Today we’re going to talk about one of the fringe sectors of cinema: stop-motion animation. Stop-motion has been around, in one-way or another, for pretty much all of the history of cinema. It’s been responsible for everything from visual effect showpieces and fantastic creatures to full length-features. Even though it’s never been the world’s most popular form of filmmaking, it’s always had an audience and avid followers. In recent years, thanks to the explosion of digital media and the proliferation of DIY indie animators, it’s actually become the center of one of the most popular underground and grassroots filmmaking scenes. With the release of Laika Studio’s The Boxtrolls, which purely from a technical standpoint might be the most ambitious stop-motion project ever undertaken, just a few days away, it seemed like a good moment to talk about this art form and why it holds such a strong sway over so many of us.

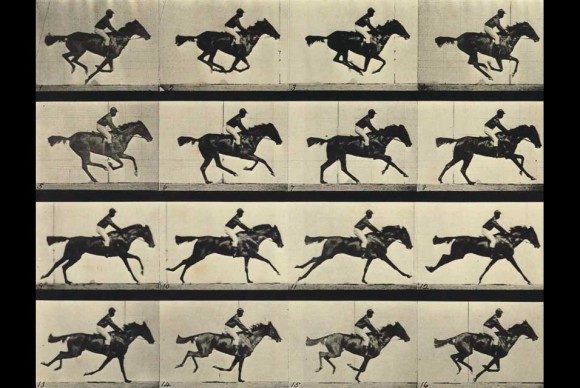

First, however, a little context on what we’re discussing. Stop motion is a discipline that combines parts and pieces from many different sectors of filmmaking. Live-action filmmaking is accomplished by taking a large number of pictures of an object as it moves. When those pictures are projected in sequence at a speed that is faster than what the human eye can fully register, we get the illusion of movement. If instead of photographing a moving object you shoot pictures of a series of very similar (but slightly different) illustrated images, you can create the impression of a single, moving drawing. That’s traditional 2D animation, and, because you need to create and photograph individual drawings, each of which only makes up a fraction of a second of motion, it’s an extremely time-consuming process.

When instead of taking individual photographs of drawings, you start taking photographs of an inanimate object, say a puppet, and making slight adjustments to its positioning between each shot, you can create the illusion that the object in question is moving. This is the essence of what we call stop-motion animation, an umbrella term that encompasses many subsets, like Claymation, Pixilation, and Puppet Animation. Fifty years ago, most cinema-goers might have known it as the process that made the dinosaur and ape effects in King Kong possible, or what brought us the amazing creatures from Ray Harryhausen’s films. For a younger generation of film-lovers, the main reference point would probably be Henry Selick’s fantasy The Nightmare Before Christmas.

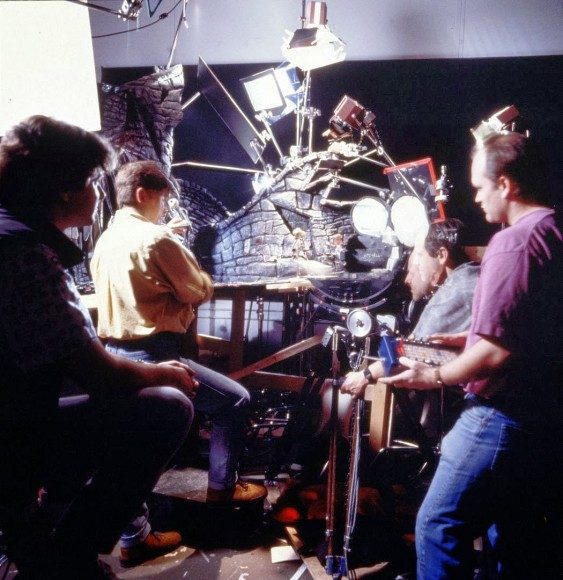

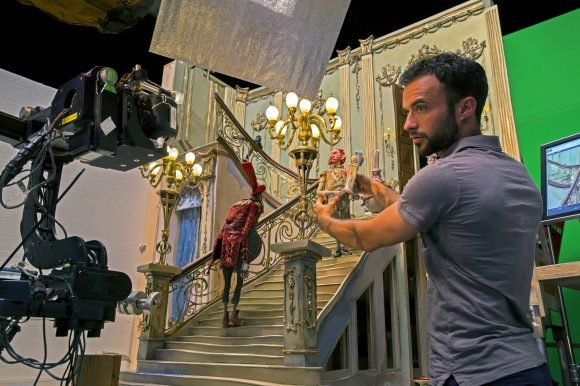

One of the first things that a lot of people notice when discussing stop motion animation is the fact that it seems to bring together a lot of the challenges of live action and 2D animation. Unlike traditional animation, in which about the only limit is what an artist can think to draw, stop-motion actually needs to be realized in a physical location. You need to be able to physically create whatever it is that you’re animating, which means that you’re still building a set, you’re still lighting every shot, and you’re still bound by the limitations of what you can do within your space. But on the other hand, you don’t get the ease of simply recording motion in real time – you still need to go fraction of a second by fraction of a second. Work that might take a few minutes to capture on a live-action set can eat up weeks of your time on a stop-motion one. A cynical person might feel inclined to say that stop-motion animation is just a collection of the most difficult parts of the other filmmaking disciplines. Why in the world would anyone subject themselves to this draconian method?

Well, because for all of its demands and rigors, stop-motion also opens up some interesting doors. Consider, for example, the first three minutes from Aardman Animation’s Wallace and Gromit in The Wrong Trousers. This little sequence, where Gromit gets his master out of bed, dresses him, and serves him breakfast through an elaborate Rube Goldberg-esque machine, is one of the most famous pieces of stop-motion animation, and it’s something that would never work in either live-action or traditional animation. If you tried to do it in real-life, you wouldn’t be able to have Wallace moving so organically and fluidly through the rigid machinery. It would either end up looking fake or too bulky and stutter-y, the plasticity that makes it funny would be gone. If you tried, on the other hand, to do it with 2D animation, it would be a too abstracted and too divorced from anything physical. What makes Aardman’s sequence so engaging is that you feel both the element of unreality but also the fact that it’s all taking place in a continuous space. You need one foot planted in both realms to truly make it work, and that’s what stop-motion animation offers up. It’s an unusual space to conduct business in, but it opens up new possibilities for comedy.

But okay, what if you’re not interested in being funny? What if you’re trying to be subversive, or unnerving, or get under people’s skin with something kind of grotesque? What if you’re looking to do something with regular household objects, something you can’t actually do in real life, but it’s important that those objects look and feel real. 2D animation might work, but again, it might make things feel too abstracted. This is precisely the space where master Czech animator Jan Svankmajer has built his career, and he is one of the most prolific and accomplished users of stop-motion animation. Take a moment to watch one of the installments that he did on the subjects of food and eating. Imagine how lessened the effect of a piece like that would be if you couldn’t identify the things the men were eating as real objects. This kind of animation allows you to insert that wrinkle of the impossible and the disturbing to something that is very grounded in real-world textures.

All right, all right, but what if you’re not interested in doing either one of those things? What if you just want to open up the possibilities of what you can do with a human figure? To play with things like perspective, space, or even gravity, but without having to spend money on visual effects the way Gravity did? This is exactly what Israeli songwriter Oren Lavie accomplished with his music video for Her Morning Elegance. Working with this kind of animation allowed Lavie to move a human figure in innovative ways, opening up different possibilities for graphic experimentation. Best of all, the irregular movement of this style of animation works well with both the rhythm of the song and the dream-like sense of progression the video is trying to create.

This is not to say, however, that all subject matters would benefit from the stop-motion treatment. It definitely has its time and its place, and there are certain places where its use would be to the detriment of what it’s depicting. Imagine what a tortured creature a stop-motion version of the Genie from Aladdin would be, for example. That is a character that thrives on the smoothness and speed that the unbound realm of 2D animation provides; trying to ground it in the physical reality of stop-motion would just serve to blunt his effectiveness. It’s no accident that most of the great stop-motion films fall into one of two categories: comedies that make the mundane entertaining by twisting it just a little bit out of shape (see Wallace and Gromit, or most of Aardman’s productions) or films that focus on fantasy worlds that feel just a little bit more real and scary than they should (see Nightmare Before Christmas, or Coraline and the rest of Laika’s ouvre so far). The main lesson that might be gleaned from all of this is that if the price that stop-motion animation pays is the hard work of two mediums, the payoff it receives is the ability to create something that feels at least vaguely attached to both of them at the same time.

Around the time that he was completing Coraline, director Henry Sellick did an interview for the A.V. Club. His response when asked why he continued to work in stop-motion in the era of CGI is about as perfect a summation of the art form as anyone has ever given.

I’ve done almost all the styles of animation: I was a 2D animator. I’ve done cutout animation. I did a CG short a few years ago. (…) Stop-motion is what I keep coming back to, because it has a primal nature. It can never be perfect. There’s always something like—[Points to the Coraline puppet on the table.] Coraline’s sweater, you can notice here that it’s sort of boiling. And that’s because people are touching it and moving it for every frame. There’s an undeniable reality that I don’t think any of the other mediums give you. You know these things are real even if you don’t know exactly how they move, how big they are.

CG can do anything, but it can’t do everything well. What it naturally can do is special effects. But using stop-motion comes from our desire to do handmade stuff. There are always going to be kids who get out whatever it might be—clay, bits of wire, Barbie dolls, Legos. They want to tell little stories. Almost any modern video camera can take stills, so there’s always this fresh crop of kids that like making things and moving them by hand. So it’s as much our desire to keep it going as what we believe is the public’s desire for handmade stuff that really feels handmade, where they aren’t being tricked into it being handmade. That keeps us going.

Even in the age of CGI, we still want to see handmade stuff. And, perhaps more than that, we still want to see things that don’t exist, which couldn’t ever possibly exist, and which still have an undeniable reality to them.