co-wrote the film with Oleg Negin (Elena), keeps the lens unflinchingly on Kolya, but his problems never feel singular. Dmitriy suggests he move to Moscow, but this beast which pursues Kolya is not one confined to his small, unnamed town, and Vadim is merely a cog within a much larger machine. One of the film’s lighter moments involves a shooting trip using the portraits of Russian leaders going back to Lenin. Kolya asks if they’ve got anyone more current; someone responds that “it’s too early for the current ones; we need more historical perspective.” And yet it’s impossible to miss the portrait of Putin that hangs above Vadim’s desk.

Despite these political musings, Leviathan is not a political film. It’s not even really a plot-driven one; most of the major plot points occur within the first 45 minutes. Zvyagintsev has crafted a film of contemplation, giving the characters room to breathe, knowing their next step will have grim consequences no matter what direction they take it in. Leviathan understands that true tragedy is something that happens incrementally and lets us watch as the characters destroy themselves and each other.

If Leviathan is anything, it’s a morality tales, but one of the tallest and most complicated order. The film dismisses any notions of heroism of villainy, eschewing them for a world that is as complex as it is bleakly realistic. Kolya’s fate is not is not rooted in some inherent character flaw, and yet he remains almost wholly responsible for it. Conversely, Vadim is depicted as a man of both brash braggadocio and wretched cowardice. Vadim justifies his treatment of Kolya because he views him as an insect. The austere truth of Leviathan is that he is right.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

Leviathan might buckle under its own weight from time to time, but it’s still a ride worth taking. Zvyagintsev’s modern retelling of the Book of Job is biblical in every sense of the word. In many ways the film serves as an indictment on the corruption of modern Russia, but it transcends contemporary politics, achieving a level of parabolic universality. The performances are excellent all around, suitably understated and raw. Cinematographer Mikhail Krichman creates beautiful and imposing landscapes out of the Russian countryside. Leviathan might be bleak and fatalistic, but it’s also a film of great profundity and beauty.