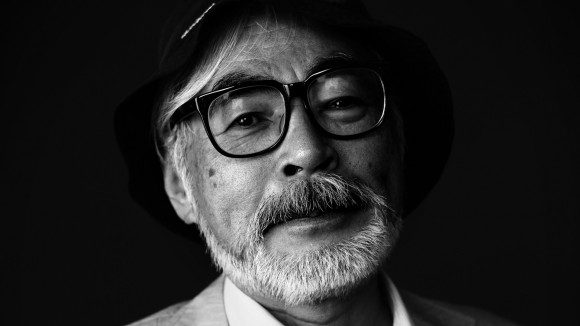

Like all major directors, Hayao Miyazaki has a set of themes and situations that his work keeps revisiting. The epic fantasy of something like Nausicaa of the Valley of the Winds. The gentle coming of age stories of Kiki’s Delivery Service or My Neighbor Totoro. The down-the-rabbit-hole discovery of a magic world seen in Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle. And, of course, the gigantic environmental odyssey of Princess Mononoke. It takes a bit of looking to find a film in the director’s filmography that doesn’t fit into one, or more, of those broad categories.

The other issue with an oeuvre that is as universally well-regarded and respected as Miyazaki’s is that inevitably something truly excellent is going to get lost in the shuffle. When you produce five, six, seven, eight masterpieces in a row, one of them is going to slip through the cracks of public consciousness, one will not be thought of as fondly or as highly as it deserves. And, not coincidentally, that film is also the one that is most unlike the director’s other works, the one that strays the farthest from the trail. So let’s take a moment to dust off the neglected gem and talk about Porco Rosso.

Now, let me be upfront about something: Porco Rosso is admittedly less of a B-Side than the first two films in this feature. Both Stage Fright and Kiss Me, Stupid were box office disappointments and severely reviled by both critics and audiences at the time of their release. Neither Hitchcock nor Wilder was particularly quick to stand up for the merits of those films, with various interviews showing that they considered them the runts of their respective litters.

Porco Rosso went through none of the above. It was well received upon its release, became the highest grossing domestic film in Japan in 1992, and is remembered fondly by its creator, who has for a long time been itching to a get a sequel to the film off the ground. So at the time of its release the film had no trouble engaging with audiences, but over the years it has definitely found itself relegated to the sidelines of the Miyazaki canon. Everyone has seen Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, but when I mention Porco Rosso the typical reply I get is a furrowed brow and a mumbled, “That’s the one with the pig, right?”

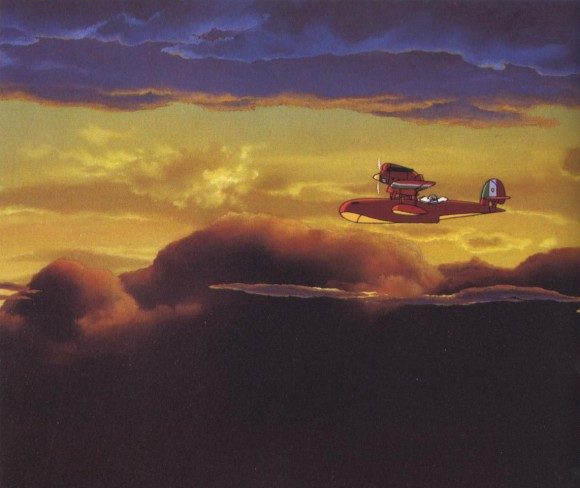

Porco Rosso is set in various small islands of the Adriatic Sea in the years between the two World Wars. Marco Pagot (or Rousolini in the U.S. translations) was a superstar fighter pilot in the Italian Air Force during the Great War, but the rise of Fascism and military dictatorship resulted in him deserting the armed forces and abandoning his country. When the film opens we find him making a modest living as a bounty hunter, hired gun, and full-time crabapple spending most of his time fending off the various pirate gangs that prey on ships in the area. He is the uncontested master of the sky… until a hotshot American pilot by the name of Curtis shows up and beats him at his own game. But Marco is not one to stay down for long, and after acquiring the services of a teen prodigy mechanic by the name of Fio is ready to take back what’s his. Can Marco and Fio beat the pirate gangs, defeat Curtis, and reclaim the aging ace’s honor?

And… okay, fine, there’s one more big-ish thing. Basically… Marco is kind of a pig. And I mean that last sentence in such a literal way that it’s a tiny bit scary. At some point in the past, Marco was put under some kind of curse or spell or something (the film doesn’t really specify) and he now looks like an anthropomorphic pig. He can still talk and communicate and operate planes, and in general his body below the neck seems to be that off a portly human being, but he has the head of a hog.

If it seems like I’m just dropping a major bombshell like that into my description of the film as an afterthought, it’s mostly because that’s how the film treats it. I cannot emphasize enough how much the pig-curse is not the central focus of Porco Rosso. A lot of people tend to get a little put off by the premise, but the central track of the film really is all about Marco’s adventures taking down pirates, his aeronautical rivalry with Curtis, and his relationship with Fio. Everyone in the world seems used to his ailment and no one really blinks an eye at the fact that there’s a pig flying a plane. Marco himself seems very much at peace with his condition, claiming that his current head fits his personality much better than the old one, and never does anything that would qualify as looking for a cure or a way to break the curse. The film is much more about his pigheadedness than it is about the fact that he has been saddled with having a pig’s head.

So why is this such a great movie? Let’s just knock the basics out really quickly: this is a studio Ghibli film made directly under the supervision of the big man himself, so all the usual impeccable craftsmanship that comes with that is present in this film. The animation is without parallel, offering up some of the most fluid and detailed line work you will ever see. The characters are beautifully designed and incredibly expressive. Marco in particular feels like a minor miracle in animation: he spends the entire film wearing a pair of aviator sunglasses, which means we never see his eyes, but the animators find so many creative ways to play with his face and his animal features that he always feels emotionally accessible. Ghibli mainstay composer Joe Hisaishi has yet to produce a bad score, and he does career best work in this film, combining his usual arsenal with some Mediterranean folk influences for an incredibly sweeping and affecting score. As far as the technique that went into it goes, Porco Rosso is faultless.

What makes the film feel so special, and so unlike other films of Miyazaki’s, is the way that it rests between a lot of different worlds. A question that often comes up when evaluating the Ghibli films is the matter of how kid-friendly they are. Is the film aimed at young kids, the way that My Neighbor Totoro is, or is it more mature and demanding, the way Princess Mononoke is? I’ve been debating this issue for quite a while now, and I honestly don’t have much of an answer yet.

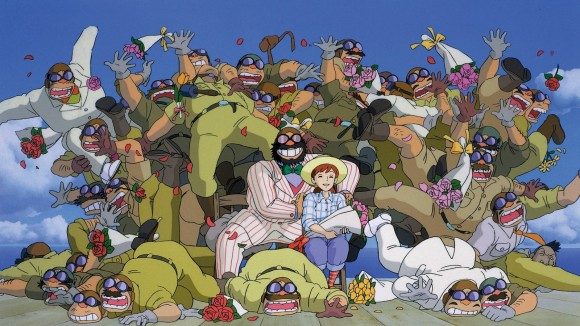

On one hand, the film is definitely accessible to children, and it doesn’t have anything as intense or as violent as the fare you would see in some of the studio’s more adult films. There are constant dogfights throughout, but the carnage is practically non-existent. One of the things we learn about Marco is that he only shoots down planes when he knows that the shot he’s taking won’t harm the other plane’s pilot. Similarly, the story of the film is simple and filled with enough action and hijinks to hold a kid’s interest. Will grumpy old Marco and young, bouncy Fio be able to stop the pirates and beat the bad guy pilot? It’s great, uncomplicated fun.

But, on the other hand, there’s definitely all of this stuff that is happening around the edges of the film that feels like it would fly over kids’ heads. It’s no accident that the film is happening against the backdrop of Fascism and the two World Wars. There is a very sad backstory to Marco, one that is filled with a lot of tragedy and senseless loss, but the film never sits you down to just pound you over the head with it. Instead, you learn about his past slowly and through allusions, putting together a look here with a quiet moment there. There’s a darker, more mature story to be gleaned within the adventure of Porco Rosso, one that comments on the nature of war and which requires a sharp eye to catch.

But then again, I don’t want to make it sound like it’s too dark. By and by, the film is extraordinarily silly, filled with as many comedic sequences as thrilling action scenes. The adversaries in Porco Rosso are particularly funny, some of the greatest comedy villains that you will ever see in or out of animation. The various pirate gangs are bumbling, or cowardly, or petty, or all three, and watching them out-incompetence each other is a constant joy. Even Curtis, who the film does establish as genuine threat due to his skill with an airplane, is such a cartoony egomaniac when he’s on the ground that he never fully goes into the realm of the scary or the menacing. Even if the specters of war and dictatorship are hanging around, the various goofy elements of the film keeps the proceedings light.

But not too light, because the film does have spots of genuine darkness and pathos. One scene that flashes back to a battle during the war in particular is very moving and much harsher than the rest of the film allows itself to be.

And by now you’ve probably realized that I’m caught in this film’s very bizarre loop. It’s impossible to try to describe the experience of watching Porco Rosso without falling into that recursive cycle of, “It’s really kid-friendly but has some things that only adults will catch but it’s okay because it’s really silly but it’s not so silly that it can’t be really dark and moving when the gloves come off,” and so on.

In a lesser movie this kind of shifting nature might be more than the narrative can handle, but Porco Rosso pulls it off, and it ends up being, in many ways, the film’s greatest triumph. A different movie tackling so many different modes of operation might feel a bit schizophrenic or spread too thin, but everything in Porco Rosso is so tightly interwoven and finely tuned that it ends up coming across as an incredible tonal juggling act. Just when you think that things have gotten so goofy that the film couldn’t possibly bring you back into the dour losses of the Great War, just when you think that a ball is about to slip through the fingers, something turns at the drop of a hat and the film makes it through another sharp embankment.

So if Porco Rosso isn’t like any of the big Miyazaki categories, if it isn’t a big fantasy epic, or a whirlwind trip down the rabbit hole, what does Porco Rosso end of being? At the end of the day, more than anything else it feels like an in-depth character study, a psychological portrait of a war veteran and a survivor. It gets there by way of adventure and dogfights and lots of silly comedy, but the main dramatic threads that emerges throughout the film are the questions of “Who is this man?” and “Why does he act this way?” In that regard, Porco Rosso is very similar to the other outlier of Miyazaki’s catalog: his swansong film, The Wind Rises. Both explore the inner thoughts of enigmatic aeronautic geniuses, and both have their roots in the darkness of the two World Wars. They almost feel like mirror images of each other, with The Wind Rises playing the dour tragedy with a glimmer of hope to Porco Rosso’s extravagant comedy with an undercurrent of sadness.